States will soon be required to track post-welfare employment outcomes

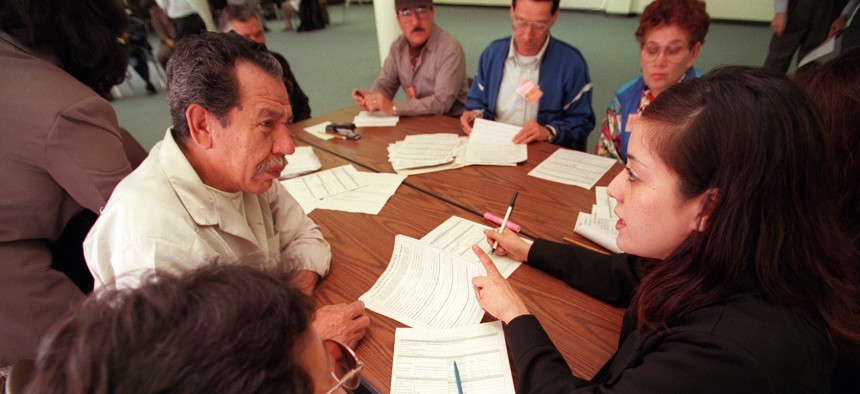

A county welfare official works with TANF recipients in a training session on improving job-seeking skills. Lawrence K. Ho/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

The new rule, part of the debt deal struck in June, is a bipartisan effort by Congress to improve welfare assistance and lift recipients out of poverty.

State welfare offices in a little more than a year will face the challenging task of having to keep track of how families do after they leave the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

Under the Fiscal Responsibility Act passed by Congress in June to keep the federal government from defaulting on its debt, states next October will be required to compile data on what percentage of people were able to find jobs between four and six months after exiting the program, as well as data on how much they are making at those jobs.

States will also have to track how many are still employed roughly nine months after they leave the program, according to an Urban Institute fact sheet alerting states to the new mandate. In addition, states will need to figure out how many of those 24 and younger were attending high school or working toward getting their GED while receiving assistance and how many graduated a year after exiting the program.

The requirement appears to be part of a bipartisan effort by Congress to get states to do a better job preparing welfare recipients for decent-paying jobs after they leave the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, program, said Heather Hahn, author of the fact sheet and associate vice president for management at the institute’s Center on Labor, Human Services and Population.

“It fits with interests on all sides of improving outcomes for people who are participating in TANF,” she said.

According to a report last year by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which examined 13 studies between 2007 and 2019, states haven’t been very successful at preparing welfare recipients to make a decent living.

The report found that in the states studied, between 60% to 80% of welfare recipients worked after leaving TANF. “But few worked steadily throughout that year,” according to the report. For the most part, they took jobs in low-paying sectors such as food service and child care, and did not make enough to “lift their family out of poverty.”

States vary widely in how they run the cash assistance program. For starters, the national cap for how long an individual or family can be on TANF is 60 months. Some states have shorter time limits. Arkansas, for example, only allows people to stay on welfare for 24 months. The state also has a lower income threshold. Families of three in Arkansas who begin making more than $696 a month are no longer eligible for TANF. In Illinois, meanwhile, the same family is able to stay in the program until they start earning $2,171 a month.

As a result, Hahn said, people who had to leave welfare in Illinois because they no longer met income requirements were more likely than those in Arkansas to be making a decent living. Illinois’ higher limit would make it appear that the state is more successfully preparing people to get higher-paying jobs, she said.

The new reporting requirements “could give an incentive to states to allow people to continue receiving assistance until they have higher incomes,” she added. That way when they do exit TANF, she explained, they’ll have higher incomes and the outcomes will look better.

Some states are already keeping track of this data. Welfare offices that are part of a state’s labor department will likely be able to more easily get the information, Hahn said. But those that are not will have to figure out how to keep track of whether people are employed and how much they make.

“Accessing earnings data for people who no longer have a connection to TANF is challenging, especially for the many state TANF programs that are not housed within the state’s labor agency,” the fact sheet said.

With the requirement starting on Oct. 1, 2024, Hahn said welfare agencies should be connecting with other agencies and offices in their state to figure out how “to collect the data that is needed for measuring those outcomes. And then also to think about, are there changes that they could make in their programs to better improve those outcomes,” Hahn said.

Meanwhile, states will also need to start preparing for another change that will go into effect a year after the data reporting requirement. Under a provision also included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act, many states will require more welfare recipients to work or be in job training in order to receive benefits.

Kery Murakami is a senior reporter for Route Fifty, covering Congress and federal policy. He can be reached at kmurakami@govexec.com. Follow @Kery_Murakami

NEXT STORY: You might need an ambulance, but your state might not see it as ‘essential’