Investigators Found Alabama’s Prisons Are Plagued by Rampant Violence. Is Sentencing Reform the Answer?

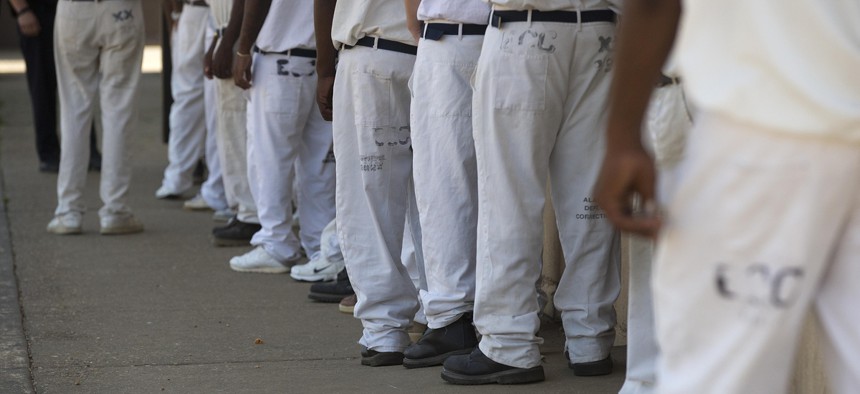

At the Elmore Correctional Facility in Elmore, Ala. AP Photo/Brynn Anderson

The Justice Department says much of the abuse in the state’s prisons stems from overcrowding. Advocates say overcrowding is caused by laws that result in harsh prison sentences that are out of sync with the rest of the country.

The U.S. Department of Justice last week released its second report on civil rights abuses in Alabama’s prison system in just over a year, declaring that the state has allowed a culture to develop “where unlawful uses of force are common.” Taken together, the two reports paint a devastating picture of Alabama’s 13 overcrowded and understaffed men’s prisons, where the rates of homicide, suicide, rape, and officer abuse-of-force far exceed the average in other state prisons across the country.

The findings didn’t surprise Ebony Howard, a senior supervising attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center, who said the problems described by the Justice Department have been “consistent for decades.”

“It’s hell,” she said simply. “What’s happening in Alabama prisons goes beyond punishment. The people there haven’t just had their liberty taken away from them, they've had their humanity taken away.”

Federal investigators agreed that what incarcerated people endure in the state amounts to unconstitutional cruel and unusual punishment. The latest report describes correctional officers beating people in handcuffs and, in some cases, inflicting injuries so severe they led to death. They also noted that stabbings and sexual violence perpetuated by incarcerated people often go unnoticed because of a severe shortage of guards and a lack of cameras. The report’s authors blame many of the problems on the fact that too many people are packed into the state’s prisons, writing that “the severe and pervasive overcrowding increases tensions and escalates episodes of violence between prisoners, which lead to uses of force.”

The Alabama Department of Corrections said in response that they “have been working diligently to redesign and rebuild our correctional system from the ground up to effectively address our longstanding challenges, including staffing shortages, capacity, and facility safety.”

The new report echoes many of the findings of the 2019 DOJ report, a point that has frustrated civil rights advocates in the state who say things have not improved since then and want to see the federal government take a stronger role in reforming Alabama’s prisons, possibly through a consent decree. Proponents say this process, which involves a judge-enforced agreement between the federal government and a local justice system, helps ensure certain policy changes are made. But while the DOJ under President Obama embraced this tactic to bring changes to police departments, jails, and prisons, the program has been severely curtailed under President Trump.

Still, the systemic investigations retain some value on their own, said Jonathan Smith, the executive director of the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs and the former chief of the special litigation section of the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division. “The reports are very important because they set a baseline of facts and are a predicate for future action,” he said. “But the reports in themselves are not remedies. The problems described in the reports are so deep, so long-standing, and so complex to solve, that without a durable agreement that is enforceable over time, they will be almost impossible to solve.”

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall is firmly against the prospect of a consent decree in the state, saying he felt ambushed by the latest report and had been working on a settlement with the federal agency. Marshall pledged he “will not submit our state to judicial oversight of our prisons, with the DOJ as the hall monitor.”

DOJ officials have given Alabama 49 day to agree to a consent decree—but the agency under Trump has yet to sign off on a single consent decree. Like its ongoing probe in Alabama, the Trump DOJ in the past few years has continued an aggressive investigation into the Springfield, Massachusetts police department, but hasn’t so far pushed for a decree. The DOJ did not respond to a request for comment as to whether they would sue the state to seek a consent decree.

But even if the DOJ was interested in moving forward with a consent decree, which could address things like correctional officer training, accountability procedures, and data collection, such a process would miss a key element, Smith said. “One of the major drivers of these problems is severe overcrowding,” he said. “That is not a problem that can be solved quickly or by a consent decree. Part of the long-term process for the state has to be reckoning with the fact that Alabama locks up a lot of people for a very long time.”

But many advocates say they doubt Gov. Kay Ivey will move to change sentencing, noting that in 2018 she moved to reduce parole hearings, something that the ACLU found worsened prison overcrowding this year.

For her part, Ivey has said in response to the report that she wants to see “infrastructure investment[s]” in the state system, including more guards, rehabilitation programs, and mental health services. Ivey also noted that she believes the state will reach a “resolution” with the federal government on the identified issues.

That response “is not in proportion to the scale of the problem,” Howard said. “This is linked to the larger legacy of over-incarcerating Black and Latinx people in this country … That’s a huge order to fix. But a big first step is look at how we’re incarcerating people.”

A spokesperson for Ivey said that “the governor has said time and again that the challenges facing our corrections system are multifaceted and require a multifaceted, Alabama solution. That includes elements from improving our prison infrastructure to making reforms in criminal justice policy.”

The key reform that advocates like Howard want to see revolves around changing the state’s strict sentencing laws that contribute to severe overcrowding, something Ivey and the Republican-controlled legislature earlier this year showed some support for.

Like many states, Alabama took a “tough on crime” approach in the 1980s and 1990s, reducing the bar for felony status for many crimes while at the same time increasing the length of sentences. But while other states have worked in recent years to reduce their prison populations by eliminating mandatory minimums, “three-strikes” laws, and other punitive policies that put more people in prison for longer periods of time, Alabama has not followed suit.

Reports have found Alabama’s sentencing laws are disproportionately harsh compared to other states—with the state’s habitual offender law resulting in hundreds of people serving life for crimes as minor as petty theft. As a result, about 18% of the prison population was serving a life sentence in 2018, and another 30% was serving 20 years or more. Black people often receive the stiffest sentences, and account for 55% of the prison population while accounting for just 26% of the state’s population.

But while prisons in Alabama have been overcrowded for decades, advocates say that the legislature and multiple governors have been unresponsive to calls for sentencing reforms that would reduce the population. In 2000, the legislature created the Alabama Sentencing Commission and tasked it with revising policies to reduce overcrowding—but the new guidelines it suggested in the early 2000s were largely ignored by lawmakers.

In 2006, the Alabama Sentencing Commission’s annual report noted that “most of this year’s legislative recommendations … have been introduced in the legislature before” and were not implemented “because other matters were given priority.” Recommendations in subsequent years were similarly delayed.

The first major sentencing changes in the state came in 2013 and 2015, which combined reduced the state’s prison capacity from 200% to around 160%. Still, advocates say not nearly enough has been done to bring Alabama’s sentencing laws in line with the rest of the country and that the legislature needs to act quickly to address the problem—especially when challenges with overcrowding are made more deadly by the pandemic.

Earlier this year, Ivey supported two bills introduced in response to the 2019 DOJ report—one that would have expanded parole and one that would retroactively apply sentencing guidelines passed in 2013 to those sentenced before that date. The sentencing measure passed out of a House committee, but didn’t move any further during the legislature’s reduced session following the coronavirus outbreak.

Whether those bills will see new life following the new report is yet to be seen. When asked whether she thinks there will soon be the political momentum to change sentencing laws, Howard said that “despite evidence to the contrary,” she remains hopeful.

“I am a Black woman in America with a Black husband and Black children. I live in Alabama and plan to be here until the day I die,” she said. “I have to believe that as long as we continue to engage, there will be hope … That is the legacy of the people who came before us who fought similar fights.”

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: The power and danger of social media for law enforcement