Responding to post-pandemic norms, more states are lowering test standards

Eamonnn Fitzmaurice/The 74

The changes have renewed criticism of a testing "honesty gap" and have sparked calls for states to level with parents about poor student performance in the aftermath of COVID.

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education.

When an official with the Green Bay, Wisconsin, school district previewed new student test results for the school board last month, he urged members not to get too excited.

While it looked like the number of students scoring at the lowest level dropped by over 12%, the reality was more complicated.

“Comparing 2023 to 2024 is challenging,” David Johns, an associate superintendent, told the board. In conjunction with the unveiling of new standards last year, the state lowered its bar for proficiency and recalibrated performance levels. Below basic became “developing” and basic, “approaching.”

“It’s not exactly apples to oranges, but it’s like apples to apple juice,” he said.

Wisconsin isn’t the only state that recently instituted changes that effectively boost proficiency rates. Oklahoma and Alaska recently made similar adjustments. New York lowered passing or “cut” scores in reading and math last year, while Illinois and Colorado are considering such revisions.

Changing standards and proficiency targets is a routine process for states that some say offers a more accurate reflection of what students know. But given the cataclysmic effects of COVID on student learning, experts say now is not the time to tweak how we measure performance.

“Many parents are already underestimating the degree to which their children are lagging behind,” said Tom Kane, a Harvard researcher who has been tracking students’ recovery from COVID learning loss. “Lowering the proficiency cuts now will mislead them further.”

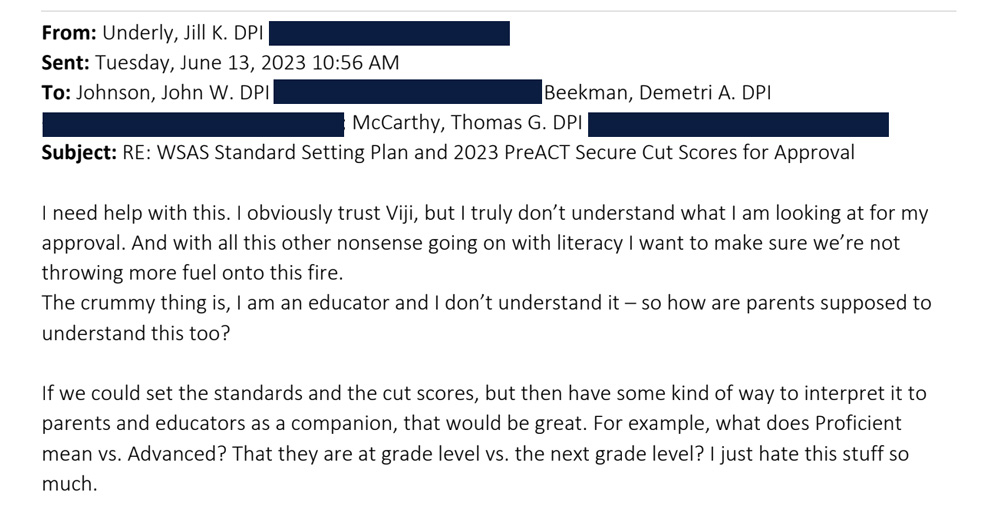

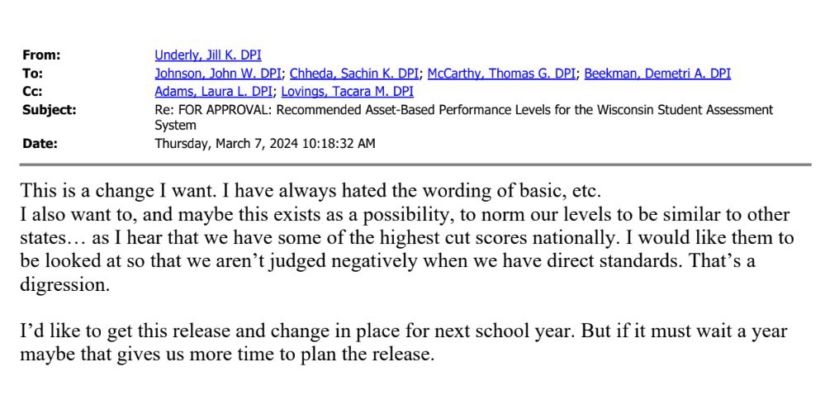

Even Jill Underly, Wisconsins’s education chief, confessed to some bewilderment about the process last year.

“The crummy thing is, I am an educator and I don’t understand it—so how are parents supposed to understand this too?” she wrote in a June 2023 email. “For example, what does Proficient mean vs. Advanced? That they are at grade level vs. the next grade level? I just hate this stuff so much.”

The conservative Institute for Reforming Government, which obtained the email through a public records request and shared it with The 74, is pushing the state to level with parents about poor student performance in the aftermath of COVID.

Shifting the goal posts “sends a message that we are accepting post-pandemic levels for student performance and shows a lack of belief in every student,” said Quinton Klabon, the think tank’s senior research director.

Chris Bucher, a spokesman for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, said Underly’s comments show she was “doing her job” by asking the department’s experts tough questions in an effort to make the complex calculations more transparent. To help explain the changes, the department released a summary of how it altered standards and cut scores.

‘An Outlier’

The scoring changes in Wisconsin and other states are likely to fuel fresh criticism of the “honesty gap”—the chasm between the disparate, conflicting measures states use to determine student progress and the more rigorous, uniform standard for proficiency set by the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Known as the Nation’s Report Card, NAEP defines proficiency as “solid academic performance” and “competency over challenging subject matter.” It’s a higher bar than merely being on grade level and one that has long triggered debate. Education researcher Tom Loveless, formerly with the Brookings Institution, calls it “pie-in-the-sky,” and one analysis of international tests showed that many students in high-performing countries couldn’t reach it.

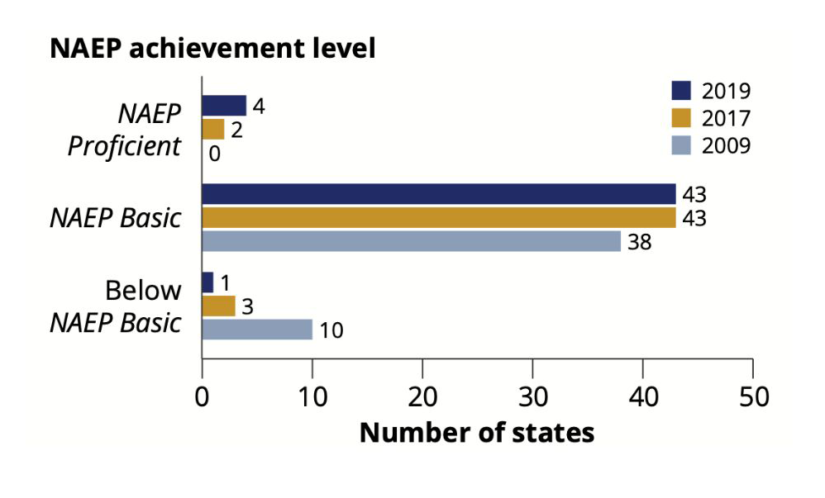

But it’s a goal many states were striving toward just prior to the pandemic, when several commentators first raised alarms about the “honesty gap,” and one some experts think states shouldn’t abandon.

“It is the only common yardstick that is available to compare student achievement across states and across the large urban districts,” said Lesley Muldoon, executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policy for NAEP. “From the board’s perspective, standards are not going to be lower for [kids] when they enter college or the world of work.”

Frustrated with shifting test standards in New York, Ashara Baker, a Rochester mother and state director of the National Parents Union, created her own report on student outcomes. While she included state data, broken down by race, she also cited NAEP proficiency rates as a comparison.

“When you’re lowering these cut scores, clearly the goal is to show some sort of growth,” she said. “But I think we’re getting away from the actual goal of why we do assessments. They should really demonstrate where kids are struggling or where there is a gap.”

Christy Hovanetz, a senior policy fellow at ExcelinEd, a think tank, added that unlike grades on assignments and homework, state assessments should provide parents “objective” information on how their children are doing. Schools also use them to determine which students are eligible for extra help. Lowering the bar, she said, means some students who need aid might not get it.

“These assessments are how we help identify students for extra support and assistance,” she said. “Now there will be a lot of kids that aren’t going to be getting those high-dosage tutoring sessions or who aren’t going to be getting that additional support in math that they might need.”

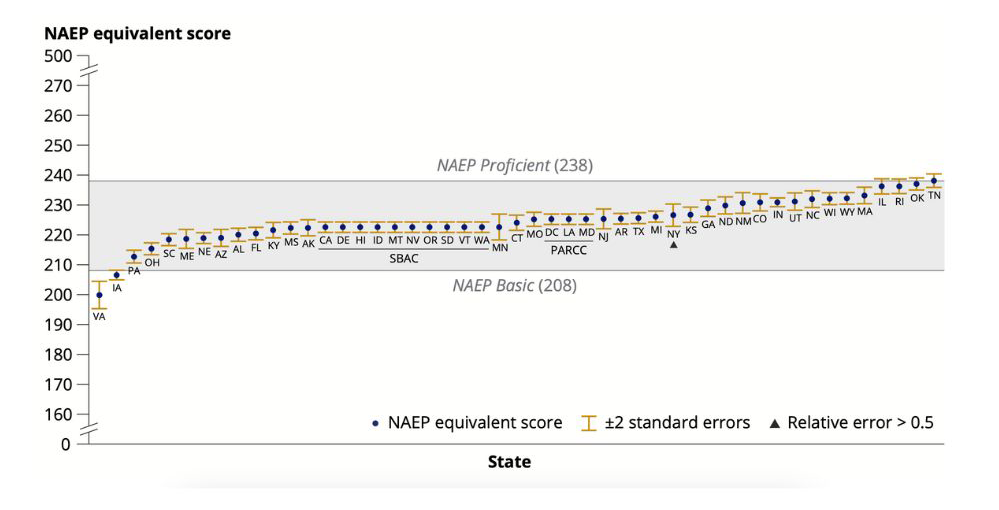

As with most states, New York’s threshold for proficiency lines up with NAEP’s basic level, defined as “partial mastery” of fundamental knowledge and skills, according to a 2021 report from the National Center for Education Statistics. The report showed that at the time, Wisconsin had some of the toughest standards for reading and math in the country, which meant that a higher percentage of students fell short compared with other states.

That made Wisconsin “an outlier” Bucher said.

“Our previous test scores made it appear kids were performing worse on standardized assessments than they actually were,” he said. “We listened to a group of experts—educators who are in the classroom each day teaching kids — who recommended we use cuts that align to our standards and take us closer to grade-level expectations.”

Next month, NCES is expected to update its 2021 report with a new comparison of states’ proficiency cut scores and NAEP, one that is likely to renew criticism of the way states measure student performance.

“States that have been more ambitious are now sticking out like sore thumbs,” Klabon said. “It’s kind of a race to the bare minimum, rather than a race to the top.”

‘A Sense of Urgency’

One state that is choosing to stick out is Virginia. Rather than calling it unrealistic, the state, under Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin, is hoping to reach the ambitious NAEP standard.

The governor drew attention to the honesty gap in 2022, announcing sweeping changes to the state’s testing regimen that include stricter standards, assessments and cut scores. A new school rating system, which takes effect in 2025-26, is expected to label a majority of schools off track or in need of “intensive support.”

“We are not telling parents, students, teachers, policymakers and citizens the truth about where our children really are on mastering content,” state education Secretary Aimee Guidera told The 74. “Why isn’t there a sense of urgency?”

The 2021 NCES report showed that Virginia had the lowest standards for proficiency in reading. Virginia education officials pin its poor showing on decisions made by previous Democratic governors. In 2014, under former Gov. Terry McAuliffe, the state passed a law requiring students to take fewer tests. And under former Gov. Ralph Northam, the State Board of Education lowered cut scores in reading and math.

Some critics accuse the Youngkin administration of fueling a negative perception of schools in order to promote private school choice, including education savings accounts, which failed in the state legislature last year.

Virginia saw the largest decline in the nation in fourth grade reading on the 2022 NAEP test, dropping from an average score of 224 to 214. But 32% of students were proficient—same as the national average. On several other measures, including the SAT and Advanced Placement exam, Virginia students have historically ranked near the top.

Advancing school choice was a “mandate for Youngkin and he has pursued it with dogged determination,” said Cheryl Binkley, president of 4PublicEducation, a Virginia advocacy group. He has appointed school choice advocates to the state board, she said, and pledged to increase the number of charter schools.

But Guidera points to increases in teacher pay and over $400 million the state provided to improve literacy as evidence that leaders aren’t trying to “tear down” public schools.

Under a different Republican administration in Oklahoma, the opposite scenario is playing out. As The 74 reported last month, the state education department, led by Superintendent Ryan Walters, made its state tests less challenging, especially in reading. In third grade, for example, 51% of students scored proficient or better, compared to 29% last year.

Richard Cobb, superintendent of the Mid-Del district, near Oklahoma City, said district leaders know student performance has improved, but the department’s changes had the effect of artificially inflating the magnitude of the gains.

The move represented a break from work led by Walters’s predecessor, Joy Hofmeister, to align the state with NAEP’s stronger proficiency targets. In 2017, over 70% of students on average were performing at the proficient level through elementary and middle school on state tests, but only a quarter went on to earn a competitive score on the ACT test in 11th grade.

“The whole idea was trying to get an honest indicator of student readiness as early as third grade when kids start testing,” said Maria D’Brot, a former deputy superintendent in Oklahoma who traveled across the state with Hofmeister to explain the honesty gap to local superintendents.

Their message wasn’t well received.

“Joy’s adjustment to the cut scores was wildly unpopular and demoralizing,” said Cobb, who has led the district since 2015. “NAEP should not be our target, and many superintendents told her that.”

But in the summer of 2017, 121 educators met at the Cox Convention Center in Oklahoma City to determine tougher cut points for each performance level. Just as Hofmeister warned the public, scores plummeted. The proficiency rate in third grade reading, for example, dropped from 72% to 39%.

Hofmeister, who was reelected in 2018, remains proud of that work, which she said would make students better prepared for college and a competitive job market.

“I remember feeling like this is worth it if it means I’m a one termer,” she said.