A Bolder Way To Tweet About Boulders: How A Traffic Alert Typo Rocked the Internet

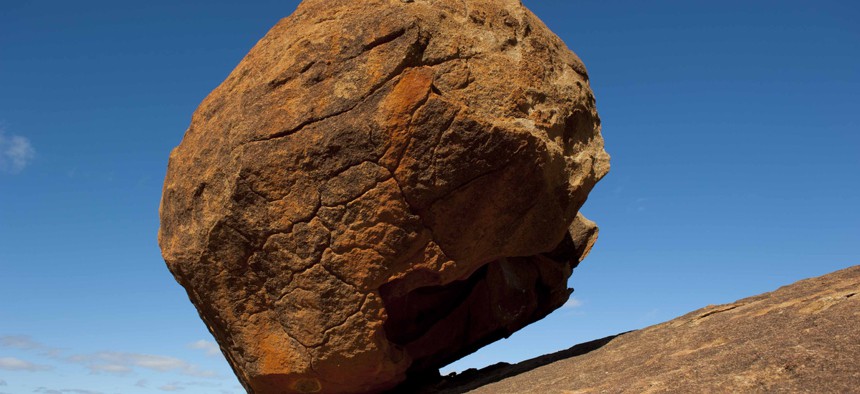

A stock photo of a boulder in Australia. It looks to be the size of a large boulder. Shutterstock

On Jan. 27, 2020, San Miguel, Colorado Sheriff's Office PIO Susan Lilly tweeted a warning of a highway obstruction: a "large boulder the size of a small boulder." The rest is internet history.

On the afternoon of Jan. 27, 2020, a dispatcher in San Miguel County, Colorado, made a simple request: could a deputy from the sheriff’s office confirm reports of a boulder blocking part of a highway?

Falling rocks are common in the county, where highways snake by ski resorts and through mountainous terrain. Most are small—the size of a book, or a basketball, or a toaster—but a few times a year, there’s a boulder big enough to stop traffic.

At her desk, Susan Lilly, public information officer for the San Miguel Sheriff’s Office, heard the call over the scanner. She got in touch with the deputy, who confirmed the rock was a big one.

“How big?” Lilly asked.

“It’s big,” he replied. “About the size of a small car.”

Lilly typed up an alert, listing the size and location of the rock. She attached a photo, gave it a quick proofread, and posted it to Twitter and Facebook. Shortly after, she got a call from the local radio station.

“They called and said, ‘So just how big is this boulder?’” Lilly said. “They weren’t kidding. There was nothing in their voice that led me to believe I’d made an error.”

Lilly called the deputy to get measurements (the boulder was about 4 feet in diameter) and logged back into Twitter to post an update. She noticed the alerts first, the ‘likes’ and retweets ticking into the hundreds. And then she saw it.

“And I said, ‘Oh, God,’” Lilly said. “‘Holy cow. What did I do?’”

--

A former television news producer, Lilly has served as the sheriff’s public information officer for seven years. Her main responsibility is to disseminate public safety and emergency information to San Miguel County’s 9,000 permanent residents, as well as the thousands of tourists who visit each year to ski and hike in the mountains.

“We’re just a typical law enforcement agency, dealing with anything that has to do with safety, and protecting the citizens and visitors,” she said. “It’s anything from a car accident, to search and rescue and traffic flow—plus the dynamic nature of the environment here. It just depends on the day.”

Social media is just one small part of that, Lilly said—another tool to distribute information. Growing that audience was never a priority for Lilly or the sheriff, and they’d certainly never brainstormed ways to go viral, or discussed what to do if it happened. That afternoon, watching her simple typo spread across the internet, Lilly ticked through her options.

“‘Do I delete the tweet? Do I leave it? Do I put out a correction? What do I do?’” she said. “And I decided, ‘you know what, it’s totally harmless, I’ll just leave it.’ And as I’m thinking this, the numbers were just skyrocketing.”

Decision made, Lilly picked up the phone to call her boss, Sheriff Bill Masters. Masters has his own Twitter account (dormant since 2017) and access to the main page, but doesn’t check either regularly. A dispatch call about a boulder—even a large one; even a large one the size of a small one—wouldn’t prompt him to log in, Lilly said.

“He was only going to know if I told him,” she said. “I called him and said, ‘Hey, by the way...we had this sort of innocuous incident. I made a mistake, and here’s what’s happening.’ I told him I thought I needed to leave it up, because I felt like taking it down at that point would cause more of a problem than it already was. He didn’t really care that I’d made the mistake and he basically deferred to my judgment.”

Lilly updated the sheriff a few more times—when the tweet hit 200,000 likes, when analytics showed that it had reached millions of people, when television stations began to call. A day later, with retweets and likes still accumulating, Lilly took to her personal Twitter account to take responsibility for the mistake.

“I am the author behind this now viral tweet,” she wrote. “I own my mistake, and now I rock it. #largeboulder”

The admission was less about personal infamy than professional obligation, she said. Most people seemed to enjoy the viral tweet, but a few had commented that leaving it up was unprofessional, and Lilly wanted to make sure the responsibility for the error stayed with her.

“I wanted to publicly take ownership for my individual mistake rather than have it be a blemish on the sheriff’s office, or on the sheriff himself,” she said.

--

That might have been the end of it, except the internet never really forgets, and so the tweet has never really stopped going viral. Every few weeks, it pops up again—via Reddit, or a new flurry of retweets, and, sometimes, in person. Last spring, for example, Lilly ran the communications operation for the county’s Covid response—and kept meeting people who recognized her name.

“They’d say, ‘Ah, you’re the large boulder county,’” she said “It’s just never really completely died.”

On Jan. 26, Lilly celebrated the typo’s first anniversary with another tweet (to date, it has more than 1,500 likes). Privately, she doesn’t quite understand why the original struck such a chord—but she’s grateful for the timing, if nothing else.

“I honestly never thought it was as funny as people thought it was. I’m amused now, I guess, but I’m not sure that I really get it,” she said. “But it has been a pleasant distraction for me in these times that are otherwise stressful, and if my mistake resulted in other people having comic relief, then that’s great.”

Still, she’s not entirely immune to the hilarity. On Feb. 5, dispatchers relayed a report of yet another boulder blocking highway traffic. This one was, unquestionably, large. Lilly knew what to do.

“I mean, it just fell on my lap, that one,” she said later. “I had some choices, but it just came to me that this was a large boulder the size of a large boulder, and that’s what I went with.”

Kate Elizabeth Queram is a staff correspondent for Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: After a Wave of Violent Threats Against Election Workers, Georgia Sees Few Arrests