Fourteen years ago this July, I crowded into a gymnasium in Roanoke along with hundreds of other newly minted J.D.s, waiting to take the exam that would determine whether we would be allowed to practice law in the Commonwealth of Virginia. But in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it looks certain that this year’s crop of law-school graduates will be skipping this rite of passage, at least temporarily.

Though the bar exam is traditionally administered in July, the National Conference of Bar Examiners has already scheduled alternative dates for the fall. Meanwhile, a growing number of state bars have declared that they will permit new grads to practice law under the supervision of a licensed attorney until the bar exam can be offered again. Other states are considering waiving the exam requirement entirely for people who complete a term of supervised practice.

All of which raises the question: Was the exam necessary in the first place? In an era of specialization, few lawyers will ever use more than a tiny fraction of the material covered on the bar exam. But, for state bar associations, the exams are a useful way to hold down the number of lawyers.

As the nation’s economy and health-care system struggle to adjust to the pandemic, more and more states are reexamining some of their oldest occupational and business regulations—rules that, although couched as protecting consumers, do far more to limit competition. And for those of us who have long questioned the supposed benefits of these policies, their erosion is welcome, even if the pandemic that caused it is not.

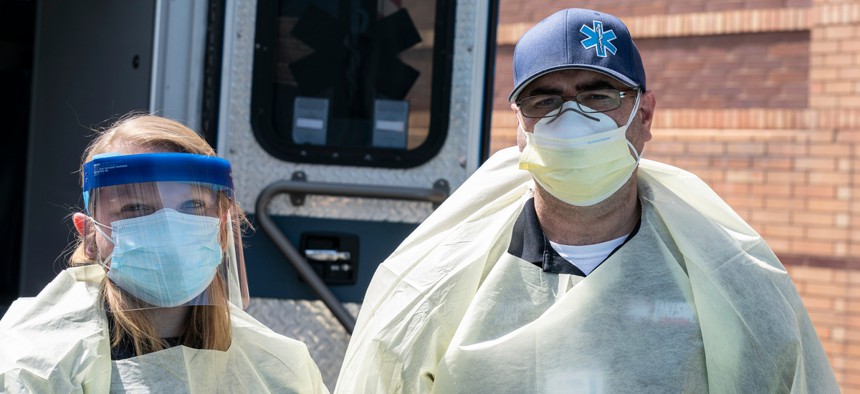

Right now, of course, much of the attention is correctly focused on barriers to work in the health-care industry. Yet here, where the state’s interest in promoting public health and safety is undoubtedly highest, we are seeing some of the most sweeping reforms in decades. While some states have ordered their occupational-licensing boards to speed up the licensure of new health-care practitioners, others—such as Indiana—are granting immediate licensing reciprocity to any practitioner licensed in any state. Even Florida, which has long jealously guarded its occupational-licensing regime to prevent semiretired snowbirds from poaching on the locals’ turf, has gotten in on the act, allowing out-of-state health-care providers to practice telemedicine in the state without a license.