Dedicated to the Mountains, Desperate for Jobs

A coal barge floats past Dayton, Kentucky.

Connecting state and local government leaders

It’s never been easy to make a living in central Appalachia’s narrow valleys. Without coal, it’s become a whole lot harder.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Sophie Quinton.

PIKEVILLE, Ky. — The small green sign outside the employment center in this eastern Kentucky town said “JOB FAIR” and “TODAY!!” Inside, people hunched over applications for coal mining jobs in the western part of the state, and in Illinois and Indiana.

Cy Robinette and his son, Derrick, came out into the humid air. They had both been miners since high school — 29 years for Cy, 47, and eight years for Derrick, 27. Now the coal industry had collapsed, and they were getting out.

“There’s nothing here no more,” Cy said, leaning against a railing. The corners of his eyes creased beneath his baseball cap. He and his son didn’t have their hearts set on mining; they were hoping to land jobs at the Johnson Controls manufacturing plant near Cincinnati.

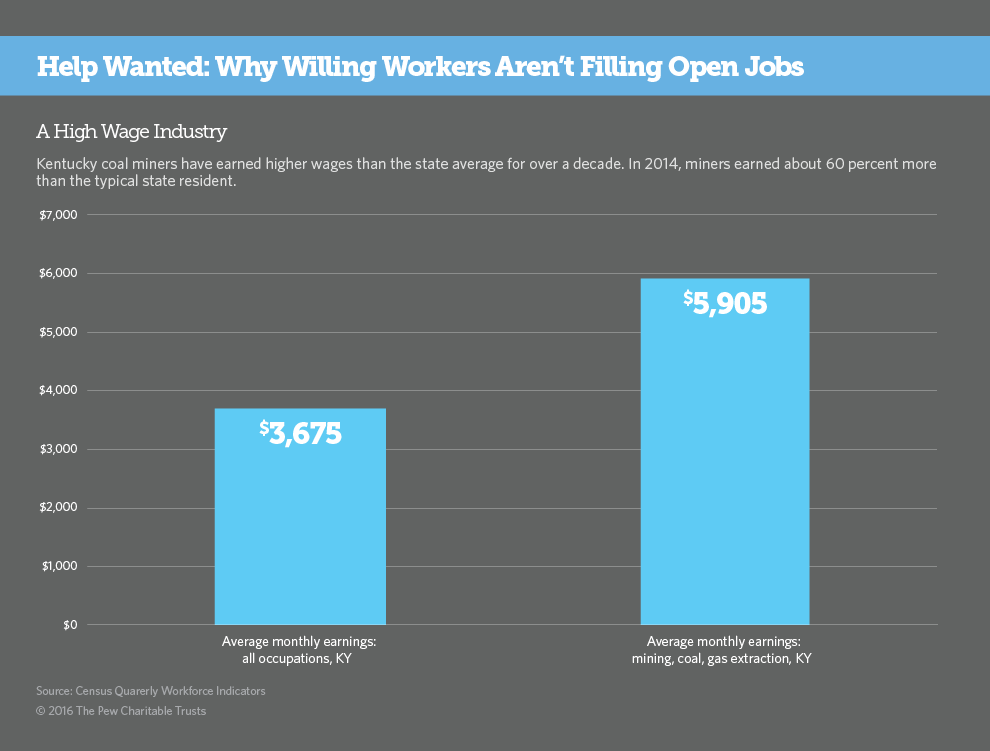

It’s never been easy to make a living in central Appalachia’s narrow valleys. Without coal, it’s become a whole lot harder. Mining jobs were some of the best-paying in the area, and the industry supported an array of other professions, from truck drivers to personal injury lawyers.

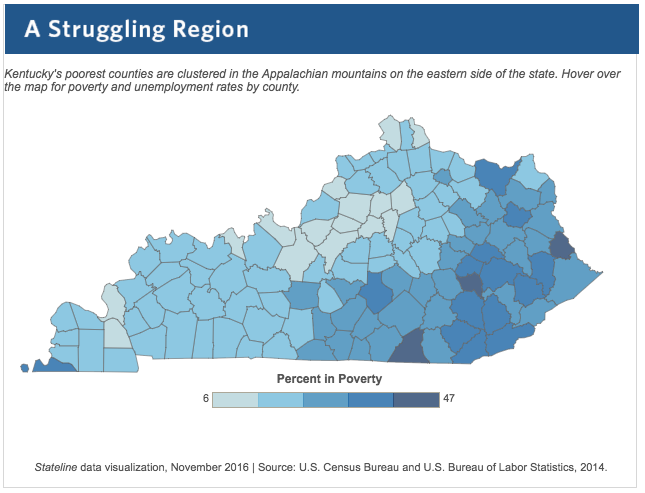

Today about 9 percent of eastern Kentuckians are out of work. Thirty percent live in poverty, according to the most recent federal statistics. Rates of drug overdose deaths, cancer, diabetes and disability are high.

President-elect Donald Trump has promised to rejuvenate the coal industry by renegotiating trade deals and rolling back environmental regulations. That might bring back some jobs, but it won’t bring back the employment levels of the 1980s or ’90s.

Even U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Kentucky Republican and a leading advocate for the industry, said it’s “hard to tell” if reducing regulation will bring back coal jobs.

So eastern Kentuckians are left weighing their options. Some laid-off workers are leaving and others are retraining for jobs in fields such as electrical work and nursing. But reinvention isn’t for everyone. Some locals are too old, sick or poor to restart their lives somewhere else. And retraining isn’t a surefire way to get a new job in a place where so few employers are hiring.

Local leaders have been doing everything they can to increase jobs in industries such as health care and retail and to attract new industries that pay well. Trump’s election won’t stop those efforts, said Pikeville City Manager Donovan Blackburn.

Devin Stephenson, president of Big Sandy Community and Technical College, a technical college with a campus in Pikeville, knows the region is racing against time.

“There is no question—no question—that we only get one shot at transforming this economy right now. We have one shot,” Stephenson said.

Stay or Go?

The economic situation in eastern Kentucky is so dire that this spring National Review magazine cited the region in an article that accused white, working-class people of lacking the gumption to leave distressed places. “They need real opportunity, which means that they need real change, which means that they need U-Haul,” author Kevin Williamson wrote.

It turns out that a lot of people are packing up. “People are leaving their homes. They’re not renting them, they’re not selling them, they’re just leaving them,” Blackburn said. Families keep calling the local utility company and asking it to turn off their power, he said.

But that doesn’t mean they’re moving far. Most of the people who packed up their homes in one of the roughly 30 counties in eastern Kentucky between 2011 and 2014 moved within the region, according to an analysis by Matt Klesta at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

“People are staying because they’re either dedicated to the mountains, the place, and their family, or they’re kind of trapped,” said Mil Duncan, a sociologist who has studied Appalachia.

Williamson’s bitter prescription makes the most sense for young people and those with skills and financial resources.

Gary Bentley, 33, is one such person. In 2013, he leveraged his skills as a supervisor at a mine to get a job outside the coal industry. He now works at a manufacturing plant near Lexington, and writes about his mining past for the Daily Yonder.

“Then you’ve got people like my father, who just lost his job a few weeks ago,” Bentley said when we spoke this summer. Bentley’s father is almost 60 and close to paying off his house. He feels tied to his property, yet stuck in a place where few jobs pay above the minimum wage.

“There’s a lot of people like that, you know, who have worked in the mine for 20-plus years,” Bentley said. “And they feel like leaving is worse than staying.”

It’s not just laid-off miners who feel stuck. Rachelle Wilson, 45, came out of the employment center a few minutes after the Robinettes, her strawberry blonde hair held back by a headband. She had lost her job as an insurance agent and was trying to get a new one as a medical receptionist, a position she had held before.

“If you’re not working at the hospital or the college, good luck,” Wilson said.

She and her husband have talked about leaving, she said. But her husband has a good job. Their kids are in high school. Wilson’s elderly father lives in a nursing home nearby. “I can’t just up and leave,” she said.

Because the cost of living in Appalachia is low, it’s possible to just give up the job search altogether. Some people can find a way to get by without working, typically with a mix of odd jobs, help from family, savings and government assistance.

Billy Church, 58, has no intention of leaving. I found him standing stiffly in the parking lot beside the employment center, smoking cigarettes and waiting for his son. “I was born here, I lived my life here, I intend to die here, as my forefathers have done before me. And my son feels the same way,” he said.

Church has already retired. Over his 25-year mining career, he said, he broke 15 bones and herniated 11 discs in his spine. Sitting for 20 minutes straight is excruciating. “Who would hire me?” he asked.

His wife suffers from a painful muscle disorder and also doesn’t work. Church was stretching the disability checks that he and his wife receive to also support their son and grandson.

Despite its economic struggles, there is a lot to love about eastern Kentucky. The kudzu-draped mountainsides press in cozily all around. Radio stations play bluegrass and country songs that praise the joys of small-town life. People like each other and feel out of place anywhere else.

Church did move away once, in the ’80s, to be a deputy sheriff in St. Clair County, Alabama. He found the area to be as economically depressed as the region he’d left. Plus, he and his wife were homesick. So they packed up their things and came back.

Rebuilding Hope

Stephenson, the community college president, gets riled up when he hears people say that there are no jobs left here.

When we met in his office he had just wrapped up a phone call with one of the lead administrators at the Pikeville Medical Center. “She called me and she said, ‘Help me. I have 200 openings right now for RNs [registered nurses]. Right now!’ ”

The health care sector is growing in eastern Kentucky, as it is nationally. Stephenson also said Big Sandy’s graduates in technical fields, such as welding and auto mechanics, all find jobs.

But retraining workers isn’t a complete solution to the local jobs crisis — overall, employers are laying off more people than they are hiring. Two hundred nursing jobs won’t replace thousands of lost mining jobs.

And getting job seekers to switch careers — let alone go back to college — isn’t easy. The career advisers at the Pikeville employment center see workers in every mood. “We have tissues on hand,” said Jenni Hampton, a career adviser. Many of the people who come in looking for help have never had to write a resume or prepare for a job interview before, she said.

For many laid-off workers, starting a new career that allows them to stay in eastern Kentucky has meant taking a painful pay cut.

Chris Crider, 31, went to barber college with help from a federal grant for retraining laid-off miners. His one-room barbershop, which he built with his dad and a family friend, sits off the road to the Prestonsburg Wal-Mart.

“I got lucky, because everybody’s going to Wal-Mart,” Crider said, kicking back in the room’s sole barber chair with a smile.

Reflecting on his new life, Crider is cheerful. But he knows his circumstances have changed. “I don’t even make a quarter of what I was making. I mean, I make a living, but it’s not comparable to what I was making,” he said. More recently, business has fallen as people have lost their jobs or moved away.

Many graduates of Big Sandy, which is named for a tributary of the Ohio River, have to leave the region to find work. That doesn’t bother Stephenson. “Until we get this economy up and ramped and working really like it needs to be — globally competitive — it may mean that you have to drive out for the job,” he said. But he tells his students, “The same road you drove out on will bring you right back.”

Big Sandy is training some people for jobs that don’t exist here yet, but local leaders are trying to encourage those industries to come to the region.

For instance, Kentucky plans to install fiber-optic cables statewide. The technical college has trained more than 100 former miners to connect the cables to people’s homes, although that work has barely started in the eastern part of the state.

The college also just welcomed the first 50 students into a computer coding program, operated in partnership with the White House’s Tech Hire initiative and a Lexington-based technology company. The hope is that such partnerships will help boost the nascent technology sector here.

Local leaders such as Blackburn also have been working to build up retail and tourism and to lure manufacturers and other blue-collar employers to the region with a mix of sweet talk and financial incentives.

Jobs are still so scarce in some places that the Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative, which provides supplies and other services to 19 school districts in the region, has had to come up with new ways to expose students to possible careers.

Paul Green, a member of the cooperative’s leadership team, said in the rural county where he grew up, the school district itself was the largest employer; the second largest was a nursing home.

So Green and his team help elementary, middle and high school students become entrepreneurs, encourage them to brainstorm solutions to local problems, and make sure schools offer classes in cutting-edge fields such as computer science and aviation. The idea is to nurture creative thinkers, young people who might create their own businesses or attract new industry to the region with their skills.

It’s not always easy to get teachers and principals on board, Green said, but students love these projects.

Locals are angry and “grieving” over the demise of the coal industry, said Ron Daley, who works on strategic partnerships for the cooperative. With so many people close to despair, he said, it gives everybody a lift when kids come home excited about the future.

This Story is Part Three of Help Wanted: Why Willing Workers Aren’t Filling Open Jobs.

NEXT STORY: Why the ‘Skills Gap’ Doesn’t Explain Slow Hiring