Coyotes Are Here to Stay in Cities. Here’s How to Appreciate Them From a Distance

Tim Karels via Getty Images

COMMENTARY | Though they can get a bad rap, coyotes often aren't as aggressive as many believe them to be. And in fact, they may bring some benefits to cities.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Coyotes have become practically ubiquitous across the lower 48 United States, and they’re increasingly turning up in cities. The draws are abundant food and green space in urban areas.

At first these appearances were novelties, like the hot summer day in 2007 when a coyote wandered into a Chicago Quiznos sub shop and jumped into the beverage cooler. Within a few years, however, coyote sightings became common in the Bronx and Manhattan. In 2021 a coyote strolled into a Los Angeles Catholic school classroom. They’re also appearing in Canadian cities.

People often fear for their own safety, or for their children or pets, when they learn about coyotes in their neighborhoods. But as an interdisciplinary team studying how people and coyotes interact in urban areas, we know that peaceful coexistence is possible – and that these creatures actually bring some benefits to cities.

Adaptable Animals

Coyotes can thrive in urban environments because they are incredibly adaptable. As omnivores, coyotes can change their diets depending on the type of food that’s available.

In rural areas coyotes may feed on bird eggs, rabbits, deer and a wide range of nonanimal matter, like plants and fruits. In urban environments they’ll supplement their natural diet with human-provided food sources, such as outdoor pet feeders and garbage cans.

Coyotes prefer to live in packs, and usually do so in rural areas. In urban areas, coyotes live in packs as well, although it may not seem that way because they are often seen individually rather than as a group.

Solitary coyotes not associated with a pack are somewhat common but tend to be transitory animals looking to join a pack or establish a new one in an unoccupied territory. These solitary coyotes can roam many miles per day, which enables them to disperse to new cities in search of food.

Some wild species need very specific types of habitat to survive. For example, the Kirtland’s warbler is a rare North American songbird that breeds only in young jack pine forests in Michigan, Wisconsin and Ontario. In contrast, coyotes are habitat generalists that can live on and around a wide variety of land types and covers.

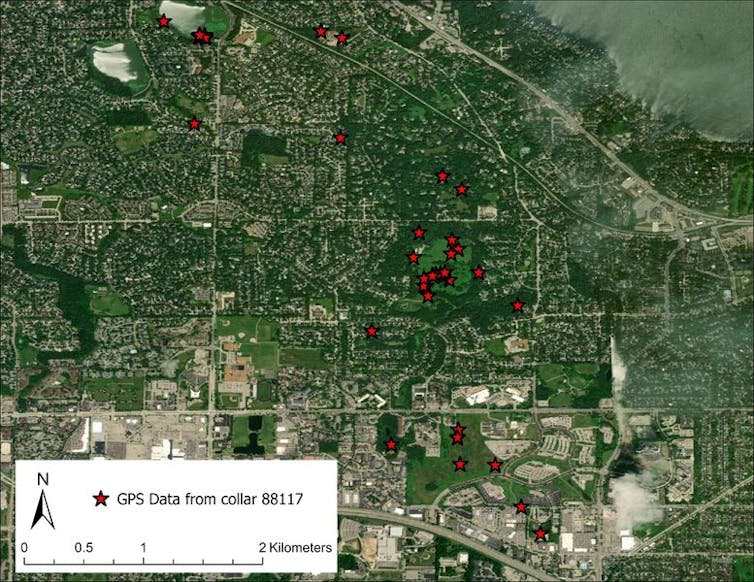

Many kinds of habitat that coyotes use in rural areas, such as parks, prairies, forest patches and wetlands, are also found in cities. Typically coyotes avoid the urban cores, but in Chicago they inhabit the downtown area and have been able to survive quite well.

Finally, urban coyotes have flexible activity patterns. Most urban coyotes are active mainly between dusk and dawn, when they are less visible than in daylight. However, as coyotes grow used to humans and begin to lose their fear of people, they may be seen more frequently during daylight hours.

Hunting Rodents and Spreading Seeds

Studies show that urban coyotes generally avoid direct interactions with people. A long-term study in Chicago found that these animals are good at adapting to human-built environments and navigating urban areas without being seen by humans. Often people may not realize they’re sharing the urban landscape with coyotes until they see one in their neighborhood.

Despite their trickster portrayal in folklore and popular media, coyotes tend to avoid conflict. They enter urban landscapes because they’re opportunistic. And because cities don’t have apex predators like wolves or bears, there are lots of smaller wild prey species, such as squirrels and rabbits, running around for coyotes to feed on.

A 2021 study conducted in Madison, Wisconsin, found that the vast majority of human interactions with coyotes there were benign. When asked to rank how aggressive coyotes had been during interactions on a scale of 0 (calm) to 5 (aggressive), most of the 398 people in the study chose zero. More than half of the coyotes in the study moved away from the human, indicating that the animals maintained a healthy fear of people.

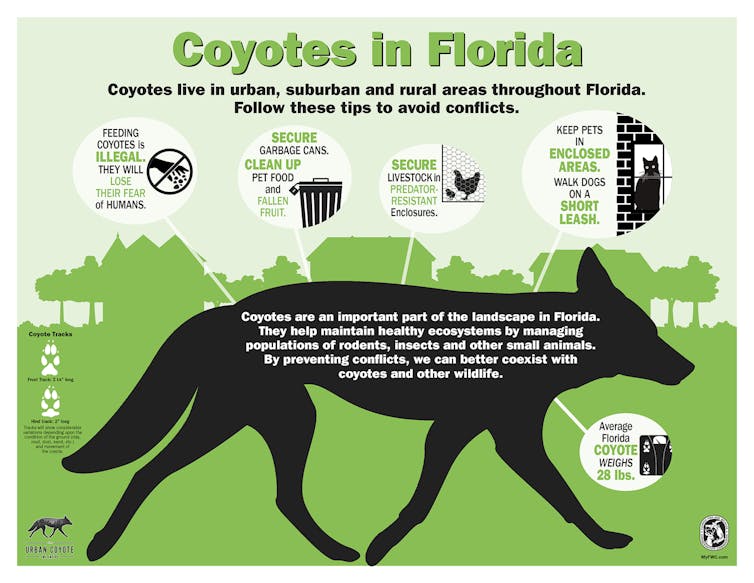

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

And having coyotes around can be useful. In urban areas they are at the top of the food chain and can help regulate populations of prey species such as rabbits, rats and mice. Since coyotes are omnivores, they also eat plant material and spread seeds when they defecate.

Our team is working to learn how people feel about coyotes in their urban communities so that we can identify the best ways to foster positive human-coyote relationships. In Madison, we’ve found that many people appreciate coyotes and are likely to respond positively to messages that highlight coyotes as a valued part of the urban landscape.

Don't be Afraid to Haze

If you encounter an urban coyote, it’s OK to enjoy watching it from a safe distance. But then haze it by making noise – for example, yelling and waving your arms to look big.

For animal lovers, this might seem harsh, but it’s extremely important to make sure the coyote doesn’t get too close. This teaches the animal to keep away from people. In the rare cases in which urban coyotes have attacked humans, the animals typically had become habituated to human presence over time.

If you have pets, keep them leashed in public parks and watch them when they’re loose in unfenced yards. Keep their food inside as well. To a coyote, a dishful of dog food is an easy free meal, and it may cause coyotes to revisit the area more frequently than they would if human-provided food weren’t accessible.

Based on existing research, we believe urban landscapes have plenty of room for coyotes and humans to coexist peacefully. It starts with each species giving the other enough room to go about its business. To learn more about these amazingly adaptable animals, check out the national nonprofit Project Coyote and the Wisconsin-based Urban Canid Project.

David Drake is a professor of forest and wildlife ecology and extension wildlife specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Bret Shaw is an associate professor of life sciences communication and Mary Magnuson is a master's student in environment and resources there.

NEXT STORY: The Debate Over Capping Drug Prices is Headed Towards the States