Pay Transparency Laws Raise Women’s Salaries (and Slightly Lower Men’s)

Getty Images/Sorbetto

Multistate companies are finding ways to circumvent the laws.

This article originally appeared on Stateline.

The bestselling 2016 book “Hidden Figures,” later adapted into a popular film, told the story of Black female mathematicians who played an essential role in the U.S. space program in the 1950s and 1960s, but who faced racial discrimination and were paid less than their male counterparts.

The gender pay gap existed before the era portrayed in the book and film, and it persists today, though it has narrowed in recent years. In 2019, the national median salary for women working full time was $43,394, compared with $53,544 for men, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The sponsor of a West Virginia bill that aimed to close that gap there named it for two of the mathematicians featured in the book and film, Katherine Johnson and Dorothy Vaughan, both of whom were born in the state. The bill, which has been introduced for several sessions but has failed to pass, would require employers to publish salaries when advertising jobs and would prohibit companies from retaliating against workers who discuss their pay with colleagues.

Studies show that salary transparency—coupled with laws prohibiting companies from asking an applicant about their current or previous pay—can narrow the gender pay gap. If companies must advertise salaries for open positions, and current employees can freely discuss pay, applicants are less likely to receive or accept lowball offers. Studies show that women and minority candidates are most likely to receive such offers.

But research also shows that salary transparency tends to lower men’s salaries even as it raises those of women—and might lower salaries overall. Multistate companies have found ways to circumvent the laws by refusing to accept applications from job seekers who live in states that require transparency. And critics say salary transparency laws might persuade companies to hire fewer employees, and could foment conflict in the workplace.

State Rep. Barbara Evans Fleischauer, the Democratic sponsor of the West Virginia bill, said it has foundered against opposition from Republicans and business interests. “One member said: ‘I don’t want my secretary talking to others about what they make,’” she recalled.

But 17 states already have similar pay transparency laws. In March, Washington Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee signed legislation requiring employers with 15 or more workers to post salary ranges beginning in 2023. A similar Rhode Island law is scheduled to take effect next year.

There are no readily available studies on whether state transparency laws have helped close the pay gap, since the first of the laws took effect just a few years ago, in 2018.

But a 2019 study of Canadian universities, which have similar requirements, found the laws “reduced the gender pay gap between men and women by approximately 20-40 percent.”

“It’s very hard to lowball some new potential employee if the new potential employee is capable of looking at a range of salaries,” said Cornell economics assistant professor Thomas Jungbauer. “This can have a positive effect on wage gaps because of gender or color. Employers might offer lower wages to certain types of applicants. This makes it harder.”

Seventeen states have pay transparency laws, which require job advertisements to list starting salary ranges. Other states are considering similar laws. Advocates say in addition to being informative for job applicants, the laws help ease gender pay inequity.

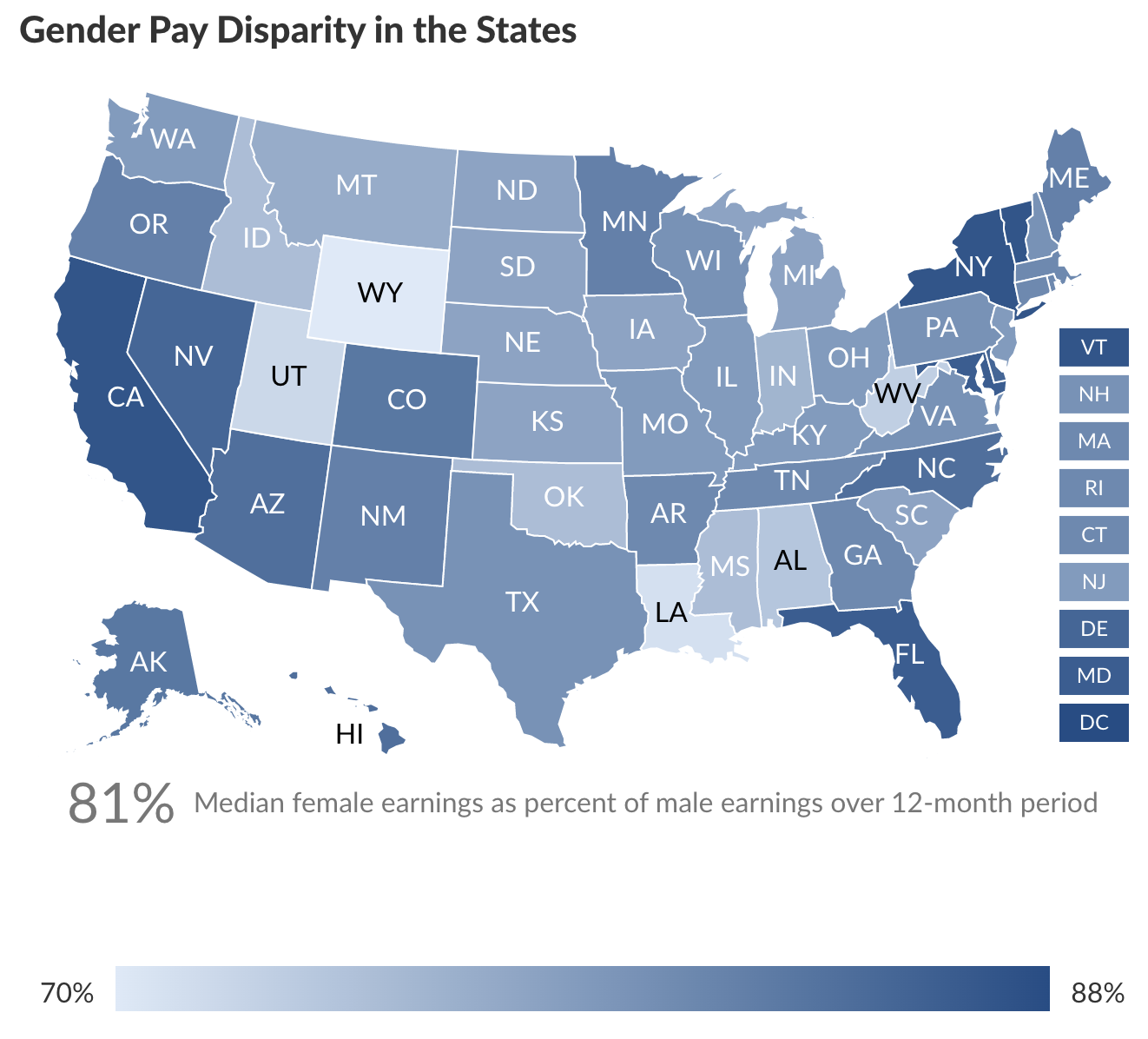

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, median earnings for women in the 2016-2020 period, the most recent period for which samples were taken, showed women making 81% of what men earn as a median salary. That’s better than the 59 cents on the dollar earned by women during the “Hidden Figures” era, but still well short of equal.

The 2019 census data also shows that the gender pay gap varies significantly from state to state. The District of Columbia, Utah and Wyoming all had gaps that exceeded $15,000, while the gap was less than $10,000 in states including Arizona, California, Florida, New York and North Carolina.

New York Debate

New York City’s pay transparency law was scheduled to take effect this month, but the City Council in April voted to postpone implementation until November because of business concerns about a lack of flexibility and worries that the law had been approved too quickly, according to Beverly Neufeld, president and founder of PowHer NY, a network of gender and racial justice organizations.

The new law will require that employers get a warning and 30 days to fix their first violation before facing fines. It also eliminated the right to sue an employer for not posting salary ranges unless you are employed there.

The Staten Island Chamber of Commerce was one organization that argued against the law, saying that it would disadvantage New York companies. Forcing them to publicize salaries for open jobs, the chamber argued, would push prospective employees to look elsewhere for higher compensation.

“The city’s [minority- and women-owned business] firms are generally at a disadvantage in competing for scarce talent and are likely to be outbid if a majority competitor has access to their salary offering,” the chamber said in a statement.

New York state is considering a similar bill. State Rep. Latoya Joyner, a Democrat and primary sponsor of the bill, said in an email to Stateline that while the state has taken a significant step toward closing the salary gap by prohibiting companies from asking interviewees about their salary history, it will go even further with this legislation.

Overall, the pay gap between men and women in New York state in 2019 was $8,821, with women making 85.5% of what men make, but that gap differed by race and ethnicity. For White workers the gap was $12,000 (83%), while it was $3,500 for Hispanic workers (92%) and $2,900 for Black workers (94%). There was no gender pay gap for Asian workers.

“Workers—especially women—still face a very daunting work environment when it comes to compensation, and we need to do more to create a level playing field in the workplace when it comes to salaries,” Joyner said.

The bill is awaiting action in both the Senate and the Assembly, and Joyner said she was hopeful it would pass in June.

Limited Effectiveness?

Colorado’s transparency law went into effect last year, but an investigation by television station 9News in Denver found at least 10 companies in May 2021―including Nike, Johnson & Johnson and Lincoln Financial―saying in their ads that no Coloradans need apply for their openings. A subsequent Colorado Department of Labor ruling underscored the regulation and said that no company is exempt, even if the jobs are for remote work.

Meanwhile, a study in 2021 by Harvard Business School assistant professor Zoe Cullen showed that making pay scales public reduces “the individual bargaining power of workers, leading to lower average wages.” The study found the wages went down by 2%, mostly by lowering men’s pay. The study used salary data from the American Community Survey and compared overall salaries in states where pay transparency exists to those where it doesn’t. It modeled future effects based on those statistics.

“Both the empirical work and that model showed that when employers catch wind of the fact that there’s greater transparency and have time to adjust pay setting practices, they do so by bargaining more aggressively,” she said in a phone interview. “They know that by raising your wage, it weakens their negotiations. The upshot is that average wages are overall lower.”