New Data Sheds Light on Impact of Expanded SNAP Benefits on Households

Liu Guanguan/China News Service via Getty Images

A Census survey found that 1 in 4 households where enhanced food aid ended March 1 now report “sometimes” or “often” not having enough to eat.

As the country nears the official end of the national emergency prompted by the pandemic, the federal aid that lifted many families out of food insufficiency has also wound down, resulting in substantially smaller grocery budgets for some households. Enhanced benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, ended March 1, and a significant share of households are now reporting food insufficiency, according to a recent U.S. Census report.

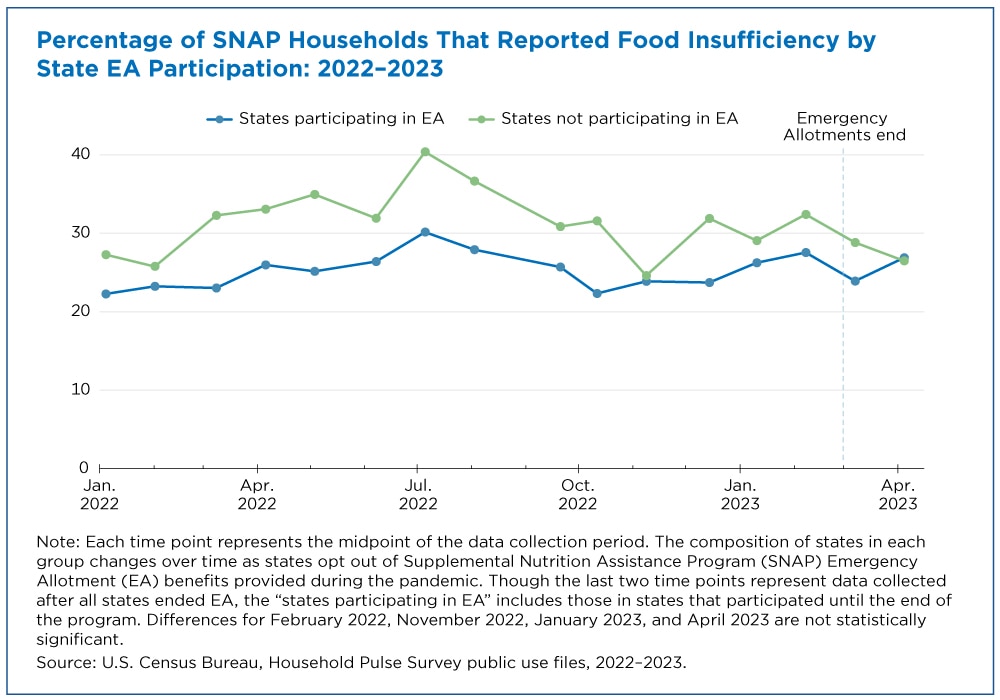

The latest data released last week marks the first full period of data collection since the end of enhanced SNAP benefits. It reveals that households in states that were distributing the extra benefits generally experienced lower levels of food insufficiency compared to those in states distributing standard SNAP amounts. Households in the states that opted out of emergency allotments early consistently reported “sometimes” or “often” not having enough food to eat at higher rates than those in states that continued to distribute additional SNAP benefits.

Now, 1 in 4 households in the 32 states impacted by the policy change are reporting they either “sometimes” or “often” do not have enough to eat. This level of food insufficiency is now “nearly identical” to the estimates in states that chose not to participate in the emergency allotment until its end.

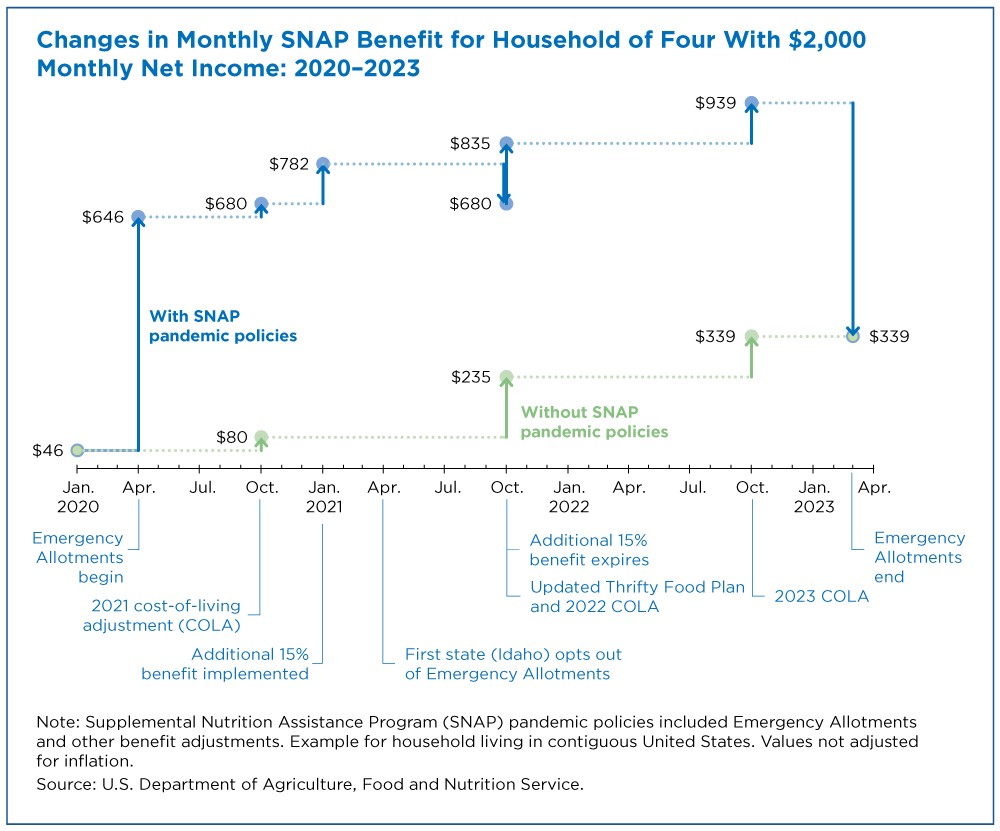

For some households that received benefits up until the program’s termination, the policy change has major implications. For instance, a family of four with a net monthly income of $2,000 received $939 more in SNAP benefits this year compared to before the pandemic began, the report said. With the end of the emergency allotments, that family is now receiving $600 less each month. In total, roughly 32 million people are receiving smaller monthly SNAP payments.

While all states were distributing emergency allotments of SNAP benefits by the end of 2020, 17 opted out of the program two years later, arguing that the enhanced benefits were contributing to the worker shortage. Households in those states were more likely to report food insufficiency than those living in states that administered enhanced benefits until recently.

“Though the long-term consequences of this policy change remain unclear, these data illustrate the role extra SNAP benefits played in providing recipients the resources necessary to meet their basic needs,” the report said.

The report uses data from the Household Pulse Survey which is administered by the U.S. Census and other federal agencies to understand the real-time social and economic effects of the pandemic.

In the period between March 29 and April 10, approximately 10% of adults nationwide reported not having enough food to eat, according to the survey. Some states saw even greater shares, including Mississippi (18.8%), Nevada (15.7) and Georgia (15.1%). At the other end of the spectrum, New Hampshire (4.4%), Minnesota (5.3%) and Vermont (6%) were the states with the smallest percentage of adults reporting they didn’t have enough to eat.

The survey also offers a look at food insufficiency in metropolitan areas. The Houston metropolitan area tops the list at 17%. Three California areas—Riverside, San Francisco and Los Angeles—appear in the top 10, but the other high-ranking cities are spread throughout the country, in Michigan, Georgia, Arizona, Florida and New York.

Many people have pointed to pandemic aid programs as the drivers behind poverty reduction nationwide in recent years. The expanded child tax credit was perhaps the most widely recognized factor in reducing childhood poverty, but SNAP seems to have played an important role as well. In a report published in August, the Urban Institute estimated that in the last quarter of 2021, the emergency allotments reduced poverty by 9.6%—which includes 4.2 million people—in states that were still distributing the expanded benefit. In those states, child poverty was reduced by 14%, and the rate among Black, non-Hispanic children was especially high at 18%.

Molly Bolan is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: New York To Ban Fossil Fuels in New Buildings. 23 States Have Forbidden Such Bans.