L.A.’s Teachers Got What They Wanted—For Their Students

Shutterstock

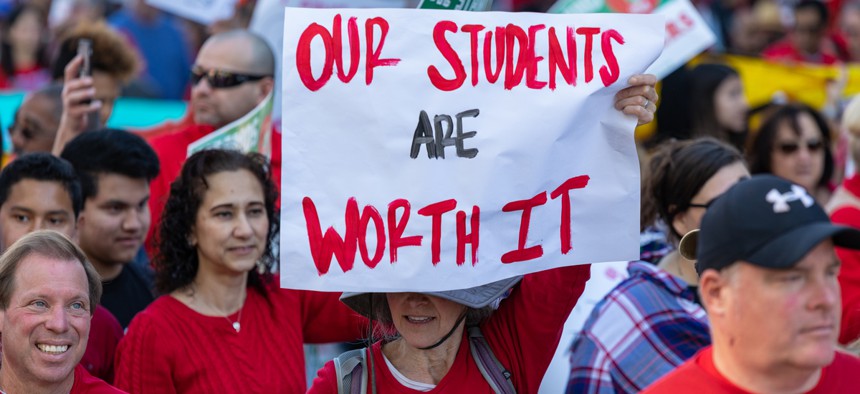

The strike showcased unions' strategy of advocating not just for their members but also for better resources for schools.

Teachers across Los Angeles fought hard and, after just over a week of striking, got more or less what they had hoped for: more librarians and nurses for their schools, smaller class sizes, and nicer campuses. Not on that list? Higher pay—the teachers had already successfully negotiated a 6 percent raise before the strike.

This is the most significant part of the L.A. teachers’ strike story, and the key to understanding the broader dynamics of today’s teachers’ movement. Salaries were never a major sticking point in the negotiations: The final figure for the raise is 6 percent, identical to the numbers that the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) had outlined in its most recent set of offers—and, in fact, pretty much the same as the number negotiated even before the strike began.

“Our salary demands have pretty much been met, so we’re clearly not striking for that issue per se,” Martha Infante Thorpe, a veteran social-studies teacher and Eastside L.A. native, told me on the eve of the walkout. Instead, she—like the handful of other educators I interviewed—stressed that she and her fellow LAUSD teachers were striking as a last-ditch effort to improve the education of the nearly 500,000 children they serve.

Topping the union’s list of priorities were demands around class sizes, which in many schools often exceeded the limits stipulated in the teachers’ previous contract—and in some cases were well upwards of 40 kids. While research on the benefits of class-size reduction is mixed, a number of compelling studiessuggest that smaller class sizes can be a significant predictor of student success. Another concern: the paucity of school staff tasked with supporting students’ extracurricular needs and well-being. Many campuses, for example, have for years operated without a full-time librarian or nurse, and a 2017 report foundthat a Los Angeles public-high-school counselor’s average caseload was 378 students, though that might have been a conservative estimate given recent analyses of the settlement, which concluded that the small number of additional hires will leave the ratio at 1 to 500. Nationally, the recommendedstudent-to-counselor ratio is 250 to 1. Yet the ratio should, arguably, be even lower than that in the Los Angeles public schools, which suffer from one of the greatest concentrations of student poverty among California’s school districts, with more than eight in 10 students relying on subsidized meals.

On both of these issues the teachers basically got what they wanted: class sizes will go down—immediate reductions for secondary math and English classes (from a limit of 46 students to 39) and, eventually, modest cuts to the size caps for every class in all but the earliest grade levels—and the number of support staff will go up, including hundreds of new nurses and dozens of new librarians. And it was on these issues that the differences between LAUSD’s earlier offers and the final compromises are most striking. Pronounced juxtapositions tend to signal areas that were the biggest sources of dispute in the negotiations, revealing what most preoccupied teachers.

In general, the agreement requires that the district, over the course of several school years, invest $403 million in those staffing increases and class-size reductions—more than three times the amount the district had offered in its final contract proposal before the strikes. Beyond those funding commitments, the union is claiming victories in its promotion of “community schools” designed to improve the well-being of both the students and their broader social networks, as well as in its condemnation of random searches of students on certain campuses. It even secured the district’s vow to add more green space to school campuses (by removing asphalt, for example, or creating more verdant play areas), though the details have yet to be hashed out.

While the strike’s outcomes are largely school- and student-focused, educators, too, will benefit, notes Mark Hlavacik, a communications professor at the University of North Texas who studies teachers’ union rhetoric. They’ll have smaller classes to manage, more help from other school staff, and fewer headaches over standardized testing, which, as part of the contract, the school district has agreed to curtail. But the important takeaway is that teachers are advancing themselves as advocates for students and and schools.

“What is impressive here is how well the teachers are folding their interests and the interests of their students together to create an outcome that any parent would be pleased with for the sake of their child in the district,” Hlavacik told me in an email. This pattern is not going to be limited to Los Angeles. In Denver and Oakland and Virginia, teachers are saying their professional demands are synonymous with kids’—and society’s—general well-being, a sign that this is an approach that future educator walkouts are bound to leverage.

Alia Wong writes for The Atlantic, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: Where Public Sector Union Membership Is Shrinking and Growing