Cities Declared Racism a Public Health Crisis. What Now?

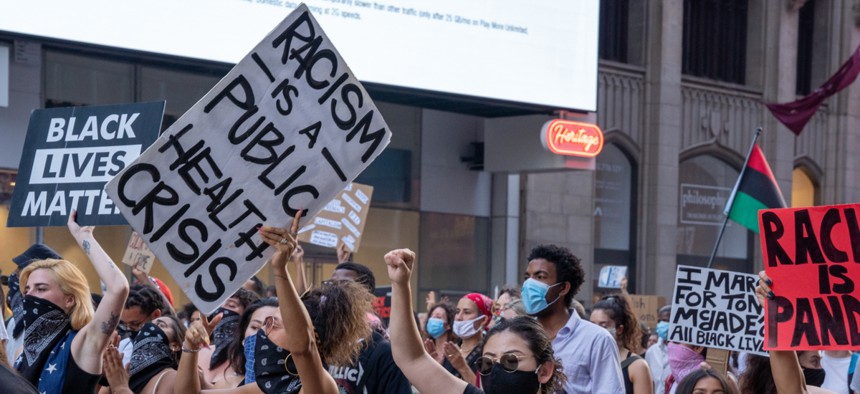

A protest against police brutality in New York City. Shutterstock

This summer, many local governments approved resolutions declaring racism to be a public health crisis. Why now? And what comes next?

In June of 2019, Cook County Commissioner Dennis Deer proposed a novel resolution for his colleagues to consider. He wanted the county, which includes Chicago, to declare racism a public health crisis. “I’ve seen racism all my life,” said Deer, who grew up in the city’s North Lawndale neighborhood. “I’ve seen what it looks like when a lack of inclusion runs rampant.”

Deer, who chairs the county’s health and hospitals committee, represents parts of Chicago’s South Side, including predominantly Black neighborhoods like Englewood where he says the public health crisis of racism is on full display. Englewood’s residents have a life expectancy of 60, which is astonishingly low compared to predominantly white neighborhoods like Streeterville, where the life expectancy is 90. The two neighborhoods have the largest divergence between their life expectancies of any neighborhoods in the same city in the entire country, an NYU School of Medicine analysis found last year.

“We had to finally talk about this publicly,” Deer said. “I knew something had to be done.”

But what he didn’t know was that within a year, cities and counties across the country would take similar steps. When Deer crafted the resolution, which was approved by his fellow commissioners the next month, only one other place, Milwaukee, had passed a measure declaring racism a public health crisis. Cook County borrowed some of the language in its resolution from the one in Milwaukee, including the last commitment: the county will encourage other local, state, and national entities to recognize racism as a public health crisis.

Since then, more than 130 cities, counties, and states have declared racism a public health crisis, with many of those declarations winning approval this summer following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the subsequent nationwide protests calling for governments to address legacies of racism and discrimination. That movement grew as people also began to realize the profound disparities in who got sick and died from the coronavirus.

Deer said he’s been shocked by the sudden embrace of the idea and the requests he’s received from other counties—he was even contacted by Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, who recently introduced legislation calling on the federal government to declare racism a public health crisis.

“I never thought it would balloon like this,” he said. “Not in my wildest dreams.”

What does ‘Racism is a Public Health Crisis’ Mean, Exactly?

While the idea of a government agreeing with the phrase “racism is a public health crisis” has gained steam at the state and local level lately, the concept isn’t new. Public health researchers have been talking about the social determinants of health since at least the 1990s, connecting racist practices in housing, health care, employment, and other areas to worse health outcomes for Black Americans.

These crises are often talked about individually: the Black maternal mortality crisis, the high rates of asthma among Black people living in neighborhoods suffering from significant air pollution, the twin crises of mass incarceration and over-policing in Black communities. Put simply, declaring racism a public health crisis means the government is officially connecting the dots and talking about racism as the common root of these problems. But the data supporting these assertions has been around for years—so why is the idea gaining steam now?

“What’s changed is Covid,” said Ruqaiijah Yearby, the executive director of the Institute for Healing Justice and Equity at Saint Louis University. “The pandemic unfortunately highlights racial inequalities quite well, and policymakers are beginning to see examples of how things like housing and education and health care connect. They’re also starting to see that Covid is going to exacerbate these disparities unless we address them now.”

Yearby, along with Crystal Lewis, a health equity and policy fellow at the Institute, recently started tracking declarations calling racism a public health crisis to figure out how cities, counties, and states are talking about the issue. Lewis said that good resolutions connect the public health crisis to long-term economic inequality and show how racism in housing, health care, education, employment, and law enforcement, results in physical and physiological harm. “The best resolutions are specific and explain how racism has a multifaceted impact on health outcomes,” she said. “But the variability in the resolutions shows there isn’t even a shared idea of what racism is,” Lewis said.

What Do Resolutions Mean for Public Policy?

Along with different definitions, the resolutions vary in terms of impact. Several governors, including those in Michigan, Nevada and Wisconsin, issued their own. Some of these statements, like the one from Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers, are just that—statements—and don’t include any new requirements for state agencies or legislative suggestions to remedy the crisis. Others, like the one from Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, included mandates that required the state to form advisory groups, train government employees in implicit bias and review state laws that perpetuate inequities.

The declarations at the city and county level are similarly scattershot. The resolution in Los Angeles, passed by the city council in June, “asserts that racism is a public health crisis affecting our entire city” but doesn’t lay out clear policy next steps. Instead, the city committed to measures like “conduct[ing] an assessment of internal city policy and procedures” and “identify[ing] specific activities to further enhance diversity.”

These types of resolutions could be looked at one of two ways: with frustration over the lack of teeth and enforcement mechanisms or with optimism that local governments are taking the first step. Yearby said she can see both sides. “Even the fact that people are saying ‘racism is a public health crisis’ is an important step, because historically, a lot of people have said racism doesn’t exist or doesn’t affect us,” she said. “But we still want to see more, especially in terms of budgets.”

Only a handful of cities have set specific policy goals or committed funding to achieve them. Washtenaw County, Michigan pledged in their resolution to increase the budget for both the public health department and racial equity office, with the author of the resolution saying that "words alone will not work” and the county must “move on the action items.” In Boston, Mayor Marty Walsh declared racism to be a public health crisis and said he would reallocate $12 million of the police department’s overtime budget to public health initiatives.

Compared with these examples, it’s easy to say that declarations without funding attached aren’t enough, said Lewis, the health equity fellow. But getting a government to publicly assert that racism is a crisis shouldn’t be taken for granted, because in several places, the resolutions have faced significant opposition or even failed. The town attorney in Orange, Connecticut, which recently held a public forum about racism and public health, said that the declaration could have “unintended consequences.” Resolutions failed this summer at the Minnesota state legislature, the city council of Lowell, Massachusetts, and the township of Franklin, Ohio. “The reasons why they failed are often the same,” Lewis said. “It’s usually ‘racism isn’t a problem where we live.’”

What Will Next Steps Look Like?

Durham County, North Carolina passed a resolution in June that didn’t include concrete next steps—but Commissioner Brenda Howerton said that it shouldn’t have. The solutions to the problems laid out in the resolution—like higher rates of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and low birth weight among Durham’s Black residents—should come from the community itself, she said.

“We’ve got some smart people in this community,” she said. “I want them to drive the solutions and for us as a county government to figure out how we get there.”

In the meantime, the county government is considering the recommendations of a racial equity task force that delivered a report in July. Howerton said she understands why people might be frustrated that things aren’t moving faster because “the community is in pain.”

“I get that people are tired of task forces. They want action,” she said. “Racism has undergirded everything we do in this country. But putting a Band-Aid on it doesn’t get to the crux of the issue. We have to drill down and look at our systems. That’s the only way to identify the things we can do that will really impact people’s lives.”

Places like Durham may again end up taking inspiration from the early frontrunners like Cook County. A year after Cook County passed their resolution, Commissioner Deer said that things are moving along: the county hired its first director of diversity and inclusion and the preliminary budget for 2021 has $50 million earmarked for equity-related projects. But that wouldn’t have happened without the first step of declaring racism a public health crisis, he said. “We had to get people talking about it. We needed a paradigm shift,” Deer said.

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Emissions Exposure May Increase Covid-19 Mortality