States Should Improve Opportunities for Older Youth in Foster Care Systems

Maskot via Getty Images

An Annie E. Casey Foundation report said more investments are needed toward job training, post-secondary education and stable housing for those in foster care between the ages of 14 and 21.

This story was first published by Maryland Matters. Read the original article here.

Since Tammy Young became a foster parent six years ago, she’s taken care of 35 children, including the five who reside at her home in St. Mary’s County, Maryland.

To support her foster children—ages 4, 6, 8, 9 and 16—it helps that Young receives a six-figure salary as a data architect with the U.S. Department of the Navy. A single mother of two adult children, she also has guardianship of a teenager who turned 18 in March.

Young said she receives support from the Maryland Department of Human Services for her foster children, but she acknowledged there remain problems with the state’s foster care system. Due to the high turnover rate amongst caseworkers, Young said she’s worked with numbers of people with varying degrees of experience.

“That is probably the biggest issue,” Young, president of her county’s Foster Parent Association, said in an interview Tuesday. “[The department] should do a survey with an outside company to assess what the issues are and how [caseworkers] can be enticed to stay.”

According to the state’s human services department, a foster care parent receives a monthly stipend between $887 to $1,024, based on the structure of care needed.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, which researches and advocates for policies to promote the well-being of youth and young adults, examined the state of foster care assistance across the country in a new report released Monday, “Fostering Youth Transitions 2023.” The report notes that some states have provided financial assistance for foster children and parents, but the foundation said more investments are needed toward job training, post-secondary education and stable housing.

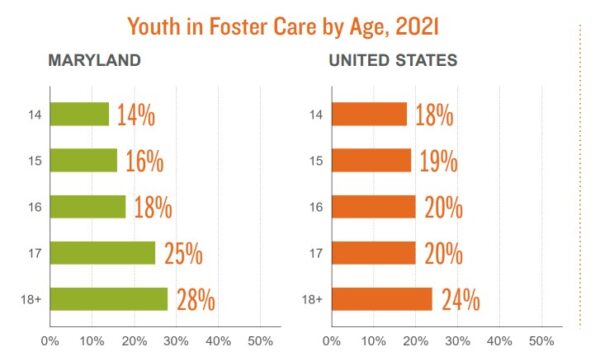

The report looked at issues including health insurance coverage, employment and educational achievement for those in foster care between the ages of 14 and 21. The report provides information from each state, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico and includes recommendations for federal and state policymakers to improve the foster care system.

Nationwide, neglect is the top reason why teenagers and young adults enter foster care, according to the report.

The dynamic is different—and has been changing—in Maryland.

In 2006, neglect was the reason 57% of older children and young adults went into Maryland foster care programs, compared to 29% in the nation overall. Fifteen years later, that percentage dropped to 37% in Maryland while neglect as a reason for entering foster care increased nationally to 48%.

Between 2006 and 2021, the population of older foster care youth in Maryland decreased by 62%. That tied with Pennsylvania for the 11th biggest decrease in the nation, according to the report. Another Maryland neighbor, the District of Columbia, saw the highest decrease at 84%.

But the racial and ethnic makeup of Maryland’s foster care population showed clear disparities in a state where, according to U.S. Census data, less than half of residents identify as white, nearly a third identify as Black and more than 11% identify as Hispanic/Latino. According to the report, Black children and young adults continue to count for a disproportionate share of those in foster care:

- Black youth accounted for 75% of the foster care population in 2006, and 60% in 2021.

- White youth made up 21% of the foster care population in 2006, and 23% in 2021.

- Latino youth represented 2% of the foster care population in 2006, and 9% in 2021.

The report outlined concerns that systems are failing to find permanent placements for young people in foster care, who experience lower rates of educational attainment and full-time employment than their peers.

About 27% of Black youth in Maryland remained in foster care on their 19th birthday in 2016. That percentage increased to 57% in 2021.

Post-secondary enrollment in education or training programs for those in foster care fluctuated during those years in Maryland and stood at 20% two years ago, compared to 24% nationwide. Enrollment among the general population of 21-years-olds in the U.S. was 50%.

“It’s clear from the data that states can do more to ensure that young people in foster care have permanent families and receive the services they need to thrive as they transition into adulthood,” Leslie Gross, director of the foundation’s Family Well-Being Strategy Group, said in a statement. “To achieve better outcomes, all decision makers who are designing solutions must authentically partner with young people who have foster care experience.”

‘Big job across the board’

Some of the recommendations in the foundation’s report are not only for policymakers but also to help advocates. They include:

- Addressing the rise in foster care cases attributed to neglect.

- Better equipping and staffing child welfare agencies to promote permanence and prioritize kinship arrangements for older youth.

- Improving services such as housing, post-secondary education and employment.

- Expanding child welfare agencies’ capacity and ability to collect, report “and strategically” use foster care data.

During this year’s Maryland General Assembly session, the Senate unanimously approved Senate Bill 359 that would’ve waived tuition or residency requirements at a community college for qualifying students including “a foster care recipient or an unaccompanied homeless youth.” However, the legislation died in the House Appropriations Committee.

But Senate Bill 848 will help some young adults still in foster care by establishing a statewide rental voucher program for eligible low-income families to receive housing assistance, including families with a foster child “at least 18 years old age but under the age of 24 years.” It goes into effect Oct. 1.

Democrat Sen. Guy Guzzone, who served as the bill’s lead sponsor, said in an interview Monday that staffing to help underserved youth remains a challenge with the state’s Department of Human Services. One reason for that, he said, is previous administrations either didn’t replace workers who retired, cut certain positions, or didn’t fill those were vacant.

“Foster care is one of them, but there are many parts of human services where we need to provide more staff,” he said. “In the full scheme of life, when you think about all the things we work on from children all the way through nursing homes, they’re not getting as much attention as they deserve. We’ve got a big job across the board in human services, but in all of government quite frankly.”

NEXT STORY: The Complications of Land-Use Reform