Digital Atlas Could Reveal Zoning's Social Impact

Francesco Scatena via Getty Images

An initiative to map out states’ zoning codes could help policymakers and citizens address urgent challenges in their communities.

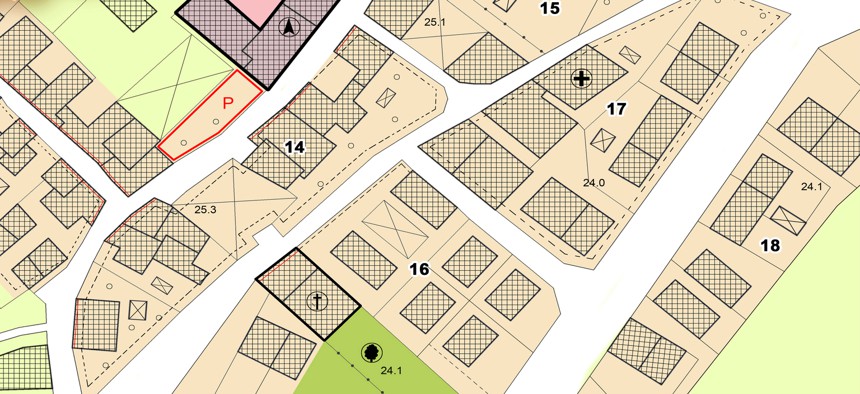

It’s no secret that historically zoning has contributed to a number of social problems, including segregation and neighborhood disinvestment. A new initiative seeks to reveal the extent of its role in racial discrimination by mapping out tens of thousands of zoning codes across states and regions.

By “digitizing, demystifying and democratizing” zoning codes, the National Zoning Atlas will give planners, housing experts and the broader public a more comprehensive understanding of what a state’s zoning landscape looks like, said Sara Bronin, the project’s director.

“We've used zoning to restrict opportunity, slow economic growth and destroy our environment,” Bronin said. “I think once people realize that that is the consequence of zoning as we have it, they will be much more willing to change it. In fact, they'll feel an imperative to change it.”

So far, only Connecticut, Montana and New Hampshire have completed zoning atlases. Efforts to create maps of land-use regulations are underway in about 20 other states.

In Montana, the statewide zoning atlas that went live this year helped inform a slew of housing bills that passed in April. Researchers with the Montana Zoning Atlas worked with a statewide housing task force to help lawmakers craft legislation to address the state’s housing shortage. The new laws ease regulations on duplexes and accessory dwelling units, create new requirements for local governments to update policies to meet projected demand, and limit parking requirements.

“There just wasn’t any data to show that zoning reform was needed,” said Kendall Cotton, director of the Montana Zoning Atlas, on a recent webinar. “We were able to provide that.”

Connecticut was the first state to create a zoning atlas in 2021, after the murder of George Floyd pushed advocates and officials to want to better understand links between structural racism and zoning.

Researchers manually reviewed more than 30,000 pages of zoning codes, which the Urban Institute used in a recent report analyzing the correlations between zoning codes and concentrations of residents by race, income and home value.

“These data are a real breakthrough and an advancement in the realm of understanding zoning’s influence over our lives,” said Lydia Lo, an Urban Institute researcher who worked on the report.

The tens of thousands of pages reviewed by researchers revealed that 91% of the state allows single-family homes to be built by-right, meaning without special permitting or hearings, while only 2% of the state allows for multifamily housing with similar ease.

In having data for the entire state, researchers were able to get a granular-level perspective of the zoning landscape and compare zoning regulations—and the associated demographics—across urban, suburban and rural areas.

They found, for example, that neighborhoods zoned for single-family homes are disproportionately whiter and higher income compared to multifamily neighborhoods. But in taking a closer look at jurisdictions, researchers found that single-family neighborhoods in the state's major cities are often much more diverse than multifamily neighborhoods in the state’s suburbs.

“Zoning is one part of the equation and certainly seems to be contributing to segregation,” said Yonah Freemark, a lead researcher for the Urban Institute. “But there are also some other trends at play,” such as the concentration of people of color and low-income people in cities. “That means that they're systematically not living in suburbs and towns throughout the state, no matter what the zoning background is.”

Lo says the report also found that when less than one-third of a jurisdiction’s land is dedicated to multifamily housing, it has significantly higher shares of white residents within their single-family zones compared to jurisdictions where a greater share of land is zoned for multifamily housing.

In discussions about zoning reform, Lo says, people are often quick to jump to the conclusion that eliminating single-family zoning is necessary to desegregate communities and bolster affordable housing. But that’s not necessarily the case. Instead, it’s important to focus on increasing the diversity of housing across all jurisdictions.

“What our research shows is that it's not necessarily single-family zoning that needs to go so much as we just need to be providing a greater diversity of housing types across all jurisdictions,” Lo said. “We can't just rely on center cities to provide that diversity of housing options.