The Worst-Case Scenario Is Happening—Hospitals Are Overwhelmed

A stretcher is loaded back into an ambulance after EMTs dropped off a patient at a newly opened field hospital operated by Care New England to handle a surge of Covid-19 patients in Cranston, R.I. AP Photo/David Goldman

A new statistic shows that health-care workers are running out of space to treat Covid-19 patients.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, public-health experts have warned of one particular nightmare. It is possible, they said, for the number of coronavirus patients to exceed the capacity of hospitals in a state or city to take care of them. Faced with a surge of severely ill people, doctors and nurses will have to put beds in hallways, spend less time with patients, and become more strict about who they admit into the hospital at all. The quality of care will fall; Americans who need hospital beds for any other reason—a heart attack, a broken leg—will struggle to find space. Many people will unnecessarily suffer and die.

“If, in fact, there’s a scenario that’s very severe, it is conceivable that will happen,” Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious-disease doctor, said in mid-March. “We’re doing everything we can to not allow that worst-case scenario to happen.”

Fear of this scenario drove many of the most stringent stay-at-home orders in the spring. “There will be no normally functioning economy if our hospitals are overwhelmed,” Liz Cheney, a leading House Republican, said a week and a half later.

Yet that worst-case scenario never came to pass at a national level. At the springtime peak, even as Northeast hospitals faced a deluge, 60,000 people were hospitalized nationwide. When the Sun Belt frothed with cases this summer, hospitalizations again reached the 60,000 mark before they started to fall.

A month ago, in early November, hospitalizations passed 60,000—and kept climbing, quickly. On Wednesday, the country tore past a nauseating virus record. For the first time since the pandemic began, more than 100,000 people were hospitalized with Covid-19 in the United States, nearly double the record highs seen during the spring and summer surges.

The pandemic nightmare scenario—the buckling of hospital and health-care systems nationwide—has arrived. Several lines of evidence are now sending us the same message: Hospitals are becoming overwhelmed, causing them to restrict whom they admit and leading more Americans to needlessly die.

The current rise in hospitalizations began in late September, and for weeks now hospitals have faced unprecedented demand for medical care. The number of hospitalized patients has increased nearly every day : Since November 1, the number of people hospitalized with Covid-19 has doubled; since October 1, it has tripled.

Throughout that time, health-care workers have worried that hospitals would soon be overwhelmed. “The health-care system in Iowa is going to collapse, no question,” an infectious-disease doctor told my colleague Ed Yong early last month. The following week, a critical-care doctor in Nebraska warned, “The assumption we will always have a hospital bed for [you] is a false one.”

These catastrophes seem to be coming to pass—not just in Iowa and Nebraska, but all across the country. A national breakdown in hospital care is now starkly apparent in the coronavirus data.

[Read: Hospitals know what’s coming]

It is clearest in a single simple statistic, recently observed by Ashish Jha, the dean of the Brown University School of Public Health. For weeks, the number of people hospitalized with Covid-19 had been about 3.5 percent of the number of cases reported a week earlier. But, he noticed, that relationship has broken down. A smaller and smaller proportion of cases is appearing in hospitalization totals.

“This is a real thing. It’s not an artifact. It’s not data problems,” Jha told us.

Why would this number change? As hospitals run out of beds, they could be forced to alter the standards for what kinds of patients are admitted with Covid-19. The average American admitted to the hospital with Covid-19 today is probably more acutely ill than someone admitted with Covid-19 in the late summer. This isn’t because doctors or nurses are acting out of cruelty or malice, but simply because they are running out of hospital beds and must tighten the criteria on who can be admitted.

Many states have reported that their hospitals are running out of room and restricting which patients can be admitted. In South Dakota, a network of 37 hospitals reported sending more than 150 people home with oxygen tanks to keep beds open for even sicker patients. A hospital in Amarillo, Texas, reported that Covid-19 patients are waiting in the emergency room for beds to become available. Some patients in Laredo, Texas, were sent to hospitals in San Antonio—until that city stopped accepting transfers. Elsewhere in Texas, patients were sent to Oklahoma, but hospitals there have also tightened their admission criteria.

[Read: Hospitals can’t go on like this]

The COVID Tracking Project has found the same phenomenon by looking at a different variable in the data produced by the Department of Health and Human Services: the number of people admitted to the hospital every week. (Jha was analyzing the number of people currently hospitalized.)

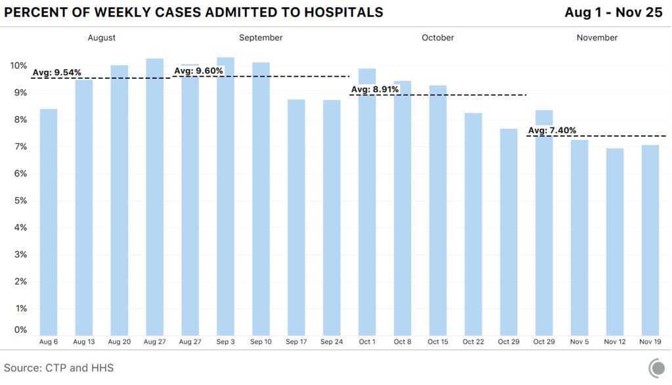

In August and September, about 9.5 percent of Covid-19 cases were admitted to hospitals nationwide, according to federal data. As October began, this case-hospitalization proportion held for about a week. But then cases began to explode, especially in the Midwest and Great Plains, and hospitals suffered strain. In the last week of October, the average number of new Covid-19 cases surged past its all-time high of 66,000 new cases a day. Less than 8 percent of those cases made it into the hospital, a 16 percent drop in the proportion of sick people admitted versus September.

As the pandemic intensified, the fall continued. On November 10, the U.S. recorded more virus hospitalizations than ever before, passing the previous high set during the spring and summer surges. More than 100,000 Americans were diagnosed with the virus every day last month, on average, and more than ever were hospitalized as well. But as facilities ran short on bed space, the fraction of admitted cases fell. Ultimately, only 7.4 percent of Covid-19 cases were hospitalized in November—the lowest percentage yet.

This change may not seem ominous at first. You might expect to see such a divergence, for instance, if testing rapidly increased, so that states were suddenly detecting many more mild cases of Covid-19. But the data don’t show any evidence of this kind of “casedemic”—if anything, they show the opposite. Last month, the number of total Covid-19 tests increased by about a third compared with October, but the number of total cases discovered more than doubled. More people are getting sick.

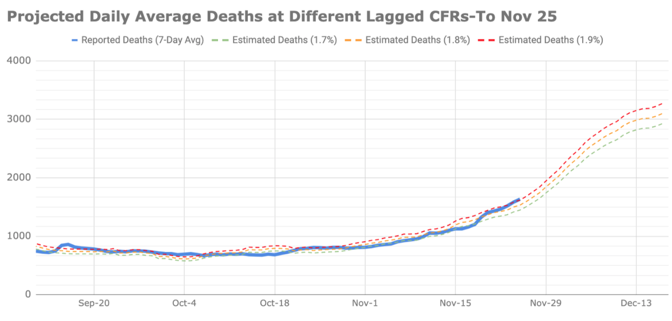

At the same time, the virus seems to be killing a slightly higher fraction of people diagnosed with it. Using a method that accounts for clinical- and data-reporting lags between cases and deaths, for most of October and November, about 1.7 percent of cases resulted in death. But in the middle of November, that number lurched to more than 1.8 percent. While this change may seem small, it represents hundreds of deaths, because many more people are getting sick every day.

In other words, we’re observing exactly the opposite of what you’d expect from a rash of mild cases in the data. The virus seems to be killing more people. And that makes sense: As Yong and our colleague Sarah Zhang have both written, many of our medical triumphs over the virus have come from more attentive and knowledgeable hospital care for COVID-19 patients. (Very few, if any, people outside of a clinical trial have received the cocktail of antibody drugs that President Donald Trump claims is a “cure” for the disease.) Yet a smaller fraction of people are now receiving that expert and conscientious care.

Since March, most of our writing about the pandemic has focused on the near-term future. We’ve described data as worrying or ominous, words implying that the worst is soon to arrive. There’s a good reason for this forward-looking approach: It gives people a sense of what’s coming, and it helps people make decisions to protect themselves or their family.

But ominous no longer fits what we’re observing in the data, because calamity is no longer imminent; it is here. The bulk of evidence now suggests that one of the worst fears of the pandemic—that hospitals would become overwhelmed, leading to needless deaths—is happening now. Americans are dying of Covid-19 who, had they gotten sick a month earlier, would have lived. This is such a searingly ugly idea that it is worth repeating: Americans are likely dying of Covid-19 now who would have survived had they gotten September’s level of medical care.

The first doses of vaccine will almost certainly go out by Christmas. Tens of millions of Americans could have protective immunity within eight weeks. As the days lengthen and the weather warms, the vaccine will become easier to get; more than 100 million Americans may have immunity by the end of February. Many indicators suggest that next summer will be happy and prosperous, and we will gather indoors and outdoors and grin at one another like children in June. But the world will be reduced, and not as wise, because tens of thousands of Americans will be dead when they should be alive.

This story was originally published in The Atlantic. Sign up for the magazine's newsletters.

Robinson Meyer and Alexis C. Madrigal are staff writers at The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: States Are Paying to Hire Nurses for Struggling Hospitals