Election Officials Say Safety Threats May Drive Away Poll Workers

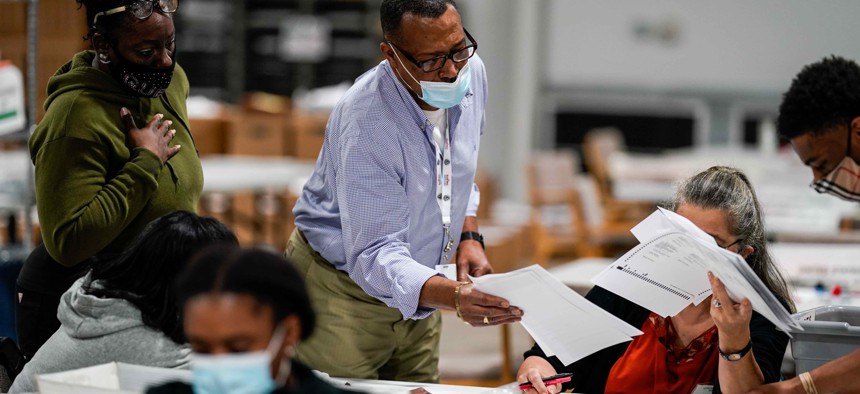

Election workers validate ballots at the Gwinnete County Elections Office on Nov. 6, 2020 in Lawrenceville, Georgia. Getty Images / Kent Nishimura

Three out of five administrators in a new study said they worried that threats, harassment and intimidation would make it harder to recruit new workers. Officials nationwide back that up.

Local election officials have long worried about whether they can find enough people to work in polls on Election Day. After all, the hours are long, the pay is low and, in recent years, workers have worried about the spread of Covid-19.

Now they’re worried a new phenomenon may keep workers away: threats to their physical safety.

Three out of every five respondents in a new Brennan Center for Justice survey of election officials said they were either “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” that “that threats, harassment and intimidation against local election officials will make it more difficult to retain or recruit election workers in future elections.”

The concerns about danger are part of the fall-out of the acrimonious 2020 presidential election. President Joe Biden clearly won the contest, but former President Donald Trump has fomented challenges based on conspiracy theories and riled up his followers to attack election administrators and workers.

“Counties organize about 800,000 volunteers each election cycle, and it’s getting harder and harder,” said Matthew Chase, the CEO and executive director of the National Association of Counties.

“During the pandemic, we struggled because a lot of our election volunteers were older and they certainly didn’t want to show up in the middle of pandemic and volunteer,” he said. “Now you layer on the harassment that they’re facing in the community for being a civic-minded individual, and we’re really concerned.”

Tammy Patrick, a senior advisor to the elections program at Democracy Fund and a former elections official in Maricopa County, Arizona, said the worries about whether workers will stay away because of potential harassment adds to a long list of potential problems that local officials must prepare for to ensure elections run smoothly.

“There are so many things that could cause grave concerns if they play out,” she said. “No one wants to ignore the [possibility] that they could play out, because we’ve seen what happens when we do. But we also don’t want to be so fixated on that negative possibility that we forget about all the other [beneficial things or things that need to be done.”

Lisa Hayes, the elections administrator in Guadalupe County, Texas, near San Antonio, said some of the county’s poll workers have expressed concern about the increased scrutiny that poll workers are under.

“What I tell them when we do our poll worker training is that we have always conducted our elections with integrity,” Hayes said. “We haven’t had to change the way we do our elections internally, because we have always [done] this as if everyone is watching us.”

“I try to reassure them that, as long as they are not intentionally intending to do harm, as long as they are not intentionally trying to commit fraud, as long as they are following our processes and procedures, that’s all we can ever do,” Hayes said. “That does seem to reassure them.”

Major Retention Issues

Kathy Morse, city clerk and treasurer in Rice Lake, Wisconsin, who oversees elections there, says 30 of the 45 to 50 people she had relied on for previous elections chose not to reapply in 2021. Luckily, her department has been able to recruit enough people to get the full list up to 27 people by late February.’

Having a larger roster to draw from is important, Morse said, because not all volunteers can work every election – and Wisconsin has a lot of elections. This year, it has four. Depending on the size of the election, they can require 17 to 35 election workers in Rice Lake, Morse said.

Extra hands are also useful, so that Morse can assign people tasks that best fit their skillset.

The partisan fallout from the 2020 election has been especially acrimonious in Wisconsin, where Biden prevailed by a margin of some 20,000 votes.

An investigation by Assembly Republicans into the process has dragged on, nearly 500 days after the election, and has not turned up any instances of fraud. Several mayors and local officials, though, have resisted orders from former state Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman to answer questions privately as part of the investigation.

But Morse said the main issue for retaining election workers in Wisconsin has been age, not public scrutiny. “A lot of [clerks] are having difficulty recruiting the next generation,” she said. That’s the case in Rice Lake, where many long-time volunteers are stepping back because of their age or because of Covid-related concerns, Morse added.

Patrick, from the Democracy Fund, said she hopes recent events, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, show Americans how important democracy is and what kind of work is required to maintain it. She is encouraged, she said, by the fact that so many people turned out to vote in the 2020 elections.

“I’m hopeful that my fellow Americans will not take our democracy for granted and [that they] will realize that if nobody signs up to be a poll worker, we don’t have elections,” she said. “If nobody runs for office to be a local election official or wants to be appointed or hired to be a local election official … our democracy dies.”

“A democracy is completely reliant upon people—not just voters, and not just candidates—but all the rest of us to make sure that it functions properly and is healthy,” she added.

Daniel C. Vock is a senior reporter at Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Curbing Violent Crime Through Place-based Policing