To Get Off Fossil Fuels, America Is Going to Need a Lot More Electricians

Electricians hook up solar panels on roof of high school in San Francisco. Lea Suzuki/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

Connecting state and local government leaders

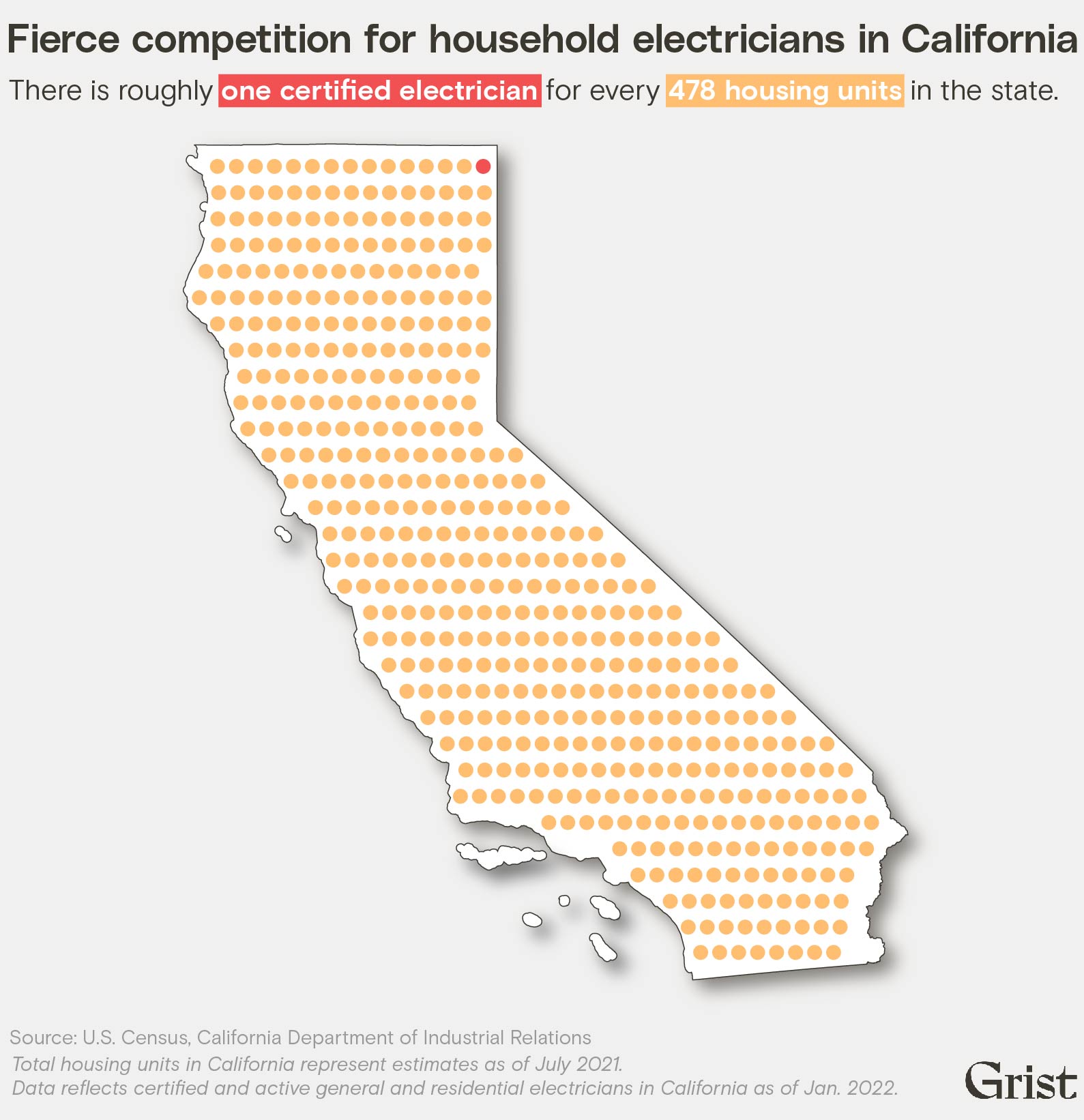

A shortage of skilled labor could derail efforts to "electrify everything."

Chanpory Rith, a 42-year-old product designer at the software company Airtable, bought a house in Berkeley, California, with his partner at the end of 2020. The couple wasn’t planning to buy, but when COVID-19 hit and they both began working from their one-bedroom San Francisco apartment, they developed a new hobby: browsing listings on Zillow and Redfin—“real estate porn,” as Rith put it.

Their pandemic fantasizing soon became a pandemic fairy tale: They fell for a five-bedroom, midcentury home in the Berkeley hills with views of San Francisco Bay and put down an offer. “And then came the joys and tribulations of homeownership,” Rith said.

One of those tribulations began with a plan to install solar panels. Rith didn’t consider himself a diehard environmentalist, but he was concerned about climate change and wanted to do his part to help. He didn’t have a car but planned on eventually getting an electric vehicle and also wanted to swap out the house’s natural gas appliances for electric versions. Getting solar panels would be a smart first step, he figured, because it might trim his utility bills. But Rith soon found out that the house’s aging electrical panel would need to be upgraded to support rooftop solar. And he had no idea how hard it would be to find someone to do it.

Many of the electricians Rith reached out to didn’t respond. Those who did were booked out for weeks, if not months. He said they were so busy that the conversations felt like interviews—as if he were being evaluated, to suss out whether his house was worth their time.

“It felt like trying to get your kid into a nice kindergarten, where you have to be interviewed and do a lot of things just to get on the radar of these electricians,” Rith told Grist.

His first-choice contracting company put him on a long waitlist before it would send anyone out to look at the house. Another gave him an exorbitant quote—more than $50,000 to upgrade the electrical panel, along with installing new, grounded outlets to replace the house’s outdated two-prong outlets. Rith wound up putting the project on hold to do some renovations first.

Andrew Campbell, executive director of the University of California, Berkeley’s Energy Institute, had a similar experience. Campbell wanted to upgrade the electrical panel on a duplex he owns in Oakland so that he could install electric vehicle chargers for the building’s tenants. But even after finding a company to take the job, a shortage of technicians and the contractor’s overbooked schedule, among other delays, meant it took eight months from the time the first electrician came over until the project was done.

“I was feeling like, why am I doing this?” Campbell said. “The electricians who should want the project don’t seem to want it. The utility, which is really going to benefit a lot from electrification, they’re making it hard. It just felt like barrier after barrier.”

You could read Rith and Campbell’s troubles as minor inconveniences, or you could read them as warning signs.

To cut greenhouse gas emissions on pace with the best available science, the United States must prepare for a monumental increase in electricity use. Burning fossil fuels to heat homes and get around isn’t compatible with keeping the planet at a livable temperature. Appliances that can be powered by clean electricity already exist to meet all of these needs.

The race to “electrify everything” is picking up. President Joe Biden’s signature climate legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, signed in August, contains billions of dollars to help Americans electrify their homes, buy electric vehicles, and install solar panels. Meanwhile, cities all over the country, including New York, Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco are requiring that new buildings run only on electricity, after the city of Berkeley, California, pioneered the legislation in 2019.

The problem is, most houses aren’t wired to handle the load from electric heating, cooking, and clothes dryers, along with solar panels and vehicle chargers. Rewiring America, a nonprofit that conducts research and advocacy on electrification, estimates that some 60 to 70 percent of single-family homes will need to upgrade to bigger or more modern electrical panels to accommodate a fully electrified house.

“It’s going to be the electrification worker, the electricians that are going to see a real surge in demand,” said Panama Bartholomy, executive director of the Building Decarbonization Coalition, a national nonprofit working to get fossil fuels out of homes.

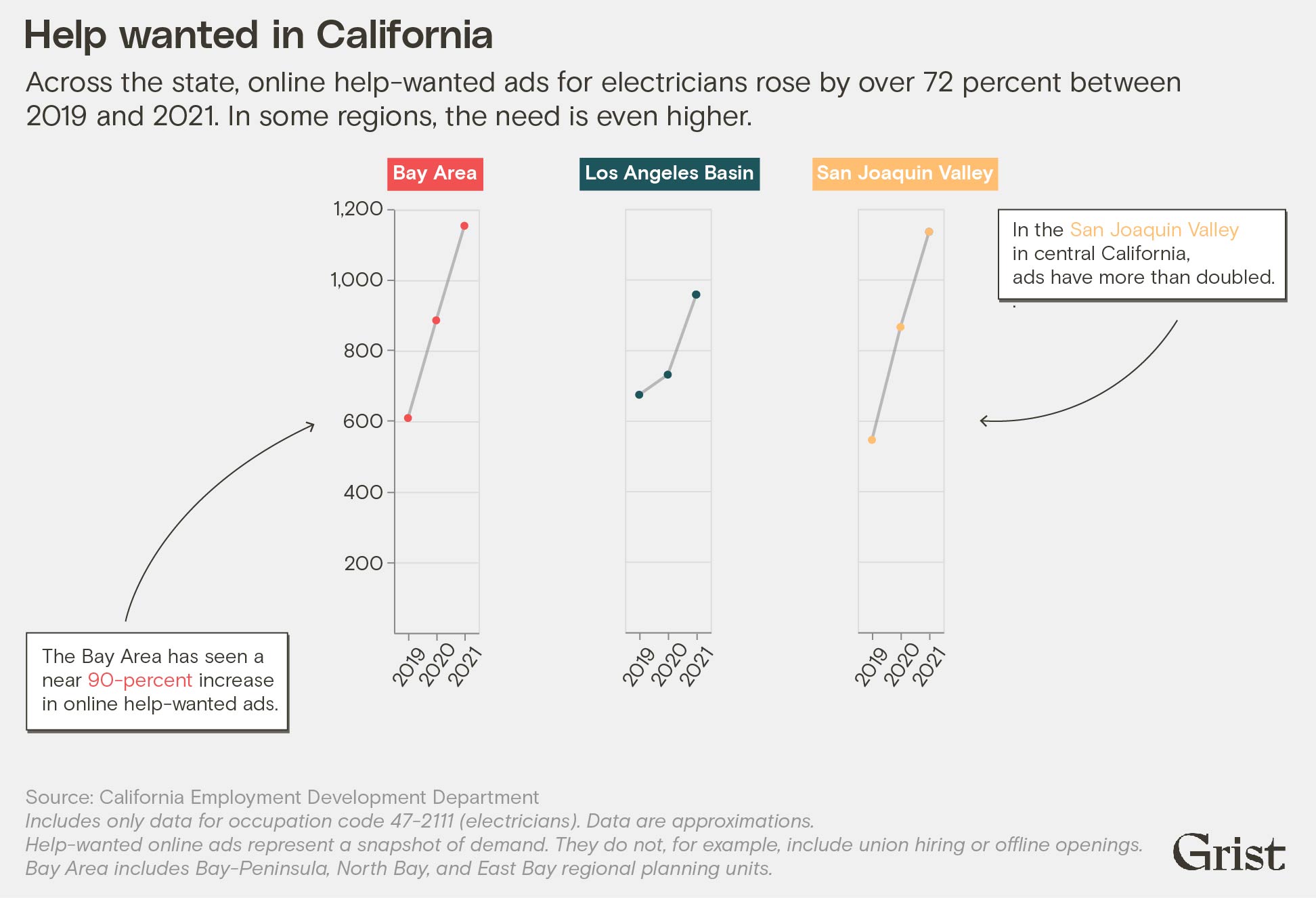

But in the Bay Area, arguably the birthplace of the movement to “electrify everything,” homeowners are struggling to find technicians to upgrade their electrical panels or install electric heat pumps, let alone for everyday repairs. Residential electrical contractors are swamped with calls and struggling to find experienced people to hire. The schools tasked with training the next generation of electricians are tight on funds and short on teachers. It’s a story that’s playing out across the country. And what might be inconvenient today could soon hamstring attempts to cut carbon emissions even as these efforts become more urgent.

“It is hard to imagine tens of millions of households in the U.S. individually undertaking the sort of time consuming, expensive process that I experienced,” wrote Andrew Campbell in a blog post chronicling his experience.

The contractor Campbell ended up working with was Boyes Electric, a small company based in Oakland owned by Borin Reyes.

Reyes, who’s 28, moved to California from Guatemala when he was 16 and got introduced to electrical work in high school. His dad was a general contractor and would take him out in the field during summer break. On one job, there was an electrical subcontractor who needed an extra set of hands, and Borin started working for him from time to time. He liked the work — but more so he liked the money he was making. After graduating from high school, he saw electrical work as a path to moving out of his parents’ house, so he enrolled in a training program at a now-shuttered for-profit technical school in Oakland to get more experience.

After graduating in 2013, Reyes spent several years working for a larger company before starting his own. Today, he loves the job. “You really have to be focused, because of safety,” he said. “You have to be hands-on most of the time and solving problems. That’s one of the things that I like best—solving problems.”

Reyes’ company has always focused on rewiring homes undergoing renovations rather than new construction. But at the beginning of 2022, he added a new specialty when his business partnered with a company called QMerit, a middleman between electric vehicle dealerships and electricians. Dealerships send new car owners to QMerit to get help finding qualified technicians to install EV chargers, and QMerit connects them with local businesses like Boyes Electric.

Electric vehicles make up less than 1 percent of cars on the road, but that’s changing fast as sales soar. The number of electric vehicles registered in the U.S. jumped nearly 43 percent between 2020 and 2021, according to the Department of Energy. Government incentives are sure to give the market another boost: The Inflation Reduction Act offers as much as $7,500 in rebates for new EVs and $4,000 for used EVs. In California, Washington state, and New York, you won’t even be able to buy a new model with an internal combustion engine after 2035. The number of public charging stations is also growing, so EV owners don’t necessarily need to install their own charging equipment at home, though many do. It’s convenient, and can also turn a car into a backup power source when the lights go out.

Before Boyes Electric partnered with QMerit, Reyes was installing around one EV charger every week; now it’s up to about five each week. “That’s huge for a small business,” he said. Reyes wants the company to expand into solar installations, too—just not yet.

Boyes Electric employs 12 technicians, and these days Reyes spends most of his time in the office taking calls and coordinating jobs. His electricians are usually booked up about three weeks to a month out.

“Customers are literally looking for electricians every single day,” he said. “We’re not taking emergency calls anymore because we don’t have the manpower. All of our current technicians are out on the field, they’re busy trying to get jobs done.”

Reyes would like to hire more electricians, but he said there just aren’t any experienced people looking for work; they’re already hired. “It is a problem finding people right now,” he said. “Most of the electrical companies, you can ask around, all of them are busy.”

In 2021, the website Angi, which helps homeowners find services, surveyed 2,400 contractors across different trades. Half reported that they couldn’t fill open positions, and 68 percent said it was a struggle to hire skilled workers. In a recent survey of 661 building contractors by the Associated General Contractors of America, 72 percent reported having open, salaried positions. The number one reason for all the openings: “Available candidates are not qualified to work in the industry.”

In the past, Reyes recruited workers out of high school and trained them up. But he’s reluctant to do it again. It costs his technicians time, it costs him money, and there’s no guarantee that the people he invests in will stick around because the job market is so competitive.

The workforce is also aging. Reyes said he knows of a few electricians getting ready for retirement who would like to hand over the business to their kids, but they just aren’t interested. The way he sees it, younger people are getting lured into the tech industry with the promise of big salaries and just aren’t as interested in getting dirty underneath houses.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that about 21 percent of electricians will have hit retirement age in the next 10 years. The agency estimates that demand for electricians will grow by 7 percent over the same span and that between retirements and new demand, there will be nearly 80,000 job openings in the field every year. That estimate doesn’t account for all the incentives—rebates for solar panels, electrical panels, heat pumps, stoves, cars, and clothes dryers—contained in the Inflation Reduction Act, nor does it account for the possibility that demand might soar if local governments keep pushing to electrify buildings.

Several contractors and labor experts, when asked why electricians are so hard to find, pointed to the widespread belief that the main path to adulthood runs through a four-year university, and the related decline of vocational education in high schools. According to Pew Research, 39 percent of millennials earned a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 29 percent of Gen Xers and 24 to 25 percent of boomers.

Even for those drawn to a career in the trades, there’s another obstacle: The technical schools built to train them are short of money and people, too.

In the Bay Area, one of the main ways that aspiring electricians can get into the field is by taking classes at Laney College, a community college in Oakland. The school’s electrical technology program is approved by the State of California’s Industrial Relations Board, meaning students at Laney can count their hours toward the requirements to take the state certification exam. More than 380 students have earned an associate degree or certificate in the program over the past five years.

But this past year, Laney’s program almost fell apart after one of its teachers, Forough Hashemi, announced she would be retiring at the end of the spring 2022 semester. Hashemi had been teaching six classes each semester, essentially holding the program together, and to some students, it felt like the fate of the entire program was in question.

David Pitt, a student at Laney, was worried he wouldn’t be able to finish the required courses. Pitt got interested in becoming an electrician a few years ago while volunteering for a solar company. He enjoyed being outside, working with his hands, and getting away from his computer screen. The volunteering gig soon turned into a paid, part-time job, but all he was really allowed to do was grunt work, like mounting solar panels and running wires. In order to do the interesting stuff—design a system, interpret an electrical panel, actually connect the solar panels to it, and maybe work his way up to owning his own business—he needed to become a certified electrician. So he enrolled part-time in Laney’s electrical program.

Without Hashemi, however, it was unclear whether the school could keep offering the required classes. So Pitt and his classmates, assisted by an adjunct professor, Mark Prudowsky, arranged a meeting with the school’s deans to ask what would happen next. The deans assured them that they would try to replace Hashemi, though they admitted they were having trouble finding anyone interested.

“This is an issue for a lot of trade skills disciplines,” said Alejandria Tomas, the career and technical education dean at Laney, in an interview last summer. By that point, Tomas had already tried emailing every electrical business in the county and felt she had exhausted every resource she had in trying to recruit a new teacher. (Borin Reyes was one of those who turned her down.)

“Employees usually earn more when they work in the field than teaching, so it’s hard to recruit,” Tomas said.

Pitt only needed two more classes to finish his required coursework—one on motors and another on lightbulbs. But by the time the fall semester started, Laney had yet to make any full-time hires, and the lightbulbs class wasn’t offered.

Prudowsky blamed the school, the district, and the state for not investing enough in Laney’s electrician program. The lack of funds meant requiring one full-time faculty member to teach up to six classes per semester with up to 40 students in every class. (Hashemi did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.)

“If California is even going to come close to meeting its very ambitious goals, it’s going to have to train a whole cohort of electricians and technicians,” Prudowsky said. “And if they keep underfunding these programs and overloading these classrooms and not providing enough resources, it won’t happen.”

Tomas, the dean, said the school understands the importance of the program and has shielded it from recent budget cuts. The problem, as she saw it, was that it was simply impossible to find more people to teach the courses.

In January, nearly a year after the search began, the school finally hired a new full-time faculty member. According to Prudowsky, however, the big problem—“a very poor understanding of the need to fund and indeed, expand funding for the program”—remained.

Community colleges like Laney are one of a handful of pathways into the profession. Another runs through the unions, which offer free classes and paid experience through their apprenticeship programs. There’s often a higher barrier to entry than simply signing up for classes: In the Bay Area, for instance, an aspiring electrician has to pass an exam and go through an interview process to get accepted. And there are limited openings.

Labor advocates like Beli Acharya, the executive director of the Construction Trades Workforce Initiative, make the case that California should enact policies that favor union contractors, which would increase demand for apprentices and enable the unions to accept more applicants. Today, according to Acharya, most residential building work is handled by nonunion contractors, though that’s not because union contractors aren’t interested in working on houses. She said they are undercut by cheaper, nonunion companies.

Acharya’s organization is a nonprofit partner to several building trades unions in the East Bay. It aims to help people who are currently underrepresented in the trades gain access to these careers. Nearly 90 percent of electricians are white, compared with 78 percent of the country’s workforce, and less than 2 percent are women, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Our goal is to ensure that as public dollars become available, quality jobs are being produced,” Acharya said. “If we’re really trying to lift up our communities and create quality jobs, there needs to be labor standards put in place so that our community members are actually benefiting from the work that’s going to be developed through all of this construction.”

The Construction Trades Workforce Initiative is one of several organizations in the Bay Area trying to entice more people into jobs connected to clean energy, like electrical work. Another nonprofit headquartered in Oakland, GRID Alternatives, builds solar projects and trains people to install them. GRID partners with local organizations, like Homeboy Industries, a gang intervention program, to introduce former inmates as well as other underrepresented people, to careers in solar. Those admitted to GRID’s training receive “wraparound supportive services” that address barriers they might have to participating, like helping them get driver’s licenses, open bank accounts, or, for those formerly incarcerated, find attorneys.

GRID’s program isn’t specifically geared toward producing electricians. But Adewale OgunBadejo, its workforce development manager, said that it can act as a gateway into the skilled trades—similar to how David Pitt was inspired to become an electrician after volunteering for a solar company. “It’s really an introduction into the industry,” he said. “We’re training people to become solar installers, but what you find is that as people progress through their careers, a lot of them do become contractors, a good number do end up starting their own businesses, while others go into the union.”

OgunBadejo said that GRID is also building a network of minority- and women-owned contractors who work on electric vehicle charging infrastructure, home energy storage, and heating systems. The goal is to support these small businesses and help them gain access to funding from the Inflation Reduction Act, so that in turn, they can hire graduates of GRID’s training program.

Several experts interviewed for this story stressed their belief that any workforce development program has to be tightly connected to the people already doing this work—the contractors.

“The successful programs are tied directly to employer needs,” said Laure-Jeanne Davignon, the vice president for workforce development at the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, a clean energy policy nonprofit. “They have a direct line of communication to employers from the design of the program up through job placement.”

The Inflation Reduction Act includes $200 million to states over the next decade to train contractors in energy efficiency upgrades and electrification. Bartholomy, from the Building Decarbonization Coalition, said some of that money could go toward paying a portion of a trainee’s wages, enabling contractors like Borin to take on more trainees. (Some states also offer tax credits to employers who bring on apprentices, but California isn’t one of them.)

One challenge with involving contractors, though, is that many of them aren’t convinced of the benefits of switching to electric appliances. Take heat pumps. They transfer heat from the outside air indoors, even on very cold days, to provide space heating, and work in reverse to provide cooling in the summertime. They’re more expensive than a gas furnace up front but can pay off with savings in the long run. Even so, homeowners recount encounters with contractors who tried to persuade them out of buying electric heat pumps, raising doubts with customers about the higher price and whether they work as well as natural gas systems.

California is trying to change contractors’ minds through a $120 million initiative called TECH Clean California. A big part of it involves training contractors how to install electric heat pumps and water heaters but it also lays out available rebates and other subsidies that would help sell them to customers. The program launched in the middle of 2021, and so far, more than 600 contractors have participated, according to Evan Kamei, a program manager at TECH. Kamei said the initiative is also working to increase cooperation between existing training providers, like community colleges, utilities, and manufacturers.

While education, training opportunities, funding, and stronger collaboration between the networks of companies, schools, and contractors could all help ensure that people interested in becoming electricians get a shot at making it into the field, they still don’t necessarily address one of the biggest obstacles to “electrifying everything”—getting people interested in the trade in the first place. So how can the United States inspire more people like David Pitts and Borin Reyes?

“I think one of the big questions is really, do millennials and Zoomers see a career for themselves in crawl spaces and attics doing this work?” said Bartholomy. “You know, it’s, ‘You should be going to four year college and learning C++ programming, not working in the trades.’“

Asked if he had any ideas for how to get more young people interested in the field, Reyes didn’t skip a beat. “Showing them how much money they can make. That is the key.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the mean annual wage for an electrician in the U.S. is about $63,000 compared with an average of $58,000 for all occupations. But there’s a big range. In the Bay Area, the top-paying metropolitan area for electricians in the country, the average is $93,900, with many contractors topping six figures.

Another step is to raise awareness. Davignon’s organization, the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, recently won a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to develop an outreach campaign to advertise careers in renovating houses to be more energy efficient, known as “weatherization.” She said she hopes to raise more money to promote other jobs in clean energy, like electricians. One idea is a twist on the classic U.S. Army recruitment ad along the lines of: Your country needs you to be an energy hero.

“That’s the kind of thing we really need to start to remove the stigma from these trade jobs,” Davignon said. “You know, is the construction job sexy enough for someone or do they also want to be saving the world?”

NEXT STORY: What Keeps Public Employees In Their Jobs? It’s Not Just Pay