About 750,000 People Are in Jail On Any Given Day. Can They Vote?

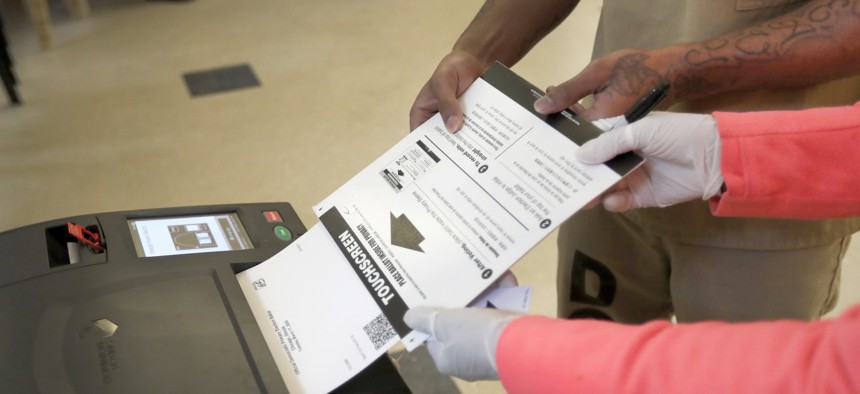

An incarcerated person casts his ballot for the March 17, Illinois primary at the jail in Chicago. AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast

A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative says that most people in jail are eligible to vote, but ultimately won’t be able to due to barriers to voter registration and lack of access to ballots.

About 750,000 people are incarcerated in local jails on any given day, and the vast majority of them are eligible to vote—but most of them won’t end up casting a ballot on November 3 due to a myriad of barriers. Whether voting or registering to vote is possible for incarcerated people awaiting trial differs state by state and sometimes even jail by jail, according to a new report from the Prison Policy Initiative.

The result of a confusing mix of policies is widespread voter suppression, said Ginger Jackson-Gleich, a lawyer for PPI and an author of the report. “One of the most vexing aspects of this issue is that state law varies [and] there are thousands of counties in the United States and each of those counties is likely to have a jail and those jails are administered differently,” she said. “This is a very decentralized process and how it operates causes a lot of unique problems.”

Local election officials often don’t know who in the jail might be eligible to vote, leading to confusion among jail staff and people in detention. But the vast majority of people in jail are eligible—such as people who are awaiting trial, who make up over 550,000 of the people in local jails. (People held pretrial are eligible unless they have a prior felony conviction in a state that strips voting rights from people with certain criminal records). In some states, people serving post-conviction sentences for minor misdemeanors also have the right to vote. This information usually isn’t conveyed to people in detention or staff, meaning people are “frequently confused about eligibility.”

“One of the biggest barriers to voting in jail is the fact that local election officials often don’t know that most people in jail can vote, and it’s not unusual for such officials to provide incorrect information in response to questions about the issue,” the report reads.

Even when people in jail know they’re eligible to vote, registration poses its own challenges. Most people in jail are denied internet access, so requests have to be done by paper forms. In some states, these forms require a form of ID to complete registration—but people in jail don’t have access to drivers’ licenses or passports, as they are confiscated during the intake process. Jail mail can also be delayed, leading to missed registration deadlines.

Jail churn poses another problem. The average stay in jail is just three to four weeks, meaning that people who applied for an absentee ballot at their home address, but end up incarcerated on Election Day can’t vote. The same applies to people who applied for their absentee ballot from jail but are released before Election Day.

If people in jail are able to register to vote at the correct time, they still face the issue of absentee voting behind bars. In the 16 states that only allow absentee voting for an approved list of conditions, nine of them don’t list incarceration as a justification for getting an absentee ballot, essentially barring people in jail from voting.

In some states, groups like Common Cause and the ACLU have been agitating to get the state officials to remove some of these barriers to registration and voting. In Massachusetts, a coalition wrote to the state attorney general and secretary of the commonwealth on September 30, requesting an immediate investigation into ways the state could improve turnout among incarcerated people. “We understand the great many burdens on election officials … especially during this time, but incarcerated eligible voters are eligible voters whose right to vote means little without true access to the ballot,” the groups wrote in a letter.

To Jackson-Gleich, the answer to many of these problems seems obvious. “I think that the clearest situation to this would be to make voting machines available in every jail on election day,” she said.

That idea is already in place in at least one jail. During the March primary this year, Cook County Jail in Chicago installed voting machines behind bars, allowing people to cast their votes as if the jail were a regular polling place. About 1,500 pretrial detainees voted during that election, according to officials, far surpassing the number of people who had voted in the 2016 primary and general elections, when people in jail had to vote via absentee ballots.

The movement to push for in-person voting in jail was led by civic education organizations and grassroots voter registration groups, who also encouraged Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzer to sign into law a measure that requires Cook County to have a polling place at the jail for every election and requires smaller county jails to take steps that would make absentee voting more accessible. Related legislation that Illinois passed requires civics education for all people leaving correctional facilities, including information about how to register to vote and cast a ballot. When he signed these measures in 2019, Pritzer called them indicative of a “a new day in Illinois” where finally “we understand that every vote matters and every vote counts.”

Jackson-Gleich said she’d like to see more initiatives to allow people in jail to vote in-person, or other creative efforts to get out the vote in jails. Rhode Island, for example, made the state Department of Corrections an official voter registration agency to boost the participation of people in jails. Colorado requires county clerks to coordinate with sheriff’s offices to register people in jail.

The true measure of success would be that “every person who is in jail either before Election Day or on Election Day has the equal opportunity as any other American to vote,” she said.

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: How digital tech is giving old documents new life