Some States Are Cloaking Prison Covid Data

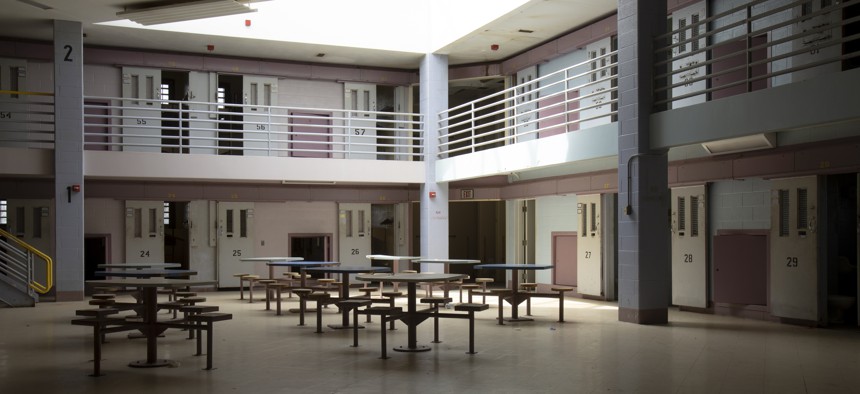

iStock.com/karenfoleyphotography

A half-dozen corrections agencies provide less detail than they did a year ago.

This story was originally posted by Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice maintains a public dashboard showing the status of COVID-19 in its prisons, including a tally of those who have died. Earlier this week, that number stood at 173 confirmed COVID-19 deaths.

The dashboard links to a list of names that ends with the Jan. 19 death of a 69-year-old serving a life sentence for murder, leaving the impression that no one has died of COVID-19 at a state prison since then.

But that’s not the case. Two incarcerated patients died Oct. 6, bringing the total COVID-19 deaths in state prisons to 295, according to the Texas Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that collects its data from reports sent by corrections officials to the attorney general.

Why the state reports one set of numbers to the public and another to its attorney general isn’t clear, said Eva Ruth Moravec, executive director of the Texas Justice Initiative. “It says where their priority is. If it was important to be transparent with the public, it would be on the public-facing dashboard.”

Texas is not the only state that has failed to consistently report COVID-19 cases and deaths in state prisons, local jails and juvenile detention facilities. While most corrections systems have never provided a great deal of information about the spread of the virus in their institutions, lately it has gotten worse, researchers say.

At least a half-dozen states, including Florida and Georgia as well as Texas, provide even less information than they once did, according to researchers at the University of California-Los Angeles’ COVID Behind Bars Data Project, which collects and analyzes data on the pandemic in corrections settings.

In an online post in late August, the project noted that while prison reporting had been “plagued by deep inadequacies” since the start of the pandemic, corrections systems cut back even more on public data in recent months. This happened even though prisons, like nursing homes, have been particularly susceptible to deadly outbreaks of the virus.

Agencies “had begun to roll back basic data reporting on the impact of COVID-19 in their facilities,” the authors wrote of a trend they detected beginning last spring. They characterize the drift as “a deliberate cloaking of the reality on the ground.”

States that have explained why they cut back on public data mostly say they stopped providing more detailed reports because of a decline in cases, even though they began making the change before this summer’s surge of the delta variant. Texas said its numbers are delayed because it waits for autopsy results, while Louisiana said the hours spent reporting data took time away from caring for patients.

The Behind Bars authors said the states have stopped publishing information on the number of cases, tests performed, deaths and vaccinations, both among inmates and staff. Some have stopped providing cumulative totals in those categories. Other researchers have found that hardly any prison systems publish demographic information, which would show the age, ethnicity and race of prison populations who have been the most vulnerable.

The UCLA project reported that in addition to Texas, prison systems in Florida, Louisiana, Georgia and Mississippi also have cut back on information that they had earlier provided about COVID-19 in their prisons. It noted that Arkansas has never disclosed the number of incarcerated people who have died of the virus. Meanwhile, the project observed that, like Texas, all those states were especially hard hit by the delta variant this summer.

‘Sort of Gave Up’

“I think probably there is a disincentive for them to report because the worse the pandemic deaths, the more it will be used against them,” said Erika Tyagi, a senior data scientist with the Behind Bars Data Project. “I think they thought, why are we giving data that the public will use against us? It’s bleak, but they sort of gave up.” Tyagi said Massachusetts and Oklahoma also have cut back on data reporting since the project published.

The Florida Department of Corrections did not respond directly to Stateline questions about its data, but it defended its treatment of sick patients and said all prisoners are offered vaccines. However, earlier this summer, the department acknowledged to the Orlando Sentinel that as of June 2 it had stopped posting weekly reports on COVID-19 cases and deaths among inmates and staff, determining that it was no longer “operationally necessary.”

In July, the Georgia Department of Corrections announced it was no longer reporting COVID-19 data on its website, citing a downturn of cases at the time. “Should significant fluctuations occur in the status of COVID-19 cases with our facilities, the dashboard will be reinstated,” Joan Heath, a department spokesperson, wrote in an email to Stateline.

In Texas, the public list of names from corrections officials indicates that zero incarcerated people died of COVID-19 from January through this month—even though nearly half of the total COVID-19 deaths among all Texans happened in that same period, as the highly contagious delta variant was running amok.

In response to a query from Stateline about the discrepancies between the number of deaths reported by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice and the number reported by the Texas Justice Initiative, agency spokesperson Robert Hurst said deaths were counted on the dashboard only after an autopsy or physician determined COVID-19 was the cause of death.

In addition to 173 confirmed COVID-19 deaths, the dashboard includes 34 presumed COVID-19 deaths and 64 with a pending cause as of Oct. 25. Hurst did not say why there has been a long delay in making those determinations this year. Even if the cause of those deaths were ultimately determined to be related to COVID-19, the department’s total would be well short of the number of deaths tracked by the Texas Justice Initiative.

In an email Hurst wrote, “The notion that TDCJ is hiding inmate deaths is ludicrous.”

Other researchers and advocates don’t accept that the state is simply waiting for autopsy results to disclose deaths.

“I don’t think anyone at all believes that,” said Michele Deitch, who runs the COVID, Corrections and Oversight Project at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas, which also tracks the reporting of COVID-19 data in prisons nationwide. “I think they’ve just stopped updating their numbers on the dashboard.”

Texas is not an outlier in terms of the amount of data it reports about COVID-19 in state prisons, Deitch said. Her team published a report in March showing that few states provide much data publicly. Only a handful of states received grades as high as B for their state prison reporting—California, Minnesota, Vermont, Washington and Wisconsin.

Most scored C’s and D’s. Because many states have cut back on their reporting since the scorecard was published, Deitch said many would now receive a failing grade.

As poor as the study found state prison data reporting, it concluded that transparency is even worse in city and county jails and in juvenile detention facilities. Hardly any COVID-19 information is available from those institutions, according to the report. Prison experts say data collection from jails and juvenile facilities is complicated by the higher rate of turnover in those institutions and a lack of resources. Deitch said jails also are generally subject to less oversight than state prisons.

The UCLA project also gave states letter grades based on the transparency of their COVID-19 state prison data. Nearly all of them scored D’s or F’s.

U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat, and others in Congress proposed a bill last year that would have required states as well as the federal government to collect and publicly report COVID-19 data from the prison systems they operate. The bill didn’t advance.

Corrections Dashboards

Some prison experts initially were surprised and pleased that within months of the pandemic’s onset, many state corrections systems began producing dashboards with at least some information about the progress of the virus in their prisons.

“Of course they should have, but the fact that they did it was particularly surprising in light of the fact that they typically don’t report much data about what happens inside,” Deitch said.

That’s why the recent rollback in information is so disappointing now, she said. Some prison systems probably thought the pandemic was over when they started curtailing the flow of information, Deitch said. But she also thinks some simply wanted to avoid scrutiny.

“A lot of this is that they felt they were being called out for the extensive spread of COVID in their facilities and extensive deaths, and many felt they could cut out the criticism by being less transparent with their data,” she said.

But critics said that thinking is short-sighted. Having complete and timely information, they say, would help officials track the progress of the disease and determine which efforts are most effective in combatting it. Demographic information would enable them to better protect vulnerable populations.

The data also is relevant to those outside facilities: to legislators and other watchdogs as well as surrounding communities, which, studies have found, can face higher levels of infections when there are severe outbreaks in corrections facilities. It also would help relatives of incarcerated people understand the risks facing their loved ones.

“The practical reality is the virus does not stop at the prison walls or jail doors,” said Corene Kendrick, deputy director of the ACLU National Prison Project. “You have staff going in and out of these facilities every day.” That gives the surrounding neighborhoods good reason to want to know what is going on with the virus behind the prison’s walls, she said.

The lack of transparency diminishes faith that corrections officials are effectively responding to the pandemic in those institutions, said Andrea Armstrong, a prison expert and professor at the Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. “Part of the value of publishing extensive data is assurance to the public and families of inmates that they are examining these trends and keeping on top of the infection and actively working to reduce outbreaks when they occur.”

Louisiana in July stripped down its prison COVID-19 dashboard to just the current number of active cases among staff and inmates at each prison. Before then, the Department of Public Safety and Corrections had published the number of people who had died from the virus and the cumulative number of cases.

Natalie LaBorde, executive counsel in the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections, said the state cut back on the information in part because the staff was too busy providing care to spend time collecting and reporting data. “That was adding two to three hours a day just reporting up to us,” taking away from time giving patient care to prisoners, she said.

Department spokesperson Ken Pastorick also said that in the two months before the department reduced the information provided, there had been only five new cases of COVID-19 among all prisoners. And, he said, the department was collecting all the data and could provide it upon request.

“That’s not what transparency means,” said Deitch in an email responding to Louisiana’s approach. “Most people don’t know how to request that information or are even aware that they could do so.”

She said policymakers, researchers and family members should be able to see the data in real time on a dashboard. “They don’t need to be jumping through hoops.”

Michael Ollove is a staff writer at Stateline.

NEXT STORY: College Towns Challenging Census Results After Pandemic Poses Count Problems