After a 7-year experiment, New Orleans is an all-charter district no more

Kindergarten students sit in a hallway at the charter school Benjamin Franklin Elementary Mathematics and Science in New Orleans, Louisiana. Mario Tama via Getty Images

The closely watched experiment is coming to an end. New Orleans Public Schools will now act both as a charter school authorizer and an old-fashioned school district.

This story first appeared at The 74. Read the original article here.

In August, New Orleans Public Schools will open a district-operated school named for Leah Chase, a late civil rights activist and revered matriarch of a culinary dynasty. The school will eventually serve 320 students from pre-K through eighth grade, with an emphasis on the city’s culture and history. Located in a historic building, it will replace the failing Lafayette Academy Charter School

As they hire Leah Chase’s teachers, pick its uniforms and curricula and arrange for transportation and lunches, district leaders are also creating the administrative jobs other school systems rely on to oversee individual buildings. These central office departments will make it easier for NOLA Public Schools to open more “direct-run” schools, Superintendent Avis Williams says.

You read that right: New Orleans’ love-it-or-hate-it, seven-year experiment as the nation’s first all-charter school system is coming to a close. Going forward, it will act both as a charter school authorizer and an old-fashioned school district.

In principle, the city’s charter school advocates are not opposed.

“I am personally governance-agnostic,” says Sabrina Pence, CEO of FirstLine Schools, which runs five schools in the city. “We wish the district every success in direct-running its first school in a while.”

Head of the Louisiana Public Charter School Association, Caroline Roemer says she is confident Leah Chase will be well run.

Tulane University professor Doug Harris, who produced numerous school improvement studies that helped shape the unique system, says the decision to create the infrastructure to direct-run schools will give the district flexibility to respond to unanticipated challenges.

NOLA Public Schools’ decision to return to running schools could be a game-changing inflection point in one of the most closely watched school-improvement efforts in history. After Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the city in 2005, the state of Louisiana seized control of most of the schools in what was then one of the lowest-performing districts in the country.

In the years that followed, the state Recovery School District created a totally new kind of system in which every school lived or died according to its performance contract. Schools that don’t meet those standards lose the charters that allow them to operate — an autonomy-for-accountability bargain that remains controversial even as it has led to better outcomes for students. The state returned New Orleans public schools to local control in 2016.

Two years ago, the Orleans Parish School Board appointed a new superintendent with a track record of success and no experience with charter schools. The board handed Avis Williams a formidable to-do list that included a dramatic downsizing to address enrollment losses and other sweeping decisions that would shape the next chapter of the school governance experiment. Progress has been halting.

In December, tensions surrounding the district’s future came to a head when Williams — under conflicting pressures from board members and seemingly without understanding the nuances of the system — decided not to renew Lafayette’s charter. What might in another moment have been missteps in timing and communications instead forced Williams’ hand on a number of consequential decisions.

Declaring charter schools a failed “experiment with children’s lives,” one school board member who had been pushing the district to return to a more traditional model demanded that Williams begin opening direct-run schools, starting with Leah Chase.

The architects of the grand experiment may not be opposed—but they are eager for answers to some big questions.

How will the prospect of opening new schools impact a lagging, three-year effort to address declining enrollment by closing others?

New Orleans faces a singular variation on a common problem. School systems throughout the country are facing the one-two punch of dramatic enrollment losses and the end of federal COVID recovery aid, forcing painful and overdue decisions about shuttering buildings and laying off staff. The politics of deciding how to meet the moment—playing out on steroids nationwide—is a frequent career-ender for superintendents and board members.

Locally elected school boards are easily overwhelmed by community ire and often either prolong the pain by taking piecemeal steps—such as closing two or three schools when there are 10 too many—or kick the can down the road by leaving the decisions for their successors. As resources dwindle in the remaining schools, student achievement typically falls, fueling further dips in enrollment.

By contrast, in New Orleans, an eight-year-old law—Act 91—spells out the process of replacing poorly performing schools with better ones. Under the law, the district authorizes individual charter schools, which may be operated by networks or standalone education groups.

When a school has underperformed for a certain period of time or has run afoul of financial or regulatory requirements, the district board must revoke its charter. The district can give the charter to another operator or simply close the school. The only way to deviate from the process is by vote of a supermajority of the Orleans Parish board.

But there is no provision for the board or superintendent to unilaterally decide to reduce the number of schools. Citywide, there are an estimated 4,000 empty seats.

In 2022, the nonprofit New Schools for New Orleans, which serves as a research and innovation hub for the system, warned school and district leaders that schools citywide were nearing a tipping point in terms of enrolling enough students to pay for a full array of academics and services. Post-Katrina, enrollment peaked in 2019 at 49,000, and by 2024 it had fallen by some 4,000 students, the organization’s analyses have shown. Birth rates are also in sharp decline, so the number of students will continue to drop in coming years.

Because almost all state and federal per-pupil funding in New Orleans is distributed according to enrollment, each school sets its own budget according to its ability to attract and retain students. Too many empty seats in any school, New Schools warned, directly impacts its ability to pay for the staff and programs needed to serve kids well.

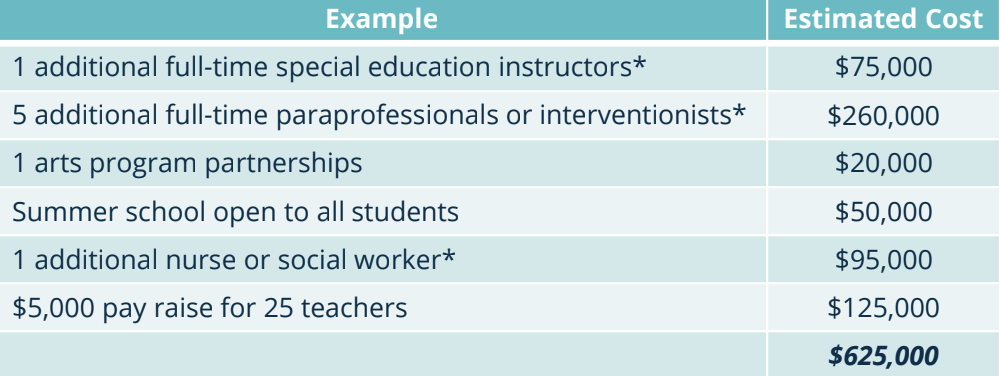

On average, last year, New Orleans’ K-8 schools had space for 550 students but enrolled 484, which equals a funding gap of $625,000. In its reports, New Schools has provided examples of the number of educators and programs that would have to be cut to make up that amount.

“You can’t drain resources out of schools five or 10 students at a time,” says Pence. “Lose 10 kids, that’s a teacher, maybe an art teacher—that’s always soul-crushing.”

After New Schools’s first report, Pence’s FirstLine was one of four charter networks that teamed up to consolidate six underenrolled schools into three buildings, eliminating 1,500 empty seats. The voluntary contraction required the charter school organizations to work together to figure out which schools were most accessible to families and which three networks would run the remaining schools.

Charter operator InspireNOLA merged two of its K-8 schools into one building, while ARISE Schools and Crescent City Schools combined a school from each network into a single building to be run by ASPIRE. The Collegiate Academies network merged two high schools, Rosenwald Collegiate Academy and Walter L. Cohen Prep, in Cohen’s brand-new building.

The district can reduce some excess capacity by closing underperforming schools instead of giving their charters to better-performing networks. But that alone would be unlikely to address the oversupply. Even if it could, the district needs a master plan to locate high-quality options in modernized buildings in every quadrant of the city. This means establishing how many schools should exist going forward, and how to make closure decisions that are not driven by school performance.

“There are questions of fairness,” says Harris. “Some neighborhoods don’t have good options.”

For example, a large swath of the city known as New Orleans East has lots of students but not many schools. “Performance is a good and important thing to start with, but you don’t want kids traveling 10 miles to school,” he notes. “You want high performers spread out around the city.”

What is to stop underperforming schools slated to lose their charters from lobbying to become direct-run schools?

New Orleans’s system was designed to insulate high-stakes closure decisions from political pressure. In 2015, Louisiana enacted a law spelling out limits on the Orleans Parish School Board’s power over charter schools and requiring it to step in when they underperform for long periods of time.

Legal parameters in place, the state returned the schools to the district. In 2017, NOLA Public Schools found charter operators for its last five traditional schools.

Since then, a small but vocal number of residents have demanded an end to charter schools in the district. A group called Erase the Board has routinely protested closures and backed school board candidates who agree that the state constitution requires the Orleans Parish School Board to operate like a conventional district.

They have an ally in state Sen. Joseph Bouie Jr., who has campaigned to overturn Act 91, the law codifying the district’s obligations to charter schools. For almost a decade, they had gotten little traction—not even after he equated the system to the Tuskegee syphilis experiment—with the exception of a change to state law to allow a board supermajority to overrule the superintendent’s recommendations.

Events of the last few months may, however, have allowed charter opponents to breach the firewall. When state report cards were released last fall, several New Orleans schools earned failing grades. In December, Williams recommended closing one and revoking the charters of two others, to be given to other operators.

By the board’s January meeting, though, no network had stepped up to run one of the schools losing its charter, the 500-student Lafayette Academy Charter School, so Williams recommended closing it. The board approved her request, but angrily.

In the past, to present an announcement about a closure or change in management with some certainty about families’ options, superintendents and charter network leaders would have talked beforehand about who should take over the charter and its building. Lafayette’s building was freshly renovated and in a desirable location, so normally the superintendent’s final recommendation to the board would have specified which of the district’s 67 schools should occupy it going forward.

Earlier, at that same board meeting, Williams had delivered a presentation explaining why the central office was not yet equipped to run traditional schools. To do so, districts typically need departments focused on things like curriculum and instruction, human resources, food service and other tasks performed independently by charter schools.

To pay for its responsibilities as a charter authorizer, NOLA Public Schools receives 2% of each school’s per-pupil funding, which is not enough to pay for the staff needed to oversee conventional schools. How this will be resolved is unclear, though most local leaders say there is no way the operation of a single school justifies the expense of creating the centralized infrastructure.

Unconvinced that the district could not simply open and run schools, the board’s new vice president, Leila Jacobs Eames, chastised the superintendent, saying she had asked repeatedly for the district to do so.

“It makes my blood boil to hear these excuses,” Jacobs Eames said. “As a superintendent, you really should have come with a plan to direct-run in your back pocket.”

Jacobs Eames also said it was time to end the all-charter district. “I am asking from you for a plan on future direct [run] schools” she railed. “This experiment with children’s lives has failed.”

Williams clapped back. She often gets requests from individual members, the superintendent said, but she needs clear marching orders from the board as a whole. Consequently, her highest priority has been creating the portfolio plan the board requested at the start of her tenure, outlining what the district should look like in the coming years.

“I do feel somewhat attacked by the suggestion I should have had [a plan to direct-run Lafayette] in my back pocket,” Williams replied. “Because at the end of the day, what I have had in my back pocket has been marching orders from the board that were very specific.”

Board President Katie Baudouin agreed, in part. “We have not, as a board, asked you for a plan for when, how and why you might direct-run a school,” she said. “We have been clear about the goals for district optimization.”

Finally, there was broad unhappiness with the district’s communications with families and board members about Lafayette’s future. Jacobs Eames was angry that she had learned about the closure several nights before, on the evening news.

A few days after the January meeting, the superintendent reversed herself, saying she would shutter Lafayette and ask the board in February to approve the opening of Leah Chase. By then, however, the deadline for the next year’s enrollment lottery was just days away, and neither the prospective new school nor Lafayette was an option.

Confusing communications about the transition, as well as its unfortunate timing, have reverberated among families, but the concern the charter community is left with is whether schools’ performance contracts can remain a chief driver of accountability.

“I’m afraid that what happened with [the Lafayette decision process] is it opens the door to the politics of closure,” says Roemer. “I get concerned that from now on, if a charter school is not operating at the level we want it to, the Orleans Parish School Board can step in and direct-run it.”

What happens now? How does the superintendent reshape a district still made up primarily of schools she doesn’t control — and hold the one she does to high standards?

In May, Williams previewed her developing district portfolio plan for the board, which is scheduled to see the comprehensive version in August. To date, it does not detail an optimal number of schools or map where they should be located.

Right now, half of New Orleans students attend a school that has an A or B rating on state report cards. Under the plan, the goal is for 80% to be enrolled in a high-performing school by 2028—a rate that must be reflected in every part of the community. At the same time, segregation and racial and economic disparities must be reduced.

Other factors, the superintendent said in an interview with The 74, include the need to offer a variety of curricular themes and models, such as Montessori and arts-focused programs, as well as contend with shifting demographics. The number of English learners in the city is increasing quickly, as is demand for offerings like language-immersion schools and programs focused on the arts.

“We do know that some of those models lend themselves to smaller classrooms or to schools being a certain size,” she said. “When we think of district optimization, it’s not a linear thing where all we consider is the number of seats.”

Any proposal for future direct-run schools will be considered against the same criteria and priorities outlined in the portfolio plan, Williams said. District-operated programs are subject to the state quality standards that govern all traditional Louisiana schools.

“I do see where people might be concerned, maybe even confused, about what this looks like for a district-run school in terms of accountability compared to charters,” she said. “But the accountability measures and standards will certainly be there. This includes financial audits and compliance monitoring for special education and for English learner services.”

Williams also acknowledged the concerns raised by creating a new direct-run school to replace a chronically underperforming charter. “It’s very similar to what’s happening now with the Leah Chase school,” she said. “It’s not the goal. I want us to be intentional and use data points to make those decisions and not as a workaround.”

Her goal is not to weaken accountability, Williams continued. “I also don’t expect this to be our answer to schools not on track to be renewed or schools that are not meeting the mark in terms of academic outcomes,” she said. “We’re dealing with children and families, and they deserve high-quality schools.”

Like other system leaders, Pence says she has no doubt this is the goal—and one shared by the city’s charter operators. “If the district wants to run schools, great, but we’re going to have to take some offline,” she says. “Closing schools, no matter what, is really hard. Everyone loves their school.”

Disclosure: The City Fund provides financial support to Collegiate Academies, New Schools for New Orleans and The 74.