With More Money, States Weigh Expanded Tax Credits for Working Families

D. Pimborough / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

States are boosting earned income tax credits for working families as the Great Recession recedes and state finances improve.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Match the governor with the quote: Democrat Jerry Brown of California or Republican Charlie Baker of Massachusetts?

- “I have always liked the Earned Income Tax Credit because it doesn’t have any particular bureaucracy or complexity, it’s just a straight deliverance of funding to people who are working very hard and are earning very little money.”

- “You can debate all day how other supports work, but this one’s pretty clear: If you work a certain number of hours, and you qualify, you get the credit. I think that’s a good thing and I think we should do more of it.”

If you answered Brown for “A” and Baker for “B,” you are correct. But what’s striking is that these two governors from opposite ends of the country and representing different political parties are saying essentially the same thing: The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a good way to help working Americans, and the time to implement it (in California) or increase it (in Massachusetts) is now.

With the Great Recession in the rearview mirror for most states, several of them are enacting or enhancing the tax credit to help working families, especially, benefit at least a little from better financial times. Low-income earners are most likely to lag as the economy improves, and the EITC has proven to be a reliable source of help.

The EITC lowers the income tax bill of moderate- and low-income workers, boosting the amount of dollars they can spend on other things. Unlike an income tax deduction, it sometimes puts extra money in people’s pockets. It’s been a popular, bipartisan fixture of federal tax policy since its adoption in 1975 and has been copied in many states.

Liberals like it because it helps poor people narrow the income inequality gap. Conservatives like it because it rewards work.

“The EITC has for many years enjoyed bipartisan support,” said Michael Leachman, a research director for the progressive Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). “It’s been thoroughly studied and it really does help low-income families to make work pay.”

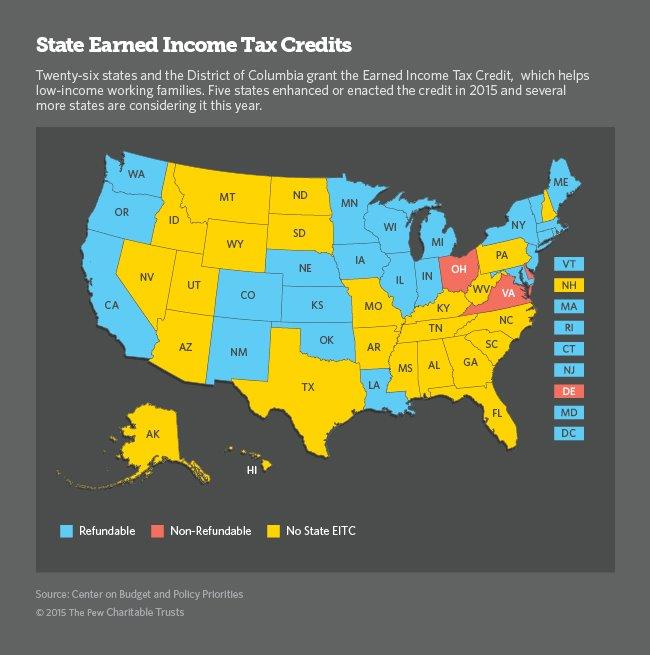

Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia now have an EITC. All but three of them make the tax refundable, which means filers who are eligible for a tax credit greater than their tax bill can receive the difference as a refund. For example, a filer who owed $800 in taxes and qualified for a $1,000 refundable credit would get a $200 refund.

So far this year, Massachusetts, California, New Jersey, Rhode Island and Maine have enacted or enhanced their EITCs. Michigan and Illinois are among the few other states still debating theirs.

Following the Feds

States generally set their EITCs as a percentage of the federal one, which offsets payroll and income taxes for people making between $14,590, for a single person with no children, and $52,427, for a married couple with three or more children.

Last year, 24.4 million taxpayers received $66 billion in EITC refunds from the IRS.About 10 million households benefited from state EITCs in 2014, according to CBPP. In 2015, that number will be increased by the new California credit and the credits in Colorado and Washington, which have been enacted but not implemented or funded.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the overall poverty rate in the country—16 percent—would have been 3 points higher in 2012 without the EITC and its companion, the federal Child Tax Credit.

In Massachusetts, Baker first called for a doubling of the state’s EITC last year, during his campaign for governor, from 15 to 30 percent of the federal credit.

“I heard a lot from people about making ends meet,” he said in a recent interview, citing the 400,000 Massachusetts residents who would benefit from the credit. “All those people are still paying Social Security tax. It’s a tax credit, sure, but it’s also an offset against other taxes they pay anyway.”

Baker wanted to pay for doubling the credit by phasing out the state’s embattled film tax credit. But the Democratic-led legislature nixed the film tax plan and instead eliminated a business tax break. That didn’t sit well with the business community, which supports Baker. A compromise delayed the business tax break and increased the EITC from 15 to 23 percent.

“We proposed one way of doing it, the Senate proposed another way, and we ended up with a third way,” Baker said.

In California, Brown signed a $115.4 billion budget that includes a new state EITC for working families—to be eligible, families with no dependents must earn less than $6,580 and families with three or more dependents must earn less than $13,870. Brown said the credit is expected to benefit 2 million Californians, with an average benefit of $460 per household.

“Given the tremendous growth in income on the part of higher-income people, I thought it would be reasonable to establish this program in California,” he said. The program is expected to cost $380 million in the first year.

In New Jersey, Republican Gov. Chris Christie and the legislature agreed to raise the state EITC from 20 to 30 percent of the federal credit. In 2010, the state’s EITC was reduced from 25 to 20 percent, to help close a budget deficit. But now, Christie said, it’s time to go in the other direction. Democrats in the legislature support the change.

“This is something that those families need now more than ever,” Christie said.

Maine’s final budget converted a non-refundable credit into a refundable one, bringing the state in line with the other 22 states where the tax is refundable. Only three states—Ohio, Virginia and Delaware—have non-refundable credits, meaning low-income workers can get back only as much as they paid.

Still Pending

In Michigan, retention of the state’s EITC is caught up in a fight over transportation funding. The House in June voted to eliminate the credit as part of a $1.2 billion road building bill. But the Senate’s transportation bill did not touch the EITC. The two chambers cannot agree on how to fund roads, leaving the EITC in limbo. The legislature will likely take up the issue again when it returns from summer recess.

In 2011, Michigan cut its EITC from 20 to 6 percent of the federal credit. In May, a referendum to fund road building, which would have restored the EITC to its earlier level, failed, pushing the issue to the legislature.

Karen Holcomb-Merrill, vice president of the Michigan League for Public Policy, which has mounted a Save EITC campaign, said the current state credit helps nearly 800,000 low-income Michigan families.

“It’s a lump sum of money that comes after you file income taxes for the year,” she said. “That can be significant for a family that might get several hundred dollars.” The average amount per family is about $143, she said.

In Illinois, where the state EITC is currently 10 percent of the federal credit, Democrats in the legislature approved a budget which would double that, to 20 percent. But there’s a standoff between Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and Democratic House Speaker Michael Madigan over the budget and the EITC seems to have been lost among larger disputes. The standoff is threatening to shut down parts of state government, though the legislature has been passing piecemeal legislation to try to keep critical public services going.

“It certainly is a mess,” said David Lloyd, director of the low-income advocacy organization Voices for Illinois Children. “We’re very hopeful that once there’s a resolution on the budget the EITC also will be expanded as part of that.”

Elaine S. Povich writes for Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

NEXT STORY: Millennials: Living on the Edge of the Big City