In Most States, a Spike in ‘Super Commuters’

Connecting state and local government leaders

Super long commutes of 90 minutes or more are growing fast in more states as rent hikes force service workers farther away from cities and some choose “hinterlands” for telecommuting.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts and was written by Tim Henderson.

The number of commuters who travel 90 minutes or more to get to work increased sharply between 2010 and 2015, a shift that traffic experts, real estate analysts and others attribute to skyrocketing housing costs and a reluctance to move, born of memories of the 2008 financial crisis.

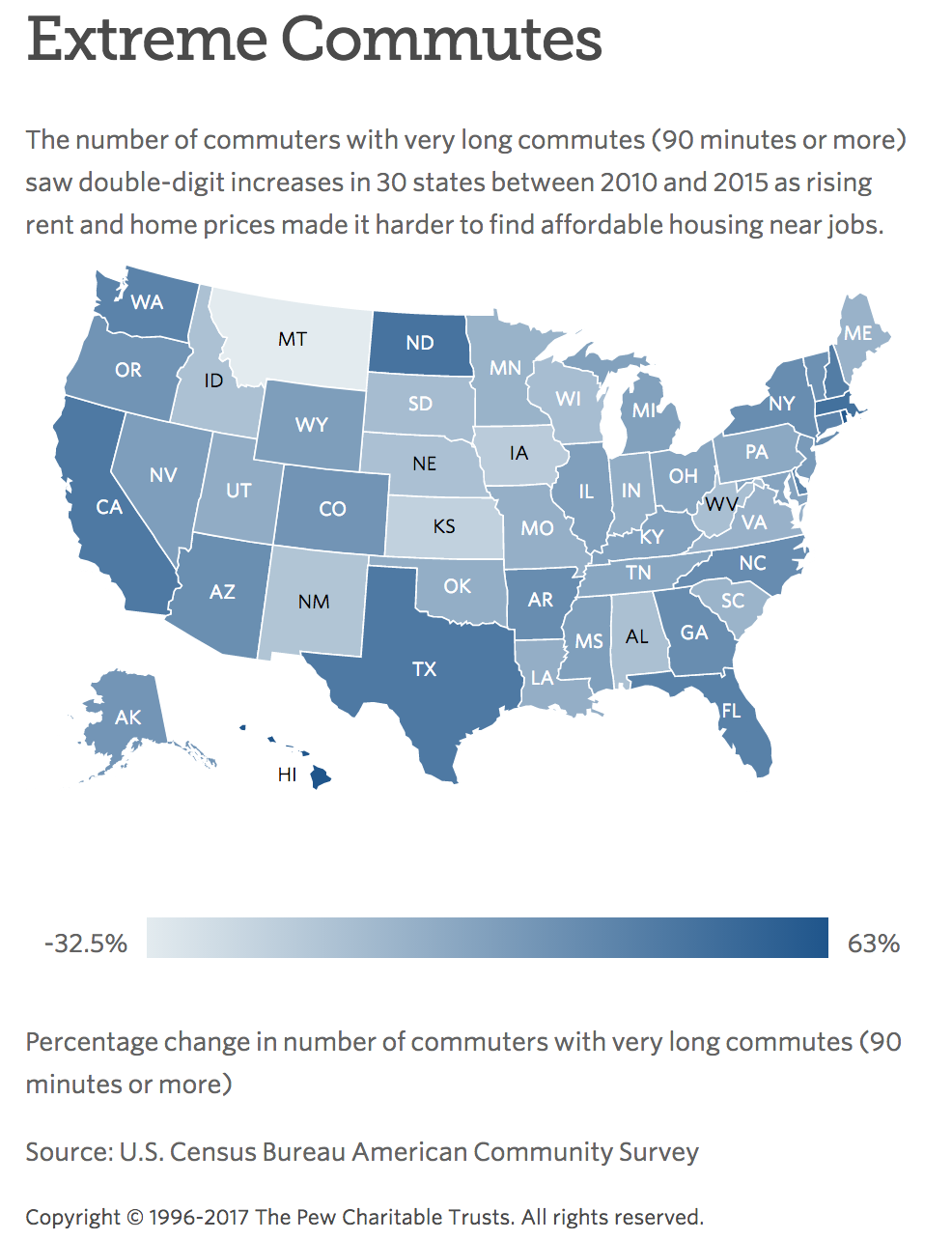

In all but 10 states, the number of “super commuters” increased over the period, and in California, Hawaii, Massachusetts, North Dakota and Rhode Island, it grew by more than 40 percent, according to census data. The growth came amid an overall increase in the number of commuters as the economy improved, but the increase in the number of people with the longest rides, 23 percent, was almost three times the increase in the number of those with shorter commutes, close to 8 percent.

People with 90-minute commutes still represent a small share of commuters — ranging from 1 percent in Nebraska to nearly 6 percent in New York. But analysts say the spike in long trips reflects several broader trends in the economy.

After years of sharp rent increases, service workers can’t compete for urban apartments near their jobs. Those who found new jobs after the recession may not feel secure enough yet to move closer to work, especially as prices soar near job centers.

The term “commuter” includes anybody who has a job and doesn’t work at home.

In tech job centers like Seattle and San Francisco, low-income workers are moving farther and farther away while high-income workers can still afford to live close to work, according to a 2015 Zillow study that looked at changes through 2014.

“While commute times for higher-income earners hasn’t changed much over the past 10 years, commutes are getting longer and longer for low-income workers,” said Lauren Braun, a Zillow spokeswoman.

Even among those who could afford to live anywhere, more are choosing faraway places because they can telecommute much of the time, said Mitchell Moss, an urban policy professor at New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management who has studied super commuters.

“The real change is that the suburbs have been eclipsed,” Moss said. “People are moving directly from the city to the hinterlands.”

The number of super commuters grew in a variety of jobs, from lawyers and computer scientists to teachers, cooks, janitors and maids, according to a Statelineanalysis of census data provided by ipums.org at the University of Minnesota.

Among elementary and middle school teachers, for instance, super commuters increased by 26 percent from 2010 to 2015. Police officers similarly saw a 31 percent increase in super commuters.

Oil and gas workers were the most likely to have super commutes, at 19 percent in 2015, while 18 percent of aircraft pilots and 16 percent of elevator repairmen faced rides of 90 minutes or more. On the other hand, fewer than 1 percent of telemarketers and funeral embalmers who commute to work faced rides of 90 minutes or more.

Workforce Housing and Rent Increases

With growing evidence that essential employees like teachers and police officers are having trouble living in the cities they serve, lawmakers in some states with fast-climbing rents have introduced bills this year to encourage more affordable worker housing. Massachusetts, for instance, is considering a bill that would allow Nantucket to charge a fee on home sales to help pay for affordable housing.

Massachusetts, along with New York, Washington state and California, where similar legislation to encourage more workforce housing is also pending, experienced higher than average median rent increases between 2010 and 2015, along with some of the biggest growth in super commutes.

For instance, Massachusetts saw median rent rise 15 percent in the five-year period, according to census data, while the number of super commuters rose 45 percent.

But even higher earners with new jobs in today’s recovering economy may be unwilling to move closer to jobs, especially in highly competitive housing markets where prices are rising quickly, Moss said.

“The long-term effect of the 2008 financial crisis is a reluctance to move because people don’t know if the economy is going to collapse again,” Moss said.

Hawaii’s Tourism Boom

In Hawaii, people in relatively low-paid tourism jobs have to travel long distances to get to tourist spots in Honolulu, where those jobs are concentrated, said Panos Prevedouros, a traffic engineering professor at the University of Hawaii.

Tourism was still down after the recession in 2010, he said, and has since come roaring back — drawing more workers to affordable areas west of the city and creating more traffic jams on the limited roads between them, making commute times even longer.

“Hotel pay is modest and these workers tend to live far from Waikiki [a beach neighborhood of Honolulu] and downtown Honolulu, in remote towns that come with 75-minute commutes or more,” Prevedouros said. During the recession, he said, lighter traffic meant fewer 90-minute trips, even from far-off locales. But now, “when the economy is booming, even close-in suburbs will experience occasional 90-plus-minute trips,” he said.

The number of Hawaii residents commuting 90 minutes or more increased 63 percent from 2010 to 2015, to almost 17,000.

Eugene Tian, Hawaii’s chief state economist, said the population in the affordable areas west of Honolulu grew 50 percent faster between 2010 and 2015 than the pricier areas around downtown Honolulu and Waikiki, which could help explain the increase in longer rides.

Decline in Some States

In the few states where the number of long commutes declined, generally low-cost states like Montana, Kansas and Iowa, some transportation experts say it might be due to a decline in the fracking boom that had drawn workers to cross state lines in search of lucrative oil and gas jobs in 2010.

In Iowa, the number of super commuters declined by 12 percent. But many state residents are still seeing longer trips to work as jobs become more concentrated in places like Des Moines. Compared to 1990, fewer people are commuting less than 20 minutes and more are commuting 20 to 45 minutes, according to a state report published this year.

In Montana, which had the biggest decrease in super commuters, falling by almost a third to 7,155, one explanation may be the slowdown in energy hiring that came when oil prices started to fall in 2015, said David Kack, a program manager for the Western Transportation Institute at Montana State University.

Oil fields in North Dakota near the Montana border, which were still ramping up in 2010, drew some local workers who may have since come back or moved closer, Kack said.

“When housing was tight, people were staying in Montana and commuting to North Dakota,” Kack said.

NEXT STORY: Should the Government Guarantee Everyone a Job?