Cloud Seeding Might Not Be as Promising as Drought-troubled States Hope

GettyImages/ Artinun Prekmoung / EyeEm

Several states are experimenting with weather modification to try to generate snow as water supplies shrink. An atmospheric scientist explains the history behind it and the challenges.

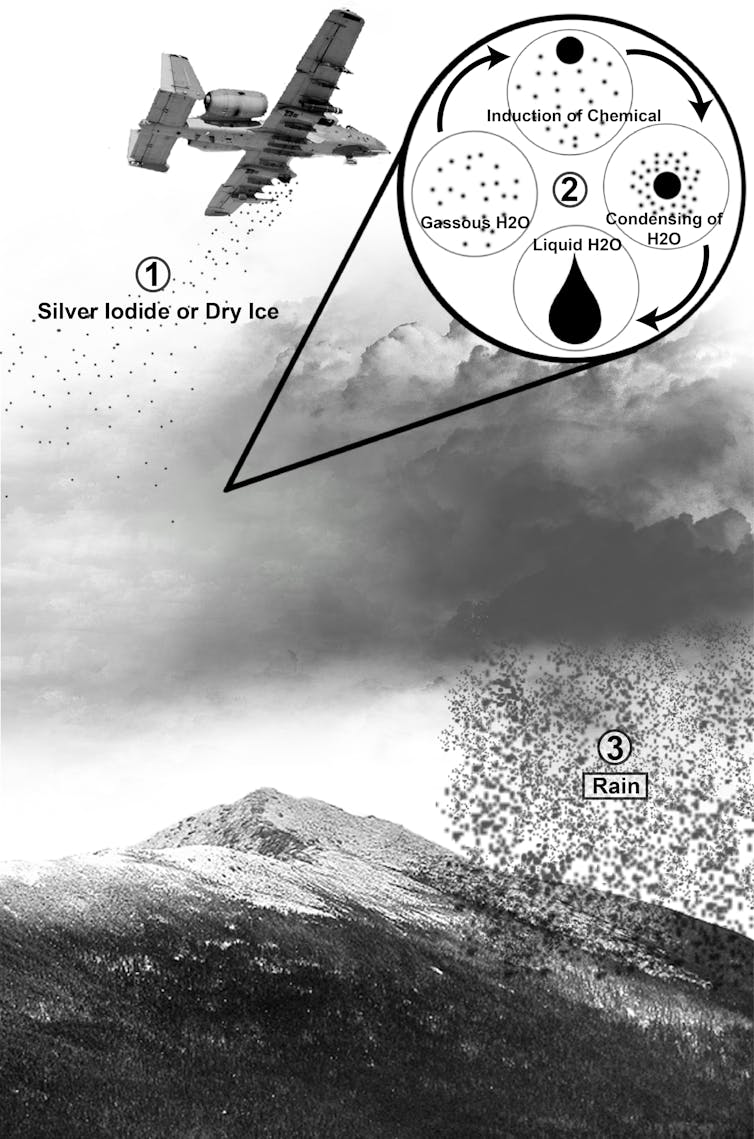

On mountain peaks scattered across Colorado, machines are set up to fire chemicals into the clouds in attempts to generate snow. The process is called cloud seeding, and as global temperatures rise, more countries and drought-troubled states are using it in sometimes desperate efforts to modify the weather.

But cloud seeding isn’t as simple as it sounds, and it might not be as promising as people wish.

As an atmospheric scientist, I have studied and written about weather modification for 50 years. Cloud seeding experiments that produce snow or rain require the right kind of clouds with enough moisture, and the right temperature and wind conditions. The percentage increases in precipitation are small, and it’s difficult to tell when snow or rain fell naturally and when it was triggered by seeding.

How modern cloud seeding began

The modern age of weather modification began in the 1940s in Schenectady, New York.

Vince Schaefer, a scientist working for General Electric, discovered that adding small pellets of dry ice to a freezer containing “supercooled” water droplets triggered a proliferation of ice crystals.

Other scientists had theorized that the right mix of supercooled water drops and ice crystals could cause precipitation. Snow forms when ice crystals in clouds stick together. If ice-forming particles could be added to clouds, the scientists reasoned, moisture that would otherwise evaporate might have a greater chance of falling. Schaefer proved it could work.

On Nov. 13, 1946, Schaefer dropped crushed dry ice from a plane into supercooled stratus clouds. “I looked toward the rear and was thrilled to see long streamers of snow falling from the base of the cloud through which we had just passed,” he wrote in his journal. A few days later, he wrote that trying the same technique appeared to have improved visibility in fog.

A colleague at GE, Bernie Vonnegut, searched through chemical tables for materials with a crystallographic structure similar to ice and discovered that a smoke of silver iodide particles could have the same effect at temperatures below -20 C (-4 F) as dry ice.

Their research led to Project Cirrus, a joint civilian-military program that explored seeding a variety of clouds, including supercooled stratus clouds, cumulus clouds and even hurricanes. Within a few years, communities and companies that rely on water were spending US$3 million to $5 million a year on cloud-seeding projects, particularly in the drought-troubled western U.S., according to congressional testimony in the early 1950s.

But does cloud seeding actually work?

The results of about 70 years of research into the effectiveness of cloud seeding are mixed.

Most scientific studies aimed at evaluating the effects of seeding cumulus clouds have shown little to no effect. However, the results of seeding wintertime orographic clouds – clouds that form as air rises over a mountain – have shown increases in precipitation.

There are two basic approaches to cloud seeding. One is to seed supercooled clouds with silver iodide or dry ice, causing ice crystals to grow, consume moisture from the cloud and fall as snow or rain. It might be shot into the clouds in rockets or sprayed from an airplane or mountaintop. The second involves warm clouds and hygroscopic materials like salt particles. These particles take on water vapor, becoming larger to fall faster.

The amount of snow or rain tied to cloud seeding has varied, with up to 14% reported in experiments in Australia. In the U.S., studies have found a few percentage points of increase in precipitation. In a 2020 study, scientists used radar to watch as 20 minutes of cloud seeding caused moisture inside clouds to thicken and fall. In all, about one-tenth of a millimeter of snow accumulated on the ground below in a little over an hour.

Another study, in 2015, used climate data and a six-year cloud-seeding experiment in the mountains of Wyoming to estimate that conditions there were right for cloud seeding about a quarter of the time from November to April. But the results likely would increase the snowpack by no more than about 1.5% for the season.

While encouraging, these experiments have by no means reached the level of significance that Schaefer and his colleagues had anticipated.

Weather modification is gaining interest again

Scientists today are continuing to carry out randomized seeding experiments to determine when cloud seeding enhances precipitation and by how much.

People have raised a few concerns about negative effects from cloud seeding, but those effects appear to be minor. Silver ion is a toxic heavy metal, but the amount of silver iodide in seeded snowpack is so small that extremely sensitive instrumentation must be used to detect its presence.

Meanwhile, extreme weather and droughts are increasing interest in weather modification.

The World Meteorological Organization reported in 2017 that weather modification programs, including suppressing crop-damaging hail and increasing rain and snowfall, were underway in more than 50 countries. My home state of Colorado has supported cloud-seeding operations for years. Regardless of the mixed evidence, many communities are counting on it to work.

[Get The Conversation’s best science and health coverage.]

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

William R. Cotton is a professor emeritus of meteorology at Colorado State University.

NEXT STORY: Lacking Mental Health Support, First Responders Turn to Peers