Wealthy Donors Spend Big to Expand Voting Access

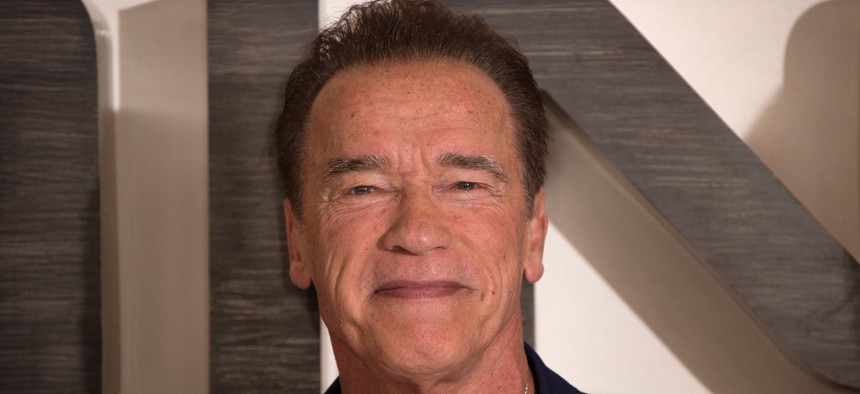

Arnold Schwarzenegger, an actor, businessman and former Republican governor of California, is funding grants to open polling places in Southern states ahead of the presidential election. AP Photo

Connecting state and local government leaders

With limited resources, governments turn to the super wealthy for election help.

This story was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity and Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Poll worker training doesn’t usually involve a call to do 200 push-ups. It also doesn’t usually involve Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“Let’s pump it up!” the actor, businessman, former professional bodybuilder and former Republican California governor told a crowd of 16 surprised trainees in Muscogee County, Georgia, over Zoom earlier this month. “Let’s pump it up,” the trainees sitting in a church gymnasium dutifully repeated through their masks.

Schwarzenegger had popped in for more than a pep talk: He announced that he was giving the county a $210,675 grant via the University of Southern California Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy to cover hazard pay for poll workers and other election expenses.

“I play the superhero in the movies,” said Schwarzenegger, whose stubble is now white but whose voice was unmistakable. “But you are the true democracy superheroes.”

None of the Muscogee County trainees got out of their folding chairs and did push-ups during the call. But election officials seeking money to offset unprecedented expenses this year have had to show real endurance.

Election officials have spent months begging local governments, state authorities and Congress for additional cash, with limited success. They are staring down a range of unanticipated costs associated with running a high-turnout election in a pandemic—everything from the equipment needed to process a crush of absentee ballots to personal protective equipment and hazard pay for poll workers concerned about exposure to the virus. Many have already spent years making hard choices about how to best allocate limited resources.

Now, Schwarzenegger and other rich donors are stepping up. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan have funded $400 million in election administration grants awarded through two nonpartisan nonprofits. Schwarzenegger, through his institute at USC, is awarding grants aimed at reversing the impact of polling place closures and offering more in-person access to voting. The institute had awarded 30 grants totaling seven figures as of last week, and it isn’t done yet.

For some, the infusion of private dollars is troubling.

The Thomas More Society, a conservative law firm, brought lawsuits against local officials in at least eight states over the grants from Zuckerberg and Chan, arguing that the donors were directing their money to jurisdictions with a history of voting for Democrats, and that state and federal law doesn’t allow cities and towns to accept private dollars. So far, federal judges in Minnesota and Wisconsin have ruled that counties in those states could receive private grants for election administration costs. And donors have said their efforts aren’t aimed at helping a particular party.

In Louisiana, the secretary of state initially encouraged local election officials to apply for private grants, but the state attorney general said accepting the money would be illegal. In a state court lawsuit this month against the Center for Tech and Civic Life, the group that has overseen most of the grants funded by Zuckerberg and Chan, Republican Attorney General Jeff Landry said the grants were an attempt to inject “unregulated private money into the Louisiana election system.” Blocking this, he wrote, protects the integrity of state elections “by ensuring against the corrosive influence of outside money.”

Landry’s office responded to an interview request by providing his court filing. His stance appears to be deterring parishes from applying for grants. Christian Grose, an assistant professor at USC who is administering the Schwarzenegger grants, said the institute has received no applications from Louisiana or Florida, though election officials in both states were contacted and told they were eligible to apply.

Some voting rights advocates say the main concern should be that local election officials are in a situation where they are dependent on outside resources to shore up massive funding shortfalls in election administration.

While she’s excited people have donated much-needed resources, it is still “unfortunate that we chronically under-fund our elections,” said Myrna Pérez, the director of the Brennan Center's Voting Rights and Elections Program at New York University School of Law, which earlier this year estimated state and local officials needed $4 billion in additional funding to properly administer this election.

Congress, as part of the CARES Act, allocated $400 million in March for election assistance, but President Donald Trump and other Republicans have opposed additional funding that may improve mail-in voting across the country.

“My big hope is that the American public will make it very clear to our politicians that our elections are so important they want to make sure they have a sufficient amount of funding,” Pérez said.

Many election officials agree. “Of course, the amazing philanthropy that we saw late in the cycle this year has made it possible to run this election well. It shouldn't come to that,” said Pennsylvania Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar, a Democrat, during a press call Oct. 20.

Schwarzenegger announced last month that he would give grants to support in-person voting access in places that, because of a history of voter suppression, had been required to seek permission from the Department of Justice for polling place reductions and other voting changes under the Voting Rights Act.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down that requirement in Shelby County v. Holder. Schwarzenegger said he’s responding to reports of poll closures disproportionately affecting communities of color in the wake of the decision.

The Center for Public Integrity and Stateline in September released national data on polling places in past elections, data aimed at aiding reporting and research on the impact that polling place closures and changes could have on the 2020 election.

Since Schwarzenegger announced the grants on Sept. 23, the staff at the Schwarzenegger Institute has been scrambling to let election administrators know the money is available, set up a process to quickly evaluate applications and get the grants out the door in time to make a meaningful difference for the election.

Grose said Schwarzenegger was troubled by reports of polling place closures. “He was concerned about it and decided he would do something.”

The time between the announcement and awarding the first grant was less than a week, said Conyers Davis, global director of the Schwarzenegger Institute. Grose said the Institute randomly called 300 election administrators in the targeted states to tell them about the grants. Grose is planning a post-election audit to examine the impact of the grants and to determine why some counties declined to apply for them.

In some cases, local election officials wanted to make sure the money was real. “Unfortunately, in these times, when people start telling you they have a lot of money [and] they’d like you to send them information — we’re a little suspicious at this time of the year,” chuckled Remi Garza, the election administrator in Cameron County, Texas, where 90% of the population is Latino.

Garza double-checked with the Schwarzenegger Institute, then drafted a plan to add two additional voting “supercenters” open to anyone in the county. He submitted it by Friday and heard he’d won the $250,000 grant on Monday. He expects each of the sites to serve 7,000 to 10,000 voters. The new locations also will allow him to more easily expand curbside voting and alleviate congestion throughout the county.

Cameron County also got a grant from the Center for Tech and Civic Life, Garza said, and the private money is “really going to make a difference in how we are able to conduct this election.”

Nancy Boren, the director of elections and registration for Muscogee County, was visiting her daughter, a law school student, when her daughter asked her if she had seen Schwarzenegger’s tweet about the election grants. Boren applied immediately, and wound up securing the Schwarzenegger grant, as well as $412,000 from the Center for Tech and Civic Life.

She had already worked out a deal to use the Columbus, Georgia, convention center for free for a week of early voting. Boren used the Schwarzenegger money to open it 10 days earlier. She also was able to open two other sites earlier than scheduled, and add hazard pay for poll workers.

Boren used most of the Zuckerberg/Chan money to cover expenses related to the surge in absentee ballots, including the purchase of a machine to open envelopes containing them. Asked what she would have done without the grants, she paused. “Letter openers?”

Not all the grants are in the six-figure range.

Election officials in Craig County, Virginia, on the West Virginia border, were struggling to fill poll worker positions before the state’s June primary, said Susan Creasap, the secretary of the county election board. The county will use its $4,032.60 grant from the Schwarzenegger Institute to boost Election Day pay from $120 to $150 and to keep open a small polling place that serves voters who otherwise would have to travel over a mountain, treacherous in bad weather, to cast their ballots.

Election administrators made a bipartisan plea for more money from Congress, and didn’t get it, said David Becker, founder and executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, which received $50 million from Zuckerberg and Chan and has awarded grants to 23 states and Washington, D.C. “The need was just very, very great,” he said on a press call.

Schwarzenegger, meanwhile, sounds as surprised as anyone else to find himself paying for polling places.

“I tell you,” Schwarzenegger said to the Muscogee County poll workers, “never in my wildest dreams did I ever think when I came to America more than 50 years ago that one day I would be financing or giving money to open polling places in Georgia.”

Carrie Levine is a senior reporter at the Center for Public Integrity. Matt Vasilogambros writes about immigration and voting rights for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: One State Will Deploy National Guard to Nursing Homes