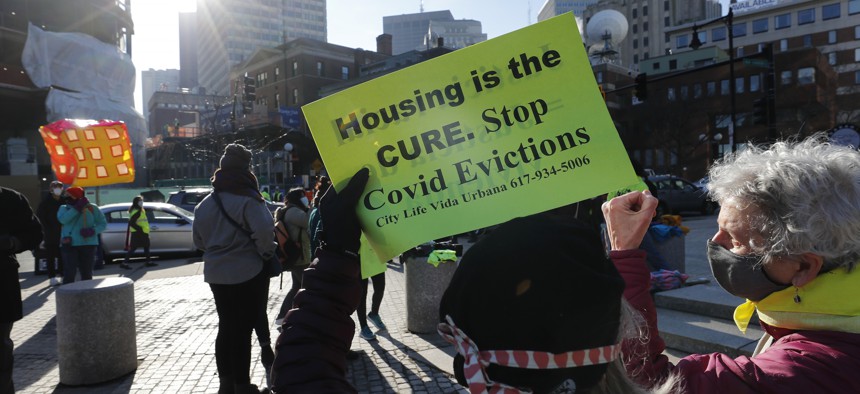

Cities and States Scramble to Get Aid to Renters as Federal Eviction Ban Nears Its End

Some states and localities are extending their eviction moratoriums as they try to distribute billions in federal rental assistance. When to let the bans lapse is a pressing question.

The federal eviction moratorium protecting millions of renters is set to expire at the end of June. With cities and states struggling to launch new rental assistance programs to provide tenants cash to pay overdue rent, some are opting to keep local moratoriums in place past the federal expiration date.

New York State, for example, just began accepting applications for its $2.7 billion rental assistance program on Tuesday. Meanwhile, the state extended its eviction moratorium through the end of August in order to provide protection for tenants while the aid is being distributed.

As local governments take action to prevent a wave of evictions later this year, it begs the question of when will be the right time to let eviction moratoriums expire.

“Most jurisdictions are not anticipating the federal moratorium will be extended,” said Samantha Batko, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute.

The CDC moratorium has provided protection for the more than 43 million renters across the country since September. Since then, estimates of how many people could potentially face evictions have varied along with unemployment rates.

Between 4 to 5 million households are at least three months behind on rent, putting them at a high risk of eviction when the moratorium expires, Batko said.

“That is not an insignificant number of households,” she said, adding that more people may be behind by less than three months but may still be unemployed.

The potential for a wave of evictions could be higher, depending on the actions of landlords and how quickly jurisdictions are able to distribute rent relief, she said.

How Long Should Eviction Bans Last?

Housing experts suggest that, like New York, jurisdictions should evaluate the functionality of their emergency rental relief programs before deciding to end eviction bans.

“The moratorium has to last long enough for the rental assistance program to do its job, and we don’t know how long that will be,” said John Pollock, coordinator for the National Right to Counsel, which advocates for legal representation for those facing evictions.

Congress has allocated nearly $47 billion in emergency rent relief through the Covid-19 aid legislation approved in December and March. But local jurisdictions have had to devise rent relief programs and mechanisms for doling out the money from scratch. And much like state unemployment agencies that were overrun by demand at the start of the pandemic, the rent relief programs have faced a similarly crushing demand.

More than 102,000 applications for rent relief have been submitted to the Texas Rent Relief Program. But the program had distributed 3%, or $37 million, of its $1.2 billion budget as of the end of April, according to a report from KSAT-TV. The program got off to a slow start, but officials there say they’ve increased staffing to help review applications.

“Whether the program is not doing it right, it’s just a massive challenge,” Pollock said.

Jurisdictions have had to craft eligibility rules for rent relief programs and find partner organizations to help spread the word about the programs to renters, housing experts said. That’s meant working to balance the need for quick distribution with including equity in the process “to make sure the people hardest hit by the pandemic are able to access these funds,” said Kim Johnson, a policy analyst with National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Landlords are not universally required to accept rent relief money, however. If landlords believe the programs will take too long to distribute money, they may opt to evict tenants rather than wait for relief payments to come through, experts said.

To address this, some jurisdictions have enacted legislation that would give tenants more leverage during the eviction process.

At least 11 states have introduced legislation this year that would establish “right to counsel” programs to ensure tenants have legal representation at eviction hearings. Nine cities have such programs in place.

Philadelphia has made it a requirement that landlords apply for rental assistance programs and go through an eviction diversion program before they are allowed to file eviction cases against their tenants.

Nevada lawmakers have introduced legislation that would temporarily pause evictions for nonpayment if the renter has a pending application for rental assistance.

The Problem for Local Governments

A wave of evictions would not only be problematic for those who lose their homes, but also the cities where they live, according to housing experts.

Homelessness is a growing problem across the country. But the costs associated with providing emergency shelter would likely skyrocket in the event of mass evictions, the National Low Income Housing Coalition predicted in a recent report.

The report, published in November, analyzed five costs of eviction-related homelessness to local governments and public agencies and estimated that if 6 million households were evicted, the total public cost to provide services to renters who became homeless would increase by $62 billion. Emergency shelter costs for six million households would comprise the bulk of the increase ($27 billion). Other expected costs would include inpatient medical care, emergency medical care, foster care, and juvenile delinquency.

“We all know how disruptive the eviction process is, but people will be evicted July 1,” Batko said. “It’s a matter of scale and how many people.”

The negative effect from large-scale evictions could create housing challenges for years to come, experts warn. Once someone is evicted, it becomes much more difficult for them to secure housing in the future, said Johnson, from the NLIHC.

“An eviction filing is a black mark on a tenant’s record and it makes it exponentially more difficult to find housing with that on your record,” Johnson said.

A ban on evictions isn’t the only way that municipalities can blunt the blow to affected tenants, she said. Jurisdictions can adopt legislation that would prevent evictions from being recorded in tenant history reports from March 2020 through the end of the pandemic, she said.

The extension of local eviction moratoriums are merely a “Band-Aid” on an otherwise much larger looming problem, Batko said. But where cities have extended moratoriums, they are buying themselves more time.

“It does provide the jurisdiction time to get the rental assistance program up and running before they are evicted rather than trying to rehouse a large number of people who have been evicted,” Batko said.

Andrea Noble is a reporter with Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: US Southwest, Already Parched, Sees ‘Virtual Water’ Drain Abroad