Why New Jersey's Governor Started Memorializing Covid-19 Victims—and Won't Stop

Associated Press

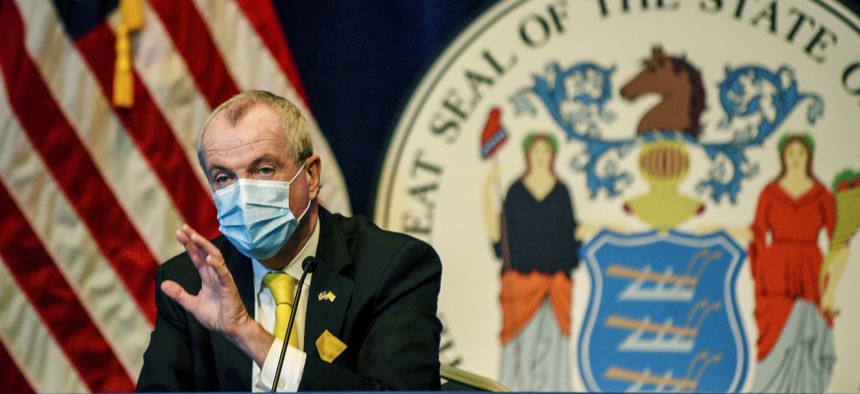

Since March 2020, Gov. Phil Murphy has used his Covid-19 briefings to eulogize residents who died from the virus, a practice he says is necessary to remember the humanity behind the data.

Roughly 14 minutes into his Dec. 18 daily briefing on Covid-19, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy paused. He’d just reiterated that vaccines had arrived in the state, but now had to recite a decidedly less positive list of numbers—44 newly confirmed deaths and 1,908 probable new deaths, bringing the state’s total to 16,216 casualties from Covid-19.

Nine months into the pandemic, Murphy tried to put the numbers in perspective. That many deaths, he said, is the same as erasing the population of the Borough of Rutherford, or Madison, or Hopewell Township, or any one of 417 other communities in the state.

“So many families know the ultimate pain of this virus,” he said. “And some families have had that pain magnified many times over. And this is one such family.”

As photos appeared on the screen next to him, Murphy named three men—Ahmad Shivwdayal, Jerry Seeraj and Altaf Seeraj, all Guyanese immigrants. Ahmad and Jerry were brothers-in-law, Murphy said, and Altaf was Jerry’s son. Last April, within a span of 12 days, all three died from Covid-19.

“Together, they showed that New Jersey is indeed the place where the American dreams of countless immigrants are realized,” Murphy said. “We thank them for being proud members of our family, and may God bless each of them, and watch over them, and their families that they now leave behind.”

It was one of hundreds of memorials that Murphy had included in a Covid-19 briefing, the then-daily press conferences held by governors across the country to keep residents apprised of the local status of the pandemic. Those presentations, necessarily, were rooted in data and science, and case counts and death tolls, but those objective metrics, Murphy felt, did not come close to telling the full story of the pandemic’s effect on his state.

“This is, at one level, all about the data,” he said. “We have to do that, because we have to make the decisions based on the data and the facts and not on some subjective guessing. But it struck me early on, like immediately, that if we did that, and stopped there, and did not talk about the humanity of this—the lives that were lived, the lives that were lost, the families left behind—that we would be underserving and disrespecting the loss of life.”

And so, beginning March 30, 2020, Murphy included details of New Jerseyans who had died from the virus. He spoke their names and told their stories during his televised briefings, and posted their photos and short biographies on social media. To date, he has publicly memorialized more than 500 people, a ritual that continues even as case counts and deaths decline.

“It’s for the same reason I started with,” Murphy said. “The numbers are the numbers, but the lives are the lives, whether they were lost last March or today.”

An Extended Family

A native of Guyana, Ahmad Shivwdayal first came to New Jersey in 1978 and found work at a metal finishing company in Newark. Jerry Seeraj made the same journey a year later; the two became friends, and Ahmad eventually introduced Jerry to his sister, Mesha. The two married, making Ahmad and Jerry brothers-in-law. Jerry and Mesha raised nine children, including Afzal Rahim (who goes by Mike Rahim), and Altaf.

The extended family—dozens of cousins, aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews—lived within miles of each other in Belleville, a New Jersey township near New York City with a strong Guyanese population. Altaf, who suffered from epilepsy, lived with Jerry and Mesha, and the three of them would get together with the couple’s other children several times per week, Rahim said.

Jerry and Mesha were germ-conscious even before the pandemic, Rahim said, so once Covid-19 was confirmed in New Jersey, the family took it seriously. They adhered to every public health recommendation at the time: frequent hand-washing, social distancing, wearing masks and leaving the house only when necessary.

For a while, the safeguards worked. Maybe, Jerry mused, this would be like previous ebola outbreaks—serious, but well contained, ultimately affecting only a small number of people.

But then worshipers at the family’s mosque tested positive for the virus. Several of them died. And days later, Rahim’s uncle Ahmad got sick.

And then Jerry began feeling ill.

He’d left the house for dialysis, he told Rahim, and developed chills a few days after. A fever followed, with body aches, sweating and dehydration. As Jerry, 79, grew sicker, Ahmad, 67, died in the hospital. Across town at his home, Rahim panicked, debating what to do.

“There are five people in my family and so I knew I couldn’t risk getting sick, but I didn’t want my mom or brother to get sick either,” he said. “I ended up going over there as often as I could just to check in on them. I told my mom to keep away from my dad as much as she could, and to keep Altaf away as much as she could.”

The family tried to care for Jerry at home, giving him fluids and vitamin C and over-the-counter medications. But he kept getting sicker, and finally, Rahim offered to take him to the hospital.

“And he said, ‘No, don’t come near me, just call the ambulance,’” he said. “I looked at him, and I knew that he knew that he wasn’t coming back. He kept saying, ‘Take care of your mom and brother.’ I said, ‘What do you mean? You’re going to be fine.’ That was the last time I saw him alive or spoke to him.”

The brothers-in-law died within three days of each other. Stunned, numb with grief and disbelief, the family held a wake for Jerry over Zoom. During the event, Altaf wandered through the background, stopping to console his mother.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” he said. “We’ll be OK.”

Days later, Altaf, too, became sick. Because of his epilepsy, severe temperature spikes put him at an increased risk of seizure, so Rahim drove him to the hospital.

“And here’s the thing—everyone kept going to the hospital and dying. Nobody was coming back,” Rahim said. “This time, I drove him there myself, and even when I dropped him off, I didn’t think he would succumb. We talked on the phone for hours after he was admitted. But he died the next night. He went on the ventilator, and I never talked to him again.”

No Time to Mourn

The loss would have been unimaginable in any circumstance, but saying goodbye to three family members in less than two weeks with no warning and no traditional mourning rites was inconceivable. Ahmad’s death was a gut punch, Rahim said, but there was no time to mourn; by the time Altaf died, 12 days later, reality felt impossible to process.

“I felt like people in a war zone, where you see dead bodies all the time,” he said. “The first one is awful, but after the second, third, fourth, you’re just numb. You don’t know what to say or do. People would send us sympathy cards and I didn’t know what to say. How do I say thanks? We were in a daze. We couldn’t believe what was happening. And it wasn’t just happening to us, it was happening to so many different people, across the state and the country.”

Unsure how to thank people individually, Rahim decided to offer a communitywide gesture of gratitude by hanging a banner in front of the family’s mosque. He called the city of Newark for permission, and when he explained his vision, officials there encouraged him to contact Murphy’s office.

“I was hesitant, but I thought if I called and told my story maybe they’d have a support center or some kind of resources for my mom,” he said. “So I called. And then they called back.”

'You Just See ... the Loss'

Bereaved families connect with Murphy’s office in a variety of ways, according to officials there. Sometimes the contact is a relative; other times it’s a coworker or a representative from a labor union. The submissions are vetted by employees in the constituent services office, who contact the families for permission to pass their information onto the governor. Murphy then calls each family to express his condolences, pass along his contact information and offer help in finding support services.

“They’re difficult calls, and some are more difficult than others—but the heck with whether they’re difficult for me. That’s not the point,” Murphy said. “You just see, live and in color, the loss.”

Rahim spoke to Murphy in December, days before the governor publicly memorialized his family members. The details of the conversation are hazy in his mind, though he remembers feeling astonished that Murphy had time to phone him directly.

“He was super nice, and at that time, people were dying by the thousands,” he said. “I can’t imagine what the governor was going through. I was saying to myself, the fact that this guy has time to speak to someone like me with all that’s going on, all this chaos—he’s not a bad guy.”

Back then, Murphy was largely isolated to protect the state’s continuity of government; his movements confined to quick drives to and from his office and his home. Beyond those phone calls offering condolences, there was no interaction with constituents. The comfort, it seemed, went both ways.

“At that point, they were literally, other than my family and a small amount of staff, the only interactions I was having,” Murphy said, then paused. “That point, I think, is very well taken.”

'They're Still Remembered'

As of Friday, 23,587 New Jerseyans had died from Covid-19, including Kathleen Eovino, a retired librarian memorialized by Murphy on Tuesday. Case counts continue to decline, and regular life seems, maybe, tangible, with vaccination rates climbing and restrictions, including size limits for gatherings, lifted.

In Belleville, Rahim and his family continue to heal. They hope to safely gather at some point this summer to properly celebrate Ahmad, Jerry and Altaf. The governor’s mention of his family members was nice, he said—“I’m happy that people knew them, and they’re still remembered”—but his hope is mostly that the story was able to offer solace to someone else experiencing similar loss.

“The only thing I thought my story would do is help people who experienced the same thing that I experienced,” he said. “It’s not me alone this is happening to, and maybe this could let someone else know that they’re not alone. There’s comfort in that.”

Kate Elizabeth Queram is a senior reporter for Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Many New Moms Get Kicked Off Medicaid 2 Months After Giving Birth. Illinois Will Change That.