COVID-19 Eased Drug Treatment Rules—And That Saved Lives

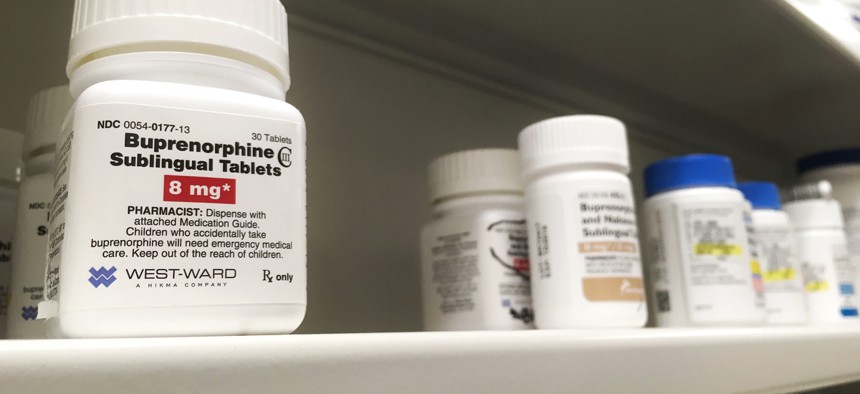

The DEA lifted a restriction requiring people taking buprenorphine for the first time to do so under the supervision of a doctor or nurse. Shutterstock

A deadly year could have been much worse without phone counseling options.

This story originally appeared on Stateline.

When the pandemic hit in March, people in treatment for substance use disorder worried they would lose access to the medications and counseling they rely on.

In most places, that hasn’t happened.

In fact, for many in recovery, access to treatment has gotten a lot easier.

Since March, some patients have been allowed to take the life-saving medication methadone at home instead of risking COVID-19 exposure by visiting a crowded clinic every day. Buprenorphine patients have had their prescriptions renewed by phone instead of visiting their doctors every week or month. And addiction counseling and crisis support has become available over the phone.

Now, physicians and addiction experts are advocating for extending the emergency federal and state rules they say have saved thousands of lives by dramatically expanding access to addiction treatment.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine and other behavioral health organizations are supporting a bipartisan bill in Congress that would continue the addiction treatment telehealth rules beyond the pandemic.

“Telehealth sessions have been a lifeline for those walking the long road to recovery during a stressful, isolating time,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a Rhode Island Democrat who is co-sponsoring the bill, in a news release.

“Our bipartisan legislation would ensure that recovery support continues to be widely available from the comfort of home after the pandemic wanes.”

Despite the changes, drug overdose deaths are still rising. Experts say that’s largely due to huge increases in the supply of illicit drugs, particularly those containing the deadly opioid additive fentanyl.

The fear, stress, isolation and hopelessness that many Americans have experienced during the pandemic are likely causes of drug overdose deaths as well, said Dr. Paul Earley, president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Nationwide, overdose deaths have been climbing over the past year, putting 2020 on track to be the deadliest yet for drug overdoses.

This month the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published provisional data collected from states showing that more than 81,000 people died from a drug overdose in the 12 months ending May 2020, an 18% increase over the previous 12-month period.

That period mostly predates the pandemic, but overdose data collected by individual states since May shows continued increases. In Ohio, for example, a harm reduction group reported a rise in deaths through June that represented a 20% increase in the first six months of 2020 compared with the same period last year.

And in Minnesota the state health agency this month reported that drug overdose deaths in the state shot up 31% during the first half of 2020 compared with the first half of 2019.

Nationwide, if the nearly 12% rise in overdose deaths in the first five months of 2020 continues, the year-end total could dwarf death counts of previous years.

Those numbers are shocking, but treatment experts say thousands more likely would have died without the new rules and the resiliency of the addiction treatment industry.

“We were all very worried in the beginning of the pandemic,” said Linda Hurley, CEO of CODAC Behavioral Healthcare, a nonprofit addiction treatment provider with eight clinics in Rhode Island and one in Massachusetts.

“When you think about it, the antithesis of a recovery support system is isolation,” she said. ”And at the same time, the ultimate method of mitigating exposure to COVID is isolation. You could see how clearly those two things were connected in an exacerbating way.”

Allowing treatment providers to counsel clients over the phone has prevented a worst-case scenario, Hurley said. The positive effects of telehealth and other changes suggest that some of the pre-pandemic addiction treatment rules didn’t make much sense.

“I believe this pandemic has demonstrated that our trade, our medicine, has been overregulated for decades,” Hurley said.

Staying Connected

Before the pandemic, Medicare did not reimburse addiction treatment providers for audio-only telehealth counseling, even though similar consultations were covered for other health conditions. And only a few state Medicaid programs covered telephone counseling.

Addiction counseling by video or telephone can now be reimbursed under new rules, though the regulations are slated to expire when the pandemic emergency declaration lifts.

In a survey conducted by researchers at Brown University from August through October, a huge majority of people in treatment for drug addiction said they preferred talking to their counselors by phone rather than in person.

More than 90% of the surveyed patients said addiction counseling by phone was not only easier, but also more effective than in-person counseling.

For many patients, addiction counseling by phone can be less intimidating, said Dr. Stephen Taylor, chief medical officer at Pathway Healthcare, an addiction treatment company.

Once the pandemic began, he said, the counselors who work at his treatment facilities in Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee began converting their scheduled in-person visits to Zoom or phone calls when patients told them they were fearful of visiting. Both counselors and patients quickly adapted, he said.

But in New York City, Allegra Schorr, co-owner of West Midtown Medical Group, a methadone treatment facility, said some of her patients say they miss the routine of visiting the clinic every day and seeing the doctors, nurses and other patients.

“Where we know there are co-occurring mental health disorders, isolation and depression, the need to connect is still there. And for some, it’s not as simple as a phone call.

“It’s very mixed,” she said. “Some people keep asking ‘When can we come back?’”

Prescription Changes

In March, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration responded to the pandemic by swiftly easing restrictions on the opioid addiction treatment medication methadone, allowing many more patients to take home a month’s supply of the daily maintenance drug.

At the same time, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration—which oversees the use of buprenorphine, another Food and Drug Administration-approved addiction treatment medication—relaxed rules that previously required patients to visit a medical professional at least monthly to renew their prescriptions.

The DEA also lifted a restriction requiring people taking buprenorphine for the first time to do so under the supervision of a doctor or nurse. Now medical professionals can guide new patients by phone as they begin treatment.

The bipartisan bill in Congress would allow doctors to continue issuing and renewing buprenorphine prescriptions by phone.

State Initiatives

Soon after the federal rule changes took effect, states and cities responded by tweaking their Medicaid and other addiction treatment rules. In some cases, states provided funding for innovative new treatment services.

“We saw a lot of scrappiness among treatment providers who tried new things that previously weren’t possible,” said Dr. Brendan Saloner, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. His research team has conducted more than 500 interviews with drug users and people in treatment to gain a better understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected their lives and their treatment.

In Rhode Island, the state behavioral health agency set up a hotline in June for people seeking help with drug addiction. The trained professionals who answered the phones connected people to treatment facilities where licensed professionals prescribed buprenorphine over the phone and guided them through getting started on the daily medicine.

In New Jersey, New York, Ohio and Washington state, treatment clinics during the pandemic started making curbside and doorstep deliveries of both methadone and buprenorphine for patients who were quarantined or isolated because of age or health issues.

In New York City, teams of city-employed couriers used city vehicles to deliver the medications to homeless shelters, homes and hotels where patients were quarantined.

Many states dramatically increased supplies of free naloxone, an overdose rescue drug that can be used by friends, family, bystanders and first responders. Delaware announced that people struggling with addiction could order free naloxone by mail.

Maine, Rhode Island and other states expanded free syringe exchange programs, and drug courts in New Hampshire allowed virtual counseling as a way for drug users to avoid imprisonment for drug-related charges.

The Baltimore Model

When many of Baltimore’s other treatment providers temporarily closed at the start of the pandemic, one group’s patient list more than tripled.

Known as Project Connections, the loose coalition of doctors and nurses has provided buprenorphine and addiction counseling from a van parked next to the city’s central booking agency since 2017. Mainly through word-of-mouth, the group has expanded its patient rolls, treating thousands of mostly homeless, uninsured Baltimore residents, with little red tape or oversight.

“Our patients don’t even need an ID to get treatment,” said Deborah Agus, the group’s founder and executive director. That’s because the medical professionals who provide treatment through Project Connections are not organized as an opioid treatment facility, she explained. They work individually, like primary care doctors, so they’ve never been subject to the federal rules that apply to licensed treatment facilities.

In a November article in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, researchers at Johns Hopkins cited the group as an example of how access to treatment can be expanded, even during a pandemic.

“Since we operated mostly outside, not much changed for us,” Agus said. “We were able to stay open through the spring and summer by moving out of the van and setting up tents on the sidewalk. When it got hot, we bought fans. When it got cold in the fall, we bought heaters.”

Now that winter is in full gear, Agus said the group is using telephone counseling to stay in touch with patients. “We didn’t want people to think we’d shut down, though. So, we kept our van parked in the same place with someone sitting outside in a lawn chair to tell people the number to call for help.”

Christine Vestal is a staff writer for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: No More ICU Beds at the Main Public Hospital in the Nation’s Largest County