Autonomous Drones Could Speed Up Search and Rescue After Flash Floods, Hurricanes and Other Disasters

In this drone image released by NOAA, flood waters cover Tom's Marine & Salvage in Barataria, La., following the aftermath of Hurricane Ida. NOAA via AP

COMMENTARY | Drones that do not require individual pilots could cover ground quickly and identify people in need of help.

During hurricanes, flash flooding and other disasters, it can be extremely dangerous to send in first responders, even though people may badly need help.

Rescuers already use drones in some cases, but most require individual pilots who fly the unmanned aircraft by remote control. That limits how quickly rescuers can view an entire affected area, and it can delay aid from reaching victims.

Autonomous drones could cover more ground faster, especially if they could identify people in need and notify rescue teams.

My team and I at the University of Dayton Vision Lab have been designing these autonomous systems of the future to eventually help spot people who might be trapped by debris. Our multi-sensor technology mimics the behavior of human rescuers to look deeply at wide areas and quickly choose specific regions to focus on, examine more closely, and determine if anyone needs help.

The deep learning technology that we use mimics the structure and behavior of a human brain in processing the images captured by the 2-dimensional and 3D sensors embedded in the drones. It is able to process large amounts of data simultaneously to make decisions in real time.

Looking for an object in a chaotic scene

Disaster areas are often cluttered with downed trees, collapsed buildings, torn-up roads and other disarray that can make spotting victims in need of rescue very difficult. 3D lidar sensor technology, which uses light pulses, can detect objects hidden by overhanging trees.

My research team developed an artificial neural network system that could run in a computer onboard a drone. This system emulates some of the ways human vision works. It analyzes images captured by the drone’s sensors and communicates notable findings to human supervisors.

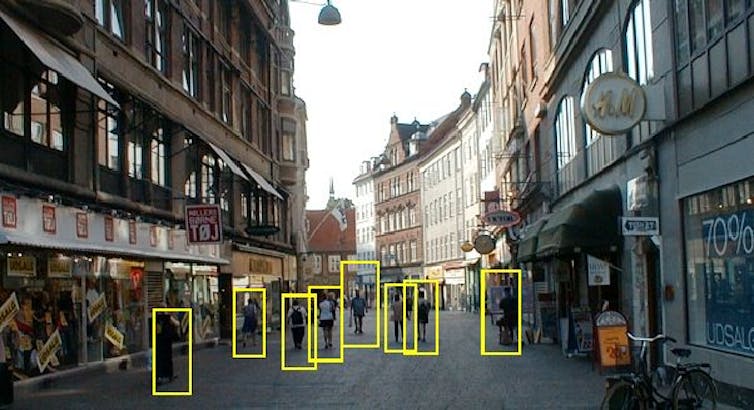

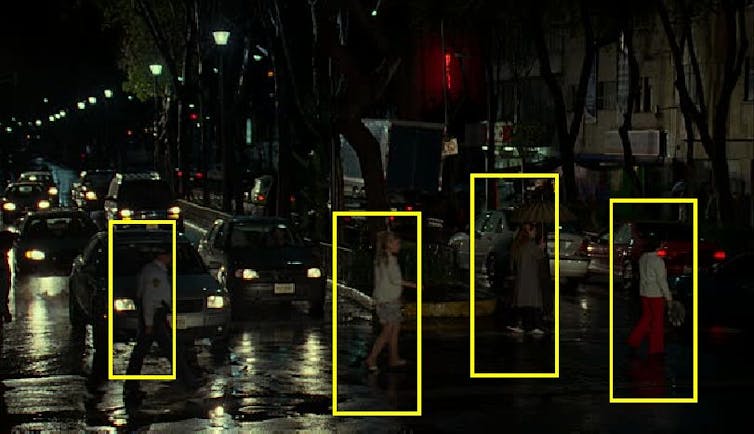

First, the system processes the images to improve their clarity. Just as humans squint their eyes to adjust their focus, this technology take detailed estimates of darker regions in a scene and computationally lightens the images.

In a rainy environment, human brains use a brilliant strategy to see clearly: By noticing the parts of a scene that don’t change as the raindrops fall, people can see reasonably well despite the rain. Our technology uses the same strategy, continuously investigating the contents of each location in a sequence of images to get clear information about the objects in that location.

Confirming objects of interest

When rescuers search for human beings trapped in disaster areas, the viewers’ minds imagine 3D views of how a person might appear in the scene. They should be able to detect the presence of a trapped human even if they haven’t seen someone in such a position before.

We employ this strategy by computing 3D models of people and rotating the shapes in all directions. We train the autonomous machine to perform exactly like a human rescuer does. That allows the system to identify people in various positions, such as lying prone or curled in the fetal position, even from different viewing angles and in varying lighting and weather conditions.

The system can also be trained to detect and locate a leg sticking out from under rubble, a hand waving at a distance, or a head popping up above a pile of wooden blocks. It can tell a person or animal apart from a tree, bush or vehicle.

Putting the pieces together

During its initial scan of the landscape, the system mimics the approach of an airborne spotter, examining the ground to find possible objects of interest or regions worth further examination, and then looking more closely. For example, an aircraft pilot who is looking for a truck on the ground would typically pay less attention to lakes, ponds, farm fields and playgrounds because trucks are less likely to be in those areas. The autonomous technology employs the same strategy to focus the search area to the most significant regions in the scene.

Then the system investigates each selected region to obtain information about the shape, structure and texture of objects there. When it detects a set of features that matches a human being or part of a human, it flags that location, collects GPS data and senses how far the person is from other objects to provide an exact location.

The entire process takes about one-fifth of a second.

This is what faster search-and-rescue operations can look like in the future. A next step will be to turn this technology into an integrated system that can be deployed for emergency response.

We previously worked with the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command on technology to find wounded individuals in a battlefield who need rescue. We also have adapted the technology to help utility companies monitor heavy equipment that could damage pipelines. These are just a few of the ways disaster responders, companies or even farmers could benefit from technology that can see as humans can see, especially in places humans can’t easily reach.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Vijayan Asari is a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Dayton.

NEXT STORY: Educators Want to Leave Their Jobs More Than Other Government Workers Do