Cities Take Lead on Coronavirus Response At Times, Leading to Friction With States

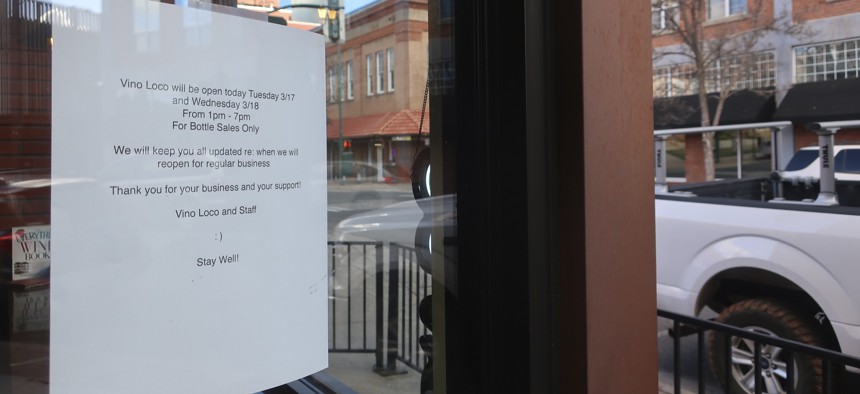

A sign at a wine shop in downtown Flagstaff, Ariz., Tuesday, March 17, 2020, lets customers know the shop will be closed temporarily. The mayor of Flagstaff ordered restrictions on restaurants and the closure of other businesses due to the coronavirus. AP Photo/Felicia Fonseca

Debates over state and local authority could come into play going forward as government leaders decide on how to dial back restrictions and restart the economy.

In the fight against the coronavirus, some city officials acted earlier, or went further, than their state leaders with public health measures meant to curb the spread of the respiratory illness. It’s a dynamic that has at times led to tensions and clashes over whether cities have the power to adopt certain policies under state law.

Mayors in states like Arizona, South Carolina and Mississippi say that when it comes to precautions intended to slow the virus’s spread, like stay-at-home orders and deciding which businesses can remain open, they’d prefer a strong and coordinated approach at the state level.

In fact, some emphasize that they would still like to see more from their state counterparts, saying they lack the resources and authority locally to take needed steps. And, at times, they have felt it necessary to go beyond state policies that they believed were inadequate.

These types of disconnects promise to remain a sore spot in the weeks and months ahead, as states discover whether existing policies are enough to constrain the coronavirus. Frictions could grow even more intense as officials decide how to best unwind the restrictions that they’ve imposed on residents and businesses.

“I’d much rather have had uniformity statewide,” said Mayor Steve Benjamin, of Columbia, South Carolina, as he reflected on how response efforts in the state have played out in recent weeks.

“I want the governor to lead, and lead from the front,” he added. “If he leads, we'll follow. In the absence of that leadership, it is required of us to act. To stand in the gap.”

There have been instances, Benjamin said, where the city “had to kind of go our own way.”

Columbia enacted a stay-at-home order on March 26—about 11 days before Gov. Henry McMaster issued a similar decree. McMaster, like other governors, had adopted a ban on dine-in restaurant service that went into effect on March 18, and on March 13 he had declared a state of emergency due to the coronavirus and ordered schools in two counties closed.

But at the time that Columbia issued its stay-at-home order, Benjamin said he wasn’t satisfied with the state’s response, and that the governor’s actions up to that point were “ineffective at addressing the scale of a growing pandemic.”

“His executive orders or his rhetoric from the podium did not underscore to the people of South Carolina the gravity of the matter,” the mayor added.

McMaster’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment on Monday and Tuesday.

South Carolina isn’t the only place where state and local officials haven’t moved in unison.

In Georgia, local officials in coastal communities earlier this month panned Gov. Brian Kemp's decision to allow people onto beaches as long as beachgoers obeyed “social distancing” guidelines calling for people to keep space between one another.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a stay-at-home order on April 1, but faced criticism for not acting sooner to adopt the statewide measure, leaving a patchwork of inconsistent local restrictions. The New York Times has reported that people who in March attended crowded parties around spring break season in Florida, or who visited Disney World, later fell ill or even died from the virus.

Columbia, for a moment, appeared to be edging towards a legal dispute with the state when the South Carolina attorney general’s office issued an opinion that raised questions about whether state law preempted the city from imposing its stay-at-home order. Charleston had a similar order in place that was also called into doubt.

Benjamin explained that Columbia was prepared to defend its order in state court. “We knew that clearly state law was on our side, as was public health policy and common sense,” he added. Ultimately, he said, state officials did not challenge the city’s directive.

So far, at least 43 states have issued some type of broad order calling for people to shelter-in-place, or for businesses to close.

Notably, McMaster’s “home or work” mandate is written to “supersede and preempt” local measures that conflict with it, a potential check on cities looking to go beyond the state guidelines.

Kim Haddow, director of the Local Solutions Support Center, a group that focuses on issues related to state preemption of local governments, said some of the conflicts over the virus response mark “a new front in a longstanding fight” over state and local authority.

But she also cautioned against looking at these latest instances of state-local disharmony as strictly conflicts between state-level Republicans and Democratic-leaning cities, even though that’s a frame commonly imposed on other examples of preemption. Haddow noted that some GOP governors have taken swift action to combat the virus.

“I do think this is a deeper ideological issue,” she said.

In her view, what’s driving a wedge between some policy makers are different perspectives on how to best balance priorities like individual liberty and community safety, or protecting public health and preserving the economy.

There are other ways that the current situation differs from the familiar preemption battles of recent years, where cities have sought to adopt policies like minimum wage hikes, or plastic bag bans, only to find their efforts overridden and derailed by state laws. Here city leaders are not necessarily eager to flex their muscle and put in place unique or progressive programs at the local level.

“What I’ve really been crying out for is a uniform approach from the state,” said Chokwe Antar Lumumba, the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi. Lumumba noted that, back in mid-March, his city moved before the state did to adopt measures meant to stop the spread of the virus—like closing bars, banning dine-in service at restaurants and restricting group gatherings.

But he described a sense of frustration over how, earlier on in the crisis, people were regularly traveling in and out of the city from neighboring localities that had not taken similar precautions.

“That was problematic, and I spent days trying to reach out to the governor, trying to encourage him to help us establish a uniform policy,” Lumumba said.

Since then, Lumumba and Gov. Tate Reeves have both signed stay-home orders that went into effect on April 3.

But Lumumba said that Jackson now finds itself on its own in other ways. The city has moved ahead purchasing 6,000 of its own virus tests, 5,000 of which will be distributed through a partnership with Jackson-Hinds Comprehensive Health Center. An additional thousand tests will be prioritized to first responders and inmates at a local jail, according to the city.

Jackson is also introducing its own phone hotline and a “symptom tracker” to help identify hotspots across the city for Covid-19, the respiratory illness the virus causes. There are other measures as well, like a deal with a local hotel to provide quarantine housing.

“All this has been done independent of the state,” Lumumba said.

Jackson is Mississippi’s largest city, with about 164,000 residents. But Lumumba said on Saturday that the governor has not been in regular contact with him during the crisis, and that the last time they’d spoken was more than 10 days ago.

“I’ve called him maybe four times and have not been able to get him,” the mayor said.

“We’re on the same page in terms of he has suggested that he won’t get in our way,” Lumumba added of Reeves. “We’re not on the same page in terms of communication and support.”

Renae Eze, a spokesperson for Reeves, said in an emailed statement on Tuesday that the governor and his team had been in regular contact with local elected officials across the state “to ramp up our partnership and coordination throughout this outbreak.”

She also said that the governor’s office had asked the Mississippi Municipal League to set up regular calls for the governor with mayors across the state and that Reeves and Lumumba “have had many direct phone calls” during the Covid-19 response.

“Governor Reeves strongly believes in the principle of ‘state managed, locally executed’ as the best way to ensure the health and well-being of all Mississippians,” Eze said.

“We look forward to continue growing our relationship with local elected officials around our state as we work to combat the spread,” she added.

Meanwhile, in Arizona last month, Flagstaff Mayor Coral Evans’ decision to close nail and hair salons in her city landed her in a dust up with a state legislator, with the lawmaker raising the possibility of trying to withhold state funding over the policy.

Lauren Kuby, the vice mayor of Tempe, Arizona said the episode highlighted the still “looming” questions in her state about whether the governor can preempt cities from taking action that the locality deems necessary for protecting residents during a public health emergency.

“This constitutional issue, it hasn't gone away. It’s in the background,” Kuby added.

For her part, Evans and other Arizona mayors moved faster than the state early in the pandemic, deciding in mid-March to close businesses like bars, gyms and movie theaters and to restrict restaurants to delivery and to-go service.

“I didn't want to do that,” Evans said. “That was not a popular decision.”

“I was trying to take a proactive stance,” she added.

Eventually, Gov. Doug Ducey issued a statewide stay-at-home order, effective March 31—a move that mayors in some of the state’s bigger cities urged him to take. He also clarified that businesses like nail and hair salons, as well as tattoo parlors and spas, would have to close.

Flagstaff is located about 75 miles from the southern entrance to the Grand Canyon National Park, and tourism and outdoor recreation are important parts of the local economy. These sectors are in line to take hard hits due to the virus as people cancel and postpone travel plans.

“The economic impact on my city has been disastrous,” Evans said. But, right now, she said her top priority is public health, even if that means tougher restrictions on businesses and residents in the near term. “It would make more sense to focus on preserving people's lives and getting to the end of this sooner,” she said. “So we can get back to fixing our economy.”

When it comes to Arizona’s current statewide policy for businesses during the outbreak, Evans said she still has some concerns—for example, golf courses have remained open, and she believes there could be better standards for protecting shoppers and workers at grocery stores.

But she said it’s pretty clear that the governor’s orders do not leave leeway for mayors to impose precautionary restrictions that go beyond those that the state has prescribed. “From my standpoint, as mayor, I feel like I've done as much as I can legally,” Evans said.

Ducey’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment on Monday and Tuesday.

Lumumba, the Jackson mayor, stressed that he is not looking to start a political quarrel with Reeves, the Mississippi governor. But he said there are limits to what he can accomplish as an individual mayor and that he’s eager to see more state engagement with his city.

For instance, Lumumba said that there could be opportunities to coordinate on testing initiatives, or the symptom tracker program the city has launched, or on a recovery strategy.

He also said the city is in need of any support that the state can provide when it comes to offering mental health services. Lumumba said this is a longstanding concern that has been heightened as he and others in Jackson worry about an increase in domestic violence calls and suicides, as the virus forces people to stay at home more.

“I can reach out to mayors of other cities and ask them to employ some of the same restrictions, or to be a part of our effort,” he said. “But I’m not the governor.”

“The failure to have a top-down approach means that there are going to be gaps that we can’t fill,” Lumumba added. “I don’t think that we can do this in a piecemeal way.”