States Grapple with the Death Penalty

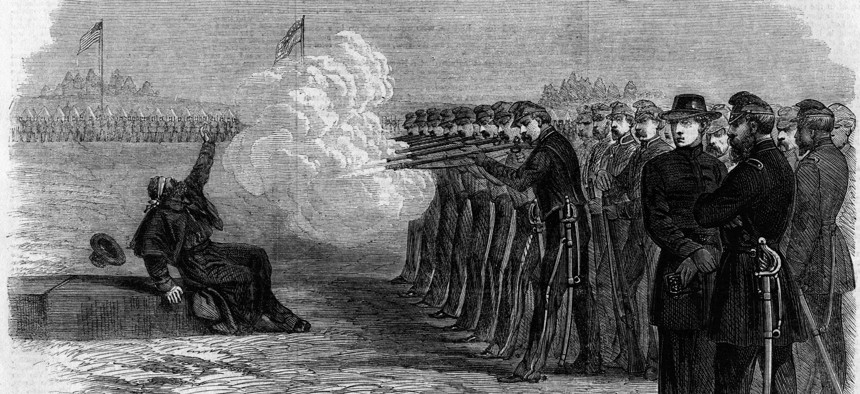

States that have had difficulty securing chemicals for lethal injections have turned to older methods of execution, such as authorizing firing squads that have been used by armies in conflicts like the Civil War. Kean Collection/Getty Images

As it becomes harder and harder to obtain the drugs involved in lethal injections, most states are pausing executions and others are turning to older methods, such as firing squads.

Idaho recently became the fifth state to allow for firing squads in the executions of prisoners sentenced to die. It was a last-ditch effort to keep the death penalty in place.

Like many states, Idaho is struggling to find the chemicals typically used to perform lethal injections because pharmaceutical companies are refusing to provide them.

The issue came to a head in December, when state officials delayed the scheduled killing of a 66-year-old prisoner who was convicted of two 1985 murders. It would have been the first lethal injection in Idaho in more than a decade. But prison system officials could not obtain pentobarbital, one of the drugs used in executions, despite a new law that shields the identity of the provider from public view. In February, prison officials delayed the execution again.

“I support policies that enable the state of Idaho to successfully carry out the death penalty,” Gov. Brad Little, a Republican, wrote to lawmakers after he signed the law. “I have not yet given up on the state’s ability to acquire the chemicals, and I believe the bill I signed into law last year [keeping the provider’s identity secret] helped expand options that would not have been available without it.”

But Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), said laws like Idaho’s show what a logistical and legal liability the death penalty has become, even in conservative states.

States can’t get the chemicals or trained medical personnel they need to administer them, he said. They have turned to prison staff who have little training. Last year, Arizona, Texas and Alabama all had botched executions within two days of each other. DPIC says seven of the 20 attempted executions in 2022 failed or were mishandled.

“Disaster has occurred,” Dieter said of those bungled executions. “They’ve had people on the gurney for hours, not dying, just being poked and prodded as [staff] attempt to insert a line into their veins … and then they give up. A couple of these executions never have gotten finished. It’s an embarrassment for the state.”

“As a result, they’re saying if they can’t get the people or the drugs, they’re going to go back to the electric chair or back to the firing squad or even back to the gas chamber. It’s a call of desperation,” he said.

Once a popular policy for tough-on-crime politicians, the death penalty has become increasingly rare. Nearly half of the states have no death penalty at all, and three more have moratoriums imposed by their governors. Only 13 of the 24 states that do have the death penalty on the books have carried out an execution in the last decade.

Not only are fewer executions being carried out, but fewer courts are imposing them. Only 20 people nationwide were sentenced to death last year, compared to 315 that were handed down at the height of the death penalty’s popularity in 1996.

Governors have contributed to the slowdown. Kay Ives of Alabama and Bill Lee of Tennessee paused executions in their states, following concerns about how they were administered.

Newly elected Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, resisted a move to go forward with an execution scheduled for April 6, and ultimately prevailed in the state’s highest court. Hobbs said the state wasn’t prepared to carry out the lethal injection following a lengthy execution last year, and she ordered a retired judge to review the state’s procedures.

“Under my administration, an execution will not occur until the people of Arizona can have confidence that the state is not violating the law in carrying out the gravest of penalties,” she said.

Arizona officials have also had trouble finding a source of pentobarbital.

In Louisiana, outgoing Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards spoke out against the death penalty in recent days, noting that the state has had more exonerations in the last two decades than executions. He said it was “fortuitous” that the state experienced a shortage of execution chemicals during his tenure.

In Oregon, then-Gov. Kate Brown commuted the sentences of everyone on death row during her last days in office in 2022. That came after the Department of Corrections had already dismantled the facility for condemned prisoners.

California has more prisoners sentenced to death than any other state, but Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a moratorium on executions and ordered the dismantling of the execution chamber at San Quentin State Prison last year.

“The intentional killing of another person is wrong and as governor, I will not oversee the execution of any individual,” Newsom explained at the time. “Our death penalty system has been, by all measures, a failure. It has discriminated against defendants who are mentally ill, Black and brown, or can’t afford expensive legal representation. It has provided no public safety benefit or value as a deterrent. It has wasted billions of taxpayer dollars. Most of all, the death penalty is absolute. It’s irreversible and irreparable in the event of human error.”

Meanwhile, states that have turned to different execution protocols have run into issues, as well.

Defense attorneys in Texas have attacked the state for repeatedly extending the use-by-dates of the pentobarbital it has on hand, claiming the older drugs lead to more painful deaths. A South Carolina judge ruled that using a firing squad or an electric chair violated the state constitution, in a case that’s now on appeal. In fact, only one state—Utah—has used firing squads in recent years.

“Many states are not willing to go back to these old methods,” said Dieter.

The procedures could run into legal trouble, because courts have traditionally determined whether penalties comply with the constitutional protections against “cruel and unusual punishment” by looking at current societal standards, he said.

Public opinion has shifted against the death penalty and those methods of execution, he added. That’s why the pharmaceutical companies have prohibited states from using their products for lethal injections. But it could also mean problems for bringing back older methods of execution.

“Some are passing laws to do that—the firing squad in Idaho, the electric chair in South Carolina,” he said. “But I don’t know how many brutal executions they’re going to carry out where the problems of lethal injection begin to look small compared to shooting somebody in front of their family and the victim’s family. That’s not exactly a badge of justice or something that I think is going to be popular.”

Daniel C. Vock is a senior reporter for Route Fifty based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: State & Local Roundup: Top Counties Return to Pre-pandemic Populations