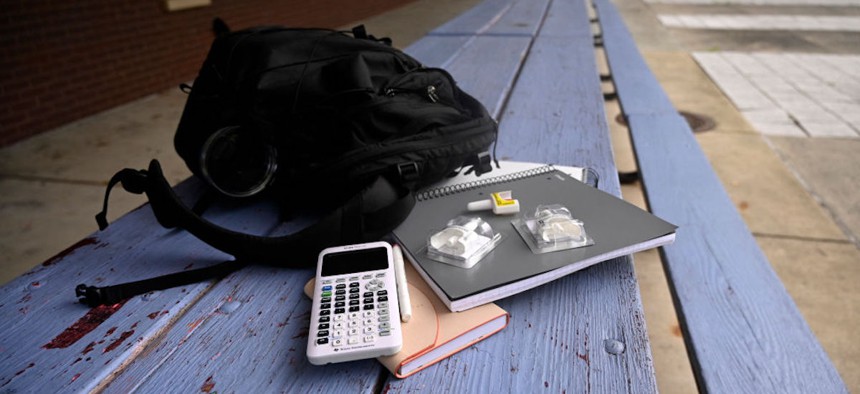

With youth overdose death rates soaring, state offers free opioid reversal medication to schools

OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images

The initiative comes amid a spike in the number of teens who have died from drug overdoses in the last five years.

This story is republished from the Oregon Capital Chronicle. Read the original article.

The Oregon Health Authority has turned its focus to the state’s skyrocketing rate of opioid overdoses among young people by offering free opioid reversal medication to schools.

The agency announced this week that it is expanding an initiative launched in 2020 that has distributed harm reduction supplies to more than 280 organizations and agencies statewide. This new emphasis by Save Lives Oregon focuses on middle schools, high schools, colleges and universities. The initiative is offering three free kits of naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal medication, to schools that serve children at least 7 years old. Each wall-mounted kit contains eight doses.

“The intent is to help school districts increase access to overdose reversal kits with their schools for use in the event of an opioid overdose emergency at or near a school campus,” a news release said.

The initiative comes amid a record rate of teen overdoses over the last five years. From 2018 through 2022, drug deaths among teens aged 15 to 19 soared 550% – the fastest-growing rate in the U.S., based on Centers for Disease Prevention and Control data compiled by a parent advocate, Jon Epstein. Over the same time period, nearly 300 people aged 15 to 24 died from a drug overdose – giving Oregon a higher death rate among young people than the national average.

Epstein and his wife, Jennifer, became involved in fighting drug use and overdoses among young people after their 18-year-old son Cal died in 2020 from counterfeit pills containing fentanyl. The drug, 50 times more potent than heroin, is driving the current epidemic. CDC data shows that all of teen drug deaths in 2022 involved synthetic opioids, or fentanyl.

Epstein, who combs through CDC data as part of his advocacy work, said naloxone “is not a silver bullet” because it doesn’t treat or prevent drug addiction. It’s only purpose is to keep people alive. But he said that might be all it takes to shock a teen away from drugs.

“We should absolutely have it in all schools, and if it’s free and easy to get this way, that’s fantastic,” Epstein said. “It should also be in every medicine cabinet and on every school bus.”

The medication needs to be easily available for quick application.

“Brain damage can occur within minutes of overdosing from fentanyl,” said Dr. Todd Korthuis, head of addiction medicine at Oregon Health & Science University. “Making naloxone available in schools decreases the time to reverse an overdose in teens who use fentanyl.”

The agency first offered the kits on Nov. 29, and so far more than 500 have requested them. They’re being paid for by up to $693,000 of the state’s opioid settlement funds, which were first distributed in 2022 and total $325 million over 18 years.

The teen drug rate outpaces that of all other age groups in Oregon. The second highest increase between 2018 and 2022 was 333% among those 70 to 74 years old, and the third highest increase was about 225% among those 30 to 34 and 40 to 44.

No Immediate Impact

Some school districts already have naloxone on hand, like the Beaverton School District. It has trained staff to administer the drug, which is often injected into a victim’s thigh or another large muscle. The district was the first statewide to launch classes for middle and high schoolers on the dangers of fentanyl. Senate Bill 238, which was proposed by Sen. Chris Gorsek of Gresham and passed by the Legislature, requires Oregon schools to adopt by next July similar curricula being developed by the Oregon Health Authority, State Board of Education and Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission.

Another measure, House Bill 2395, which was championed by Rep. Maxine Dexter of Portland and passed by lawmakers, aims to make naloxone more widely available. It includes a provision authorizing school administrators, teachers or staff to administer the drug to students experiencing an opioid overdose without written permission from the parent.

Although Epstein supports the initiative, he said more is needed than putting naloxone in schools.

“Schools are pretty safe places, but they’re not necessarily where kids are overdosing,” Epstein said. “In a school, it is like having an EpiPen, but it is not going to dramatically change the overdose death rate.”

Epstein wants the state to focus on “upstream” initiatives, like those recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They include reducing the availability of illicit drugs, awareness and education campaigns, harm reduction and mental health and addiction treatment.

“Raising awareness in schools about the life-threatening risks of fake pills containing fentanyl will help teens avoid unintentional exposure to fentanyl,” Korthuis said.