Using Rapid Drug Analysis to Reduce Opioid Overdose Deaths

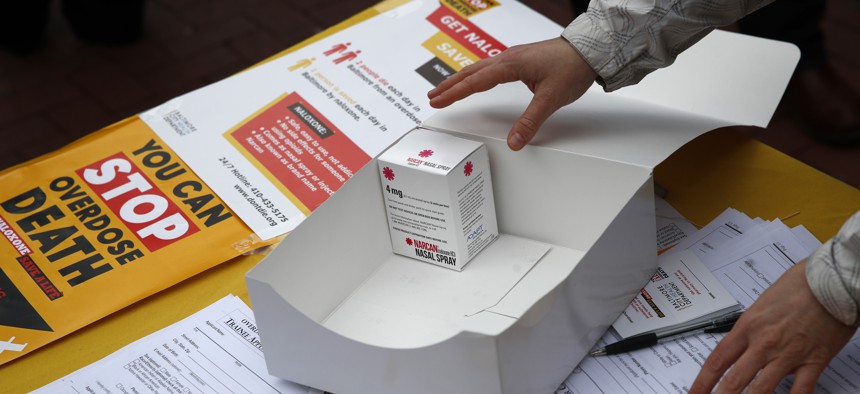

In this Jan. 23, 2018 photo, Kelleigh Eastman, a special projects director with the Baltimore City Health Department, reaches for a package of Narcan nasal spray in Baltimore. AP Photo/Patrick Semansky

A partnership between the Maryland State Police and Maryland Department of Health will allow for faster and broader testing of illicit drugs found in the state.

The highly potent and deadly drug fentanyl is increasingly showing up in batches of heroin, cocaine and counterfeit prescription drugs and driving overdose deaths across the country.

To better understand the composition and strength of illegal drugs being used and sold, Maryland law enforcement and harm reduction specialists are teaming up on a rapid drug testing pilot program that will allow them to analyze drug samples from across the state. By testing seized drugs and drug paraphernalia, officials hope to give law enforcement better insight into the state’s evolving illegal drug market and to give harm reduction specialists information they can share with drug users in a bid to prevent fatal overdoses.

“Until now, public health and public safety has been reactive in responding to this only after people die and we identify this substance in a toxicology report,” said Erin Russell, the chief of the Center for Harm Reduction Services at Maryland Department of Health, during a press conference announcing the program.

That process can take months. Meanwhile drugs tested as part of law enforcement investigations do not show the full picture because they often lack analysis of cutting agents that drugs are mixed with, Russell said in a subsequent interview.

Maryland’s rapid testing pilot takes a more proactive approach to drug monitoring and analysis. The pilot plans to process 100 drug samples a week and to provide weekly feedback about the drugs tested to participating harm reduction centers. The idea is that the centers, which regularly engage with drug users as part of needle exchange programs, will be able to provide information to users about what is showing up in the drugs bought and used in the region, Russell said.

During the first six months of 2021, Maryland recorded 1,358 unintentional drug and alcohol overdose deaths, according to the Department of Health. Of those, 1,129 deaths were linked to fentanyl, public health officials said. Roughly the same number of fatal overdoses (1,351 deaths) were reported during the same period in 2020.

Fentanyl is extremely potent and people who overdose on it often are unaware that it’s mixed with the drugs they consumed. The Drug Enforcement Administration recently warned that fentanyl is showing up in an increasing number of counterfeit prescription pills that are made to look like prescriptions sold on the street such as Adderall, Oxycodone or Xanax.

Opioid-related deaths rose 38% from January 2020 to January 2021 across the United States and fatal overdoses involving synthetic opioids (including fentanyl) are the primary driver of the increase, according to the DEA. More than 69,000 people died from opioid overdoses last year, with 57,500 deaths attributable to synthetic opioids.

Providing drug users with information about the composition of drugs they plan to consume has previously shown promising signs of preventing overdoses, Russell said. When drug users can use fentanyl test strips to find out if fentanyl is present in drugs they planned to consume, most users opt to do something differently when fentanyl is detected—from not consuming the drugs to taking a smaller dose, Russell said.

As part of Maryland’s pilot testing program, eight harm reduction programs that run needle exchange programs will serve as testing sites where drug samples will be collected from drug paraphernalia, Russell said. Some of the centers are run by local governments and others by nonprofits. The Department of Health trained staff on how to swab paraphernalia and collect samples, which are then mailed to a central lab where a direct analysis in real time mass spectrometer analyzes the samples. The department is still working through the best way to share its findings across the state, but expects to report back findings to the participating centers weekly.

The cost of running the pilot program is minimal, Russell said. The Maryland State Police has the spectrometer and the National Institute of Standards and Technology is donating the manpower to test and analyze the samples for the duration of the pilot. If the program continues past December, the state will have to find a way to pay for the testing, she said.

The findings of the pilot can help to tailor the state’s response to the opioid crisis, Russell said. Those responded could include more precise targeting of intervention services or distribution of Narcan, which is used to treat opioid overdoses.

Andrea Noble is a staff correspondent with Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: How Food Became the Perfect Beachhead for Gentrification