A Clash on Capitol Hill Over the Future of Utah’s Bears Ears Monument

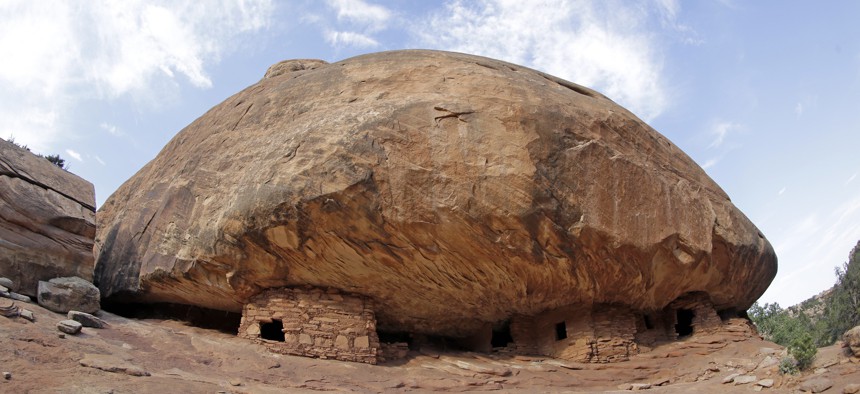

the "House on Fire" ruins in Mule Canyon, near Blanding, Utah, in the Bears Ears cultural landscape. AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File

Native American tribes are opposed to GOP legislation that would change the size and management of the Obama-era national monument, which President Trump has sought to shrink.

WASHINGTON — A coalition of five federally recognized Native American tribes staked out their opposition on Capitol Hill Tuesday to Republican-backed legislation that would codify into law drastically downsized boundaries for the Bears Ears National Monument in southeast Utah.

The tribes are taking this position even though GOP lawmakers say the bill would establish a council allowing for the first tribally co-managed national monument in the U.S.

“Nothing about this council is true tribal management,” Shaun Chapoose, a Ute tribal business committee member, who was speaking on behalf of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, told the House Natural Resources federal lands subcommittee.

“The council is a return to the 1800s, when the United States would divide tribes and pursue its own objectives by cherry-picking tribal members it wanted to negotiate with,” he added.

Chapoose said it should be up to sovereign tribal governments to select their representatives on the council. But under the framework in the bill, he pointed out, these appointees would be selected by the president in consultation with Utah lawmakers.

Using executive authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906, then-President Barack Obama established the 1.3 million-acre national monument in 2016 near the end of his time in office.

Its bounds encompassed red rock formations and pinyon-juniper forests, along with sites and artifacts that are culturally significant to Native Americans. The monument was forged from existing federal lands and did not involve the U.S. taking over private property.

President Trump in a proclamation last month called for downsizing the monument into two smaller parcels, which together equal about 201,000 acres. That move prompted legal challenges by conservation and tribal groups, who said Trump exceeded his legal powers.

But after Trump issued the proclamation, U.S. Rep. John Curtis, a Republican who hails from the congressional district where Bears Ears is located, introduced a bill that would establish revised boundaries for the monument akin to those in the president’s directive.

If enacted, the legislation would effectively render moot the lawsuits against Trump’s proclamation. This is because it’s generally accepted that Congress can alter monuments.

Utah Republicans in Congress and at the state and county level have strongly opposed Obama’s creation of the monument and characterize it as an example of executive overreach.

In the backdrop are long-standing frictions in the state over the federal government’s control of vast tracts of public land.

“We've had the public land dispute and Sagebrush Rebellions in the west for the last 100 years,” said Utah Gov. Gary Herbert, a Republican, who also testified on Tuesday.

Referring to the process by which the Obama White House established Bears Ears, Herbert acknowledged there was some consultation and dialogue between people in the state and the administration, but described it as inadequate.

The governor, who did not support the original monument designation, added: “we ended up having a dictator approach.” He called the original size of the monument “stunning” and said it is bigger than the state of Delaware.

Tuesday’s hearing marked the latest chapter in the messy debate about the future of the Bears Ears National Monument and what is, perhaps, the highest profile referendum at the moment about public lands in the west. The push to downsize Bears Ears has prompted blowback not only from environmental groups and tribes, but also from major outdoor retailers, such as Patagonia and REI.

“While it is difficult to overstate how politicized the creation and management of our national monuments has become,” Curtis said, “I believe all sides of this debate share many common goals.”

Republican lawmakers involved in the Bears Ears discussion insist that doing away with the Obama-designated monument boundaries is not a ploy to open up the area to oil and gas drilling or mining.

Curtis highlighted Tuesday that his bill would actually block these activities within the original 1.3 million acre area covered by Obama’s monument decree.

Meanwhile, House Natural Resources Committee chairman, Rep. Rob Bishop, also of Utah, raised questions about whether out of state conservation groups, that favored the monument, joined forces with tribes as an expedient way to lend credibility to their cause.

He introduced a 2016 news article into the meeting record on Tuesday to support this theory.

Chapoose rejected the case Bishop made. "I'm not a puppet,” he said. “I'm a tribal leader."

On the flip-side, Rep. Raul Grijalva, an Arizona Democrat, challenged a witness from the Sutherland Institute, a conservative Utah-based think tank involved in the Bears Ears debate, over whether the group had received financial backing affiliated with the Koch brothers.

“Sutherland Institute became engaged in this issue because we saw local voices being drowned out,” Matthew Anderson, who testified on behalf of the group, shot back.

Sitting beside Chapoose Tuesday was Suzette Morris, a White Mesa Ute community member who lives near the Bears Ears area. But she offered testimony in support of Curtis’s legislation.

“Our voices have been silenced by special interest groups funded by Hollywood actors, San Francisco boardrooms and by tribes who don’t live anywhere near Bears Ears,” she said.

But Chapoose bristled late in the hearing over who was speaking officially for the federally recognized tribes.

“The tribal leaders are sitting here right now,” he said. “The Navajo Nation president is seated right behind me.” He noted that although certain tribal communities don’t live in the immediate vicinity of the Bears Ears area today, it does not mean this was always the case.

“It’s not that we don’t live there. We were forced out of there,” Chapoose said.

Rep. Tom McClintock of California, who chairs the public lands subcommittee said at the end of Tuesday’s session that the panel would hold another hearing on Curtis’s legislation.

“The public lands issue is a complex issue,” noted Herbert, the Utah governor. “And most of the states of America don’t have the issue in their backyard.”

Bill Lucia is a Senior Reporter for Government Executive’s Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: CBO: 23 Million Americans Left Uninsured by House-passed AHCA