Cities and Towns Move to Recognize They are Built on Indigenous Land

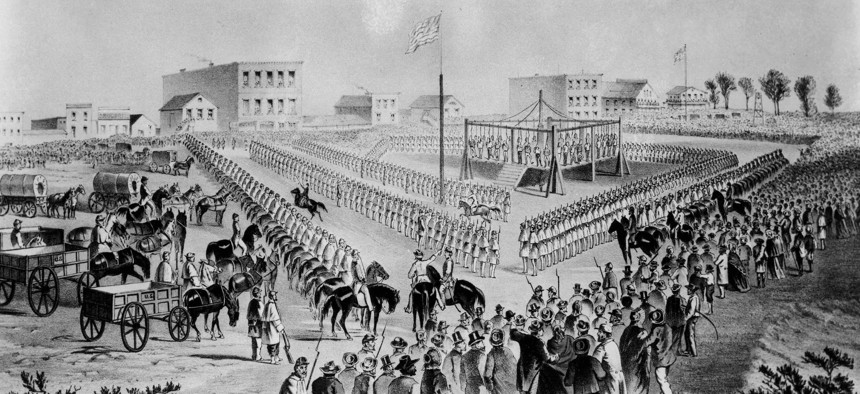

An illustration of the execution of 38 Native Americans in Mankato, Minnesota on Dec. 26, 1862. From 'Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper', Jan. 24, 1863. Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

But Native activists say "land acknowledgments" are only a start for reconciliation and healing, not an end unto themselves.

When Megan Schnitker, a Lakota woman from South Dakota, decided to move to Mankato, Minnesota about seven years ago, some of her older relatives were wary.

"My grandparents from Pine Ridge didn't want me to come here because of the history of Mankato,'' she recalled during a recent city council meeting.

This community of about 44,500 people, 80 miles southwest of Minneapolis, is home to a tragic episode in Minnesota's history: 38 Dakota men accused of engaging in a war with the U.S. were sentenced to death following a trial that historians say was unfair.

The men were hanged in Mankato before 4,000 spectators on Dec. 26, 1862 and, according to an account produced by the Minnesota Historical Society, their bodies were deposited in a shallow mass grave between the city's main street and the Minnesota River. It was the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

Now, Mankato, like other communities in Minnesota and across the nation, is coming to terms with its past.

A stretch of land along the river not far from the place where the massacre occurred has been reborn as Reconciliation Park; it features a monument listing the names of the 38 men who died there. In 2012, then-Gov. Mark Dayton apologized for the executions.

And last month, the Mankato city council adopted a land acknowledgment statement that formally recognizes that the city was built on indigenous land. The council also approved a guide that provides individuals with additional resources and will serve as a starting point for further education and reconciliation efforts.

Schnitker, who worked on the document and was in the audience on Aug. 8 when the council approved it, said she felt a surge of pride.

"It's moving,'' she told officials. "It feels like we're making giant leaps forward...so I just want to say thank you for the work that has been allowed to be done for the conversation to continue."

Dave Brave Heart, a Mankato resident who organizes the annual Mahkato Wacipi Pow-Wow, also found the statement meaningful. “One of the issues that we have in Indian Country is sometimes we feel invisible, so to really validate who we are...that's so important,’’ he told the city council.

The process of developing land acknowledgment statements began decades ago in Australia, New Zealand and Canada and has taken hold among U.S. academic and nonprofit organizations in recent years.

Institutions, including Princeton, Brown, the University of Illinois, Northwestern and the University of South Florida, have all adopted documents recognizing that they were founded on land where Native Americans once lived. Museums, government agencies and entities such as the organization that runs the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade have approved similar statements, which are typically read before meetings and events, or posted on official websites.

The movement is gaining ground in cities as well, with Boston, Denver, Phoenix and Portland, Oregon, among the communities approving indigenous land acknowledgements. Mankato joins at least three other cities in Minnesota—Northfield, Golden Valley and Eden Prairie—in endorsing such statements.

In their most basic form, land acknowledgments recognize the Native communities that once thrived in a specific city or region. Many statements also seek to uplift indigenous cultures and acknowledge the trauma caused by European settlers.

But such documents are starting points for reconciliation and healing, not an end unto themselves, said Wayne Ducheneaux II, executive director of the Native Governance Center, a Native-led nonprofit organization.

"Part of land acknowledgment is to really have folks take onus and responsibility to educate themselves about the place in which they live,’’ Ducheneaux said. "We think it’s a very valuable tool in order to get people to understand that truth because ...only by acknowledging the truth can you get to true reconciliation with somebody."

In 2019, the Native Governance Center published an online guide to indigenous land acknowledgement. Almost immediately, the organization was flooded with calls.

“We literally started fielding dozens and dozens of requests from people to have us write their land acknowledgment,’’ Ducheneaux said. The requesters ranged from a 5th-grade teacher in California to major corporations and large foundations.

"Because people were so focused on land acknowledgement, on getting the words right, we really quickly developed this concept that people need to go beyond land acknowledgement,’’ he said. “We want to make sure that folks are taking on that personal responsibility not only to learn for themselves but to make sure [they] create a society where this stuff becomes common knowledge.”

Understanding the truth about history and developing concrete strategies to work in solidarity with indigenous people are important steps in the process, Ducheneaux said. Anything less than that is “optical allyship,” an empty gesture that falls short of systemic change.

Specific actions can include things like ensuring representation of Native people on city boards and commissions, teaching accurate history that doesn’t skim over the brutality Europeans inflicted on indigenous people, or reparations.

“We really view the importance of moving beyond land acknowledgement as the key step in this,’’ Ducheneaux said.

“People shouldn’t get hung up on making sure every syllable of every sentence is correct," he added. "They should do good research and put out a statement that is meaningful to them and properly addresses the peoples whose land [they] occupy but then moving on to action steps: What can I do as an individual? What can we do as an organization to make sure we are moving toward a process of reconciliation?"

Officials in Mankato say they intend to work toward meaningful change. One step outlined by officials at the council meeting involved the possible renaming of city facilities to reflect the contributions of Native community members.

“The land acknowledgment recognizes that we are on indigenous land and it shows respect and acknowledges the Dakota people's past, present and future and the importance of their continued presence in our community,’’ Edell Fiedler, Mankato’s community engagement director, said at last month’s council meeting. “It helps further reconciliation efforts and educates others and encourages support of our local indigenous community."

Schnitker applauded that goal. “You’ve helped make my children feel very proud of themselves,’’ she said, “to wear their ribbon skirts in town, to feel able to speak their language that they’re learning and to feel proud to be from Mankato.’’

Daniela Altimari is a reporter at Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: A Library Struck by Controversy That Began Over a Book It Didn’t Own