The Second-Class Treatment of U.S. Territories Is Un-American

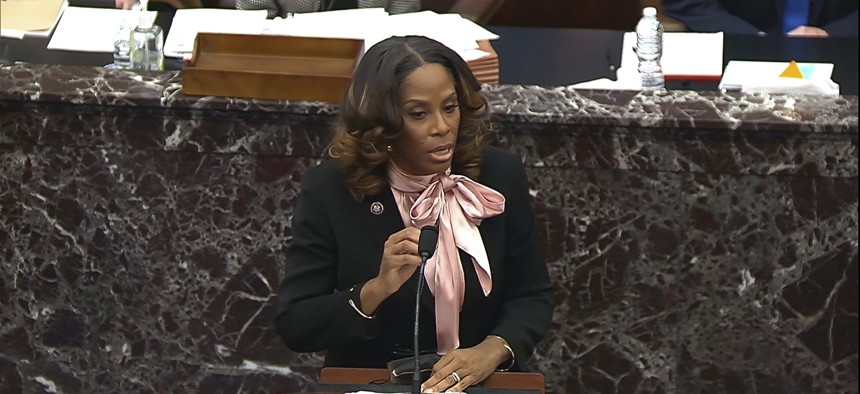

House impeachment manager Del. Stacey Plaskett, D-Virgin Islands, answers a question from Sen. Jacky Rosen, D-Nev., during the second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump. Senate Television via AP

COMMENTARY | We deserve nothing less than the full rights of citizenship, including the right to vote.

This story was originally published by The Atlantic. Subscribe to the magazine’s newsletters.

Last month, I served as a House impeachment manager in the trial of President Donald Trump. My presence on the floor of the U.S. Senate carried a great deal of meaning for me. It also said a lot about America. A Black girl who split her childhood between housing projects in Brooklyn and St. Croix could grow up to become a member of Congress who holds a former president to account. But I was the only Black woman in the room. And although I was making the case for convicting Trump, I hadn’t been able to cast a vote in the House to impeach him. My constituents in the Virgin Islands—U.S. citizens—remain unable to vote for president, lack any voice in the Senate, and have only a nonvoting delegate in the House.

As I said during the Senate impeachment trial, “Every American has the right to vote—unless you live in a territory.”

Our second-class treatment is not just unfair; it is un-American. More than 3.5 million Americans are denied the right to vote in presidential elections, because they live in one of five U.S. territories: Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and my home, the U.S. Virgin Islands. That number is equivalent to the population of the five smallest states combined. More than 98 percent of these territorial residents are racial or ethnic minorities like me—a fact that cannot be a mere coincidence as our continuing disenfranchisement extends well past the century mark.

Our nation’s Founders never intended our country to work this way. Many of them, including Alexander Hamilton, who spent his formative years in my home of St. Croix, risked their lives to reject colonialism. They had experienced taxation without representation, and they wanted no part of it. They understood that governments “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

[Read: Testing territorial limits]

America has from its inception included U.S. territories, and the people who lived in those territories knew that the Constitution protected their rights. Those same people also believed in the promise of full political participation through eventual statehood.

That promise was broken after the United States began acquiring island territories in 1898. Bending to political pressure from President William McKinley and others who supported American imperial expansion overseas, the Supreme Court turned its back on our country’s founding ideals. In a series of highly fractured and controversial decisions known collectively as the Insular Cases, the Supreme Court invented an unprecedented new category of “unincorporated” territories, which were not on a path to statehood and whose residents could be denied even basic constitutional rights. Which territories the Court determined were “unincorporated” turned largely on the justices’ view of the people who lived there—people they labeled “half-civilized,” “savage,” “alien races,” and “ignorant and lawless.”

While other racist decisions from that era, including Plessy v. Ferguson, have long been reversed, the Supreme Court has yet to turn the page on the Insular Cases. Last summer, the Court expressed concerns over these cases—Justice Stephen Breyer called them a “dark cloud”—but stopped short of actually overruling them.

The ramifications of the Insular Cases go well beyond the ability of citizens in the territories to vote. We pay billions of dollars in federal taxes, and yet residents of U.S. territories are denied access to crucial federal support. Otherwise eligible citizens in the territories are denied Supplemental Security Income, leaving our most vulnerable seniors and people with disabilities to fend for themselves. Federal programs, including Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the child tax credit, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, are either capped or denied altogether.

Hurricanes Irma and Maria, which hit the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico in 2017, further exposed the human costs of disenfranchisement. Of the approximately 3,000 deaths associated with these disasters, the overwhelming majority occurred after the storms had passed, showing the devastating consequences of an insufficient federal emergency response. And the coronavirus pandemic has highlighted once again the large health disparities between our residents and those of the states.

[Read: Puerto Rico’s dream, denied]

The Supreme Court will soon tackle questions of federal discrimination against citizens in the territories in United States v. Vaello-Madero, a case about the arbitrary denial of SSI benefits in Puerto Rico that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ruled unconstitutional. This week I joined a letter pressing the Department of Justice to stop defending this kind of discrimination in court. While this case proceeds, I continue to work with my colleagues in Congress to bring an end to this inequality by introducing legislation that provides SSI benefits to residents of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

As I emphasized during the impeachment trial, our country has been given a collective opportunity to ask what America is and who Americans are as a people. These questions extend to the United States’ responsibility to its citizens in its territories, most of whom are people of color. We deserve nothing less than the full rights of citizenship, including the right to vote.

Stacey Plaskett, who represents the people of the U.S. Virgin Islands in Congress, served as a House impeachment manager in the most recent impeachment trial of President Trump.

NEXT STORY: Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton Threatened to Sue Austin Over Mask Mandate. The City Isn't Backing Down.