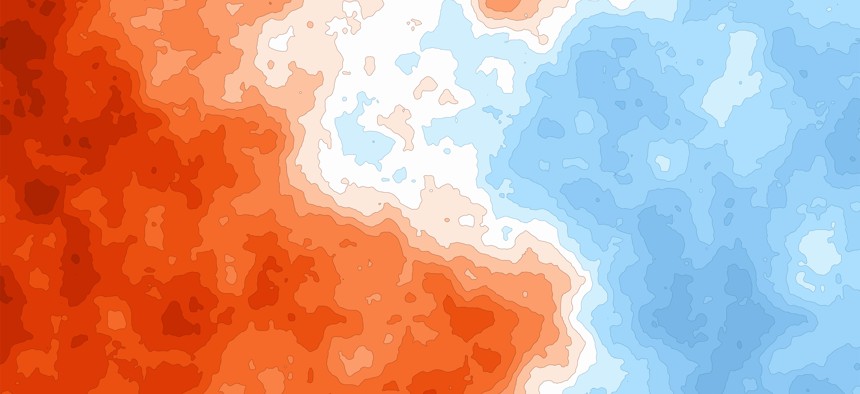

Urban heat map reveals priority spots for cooling efforts

FrankRamspott/Getty Images

Citizen scientists in Milwaukee collected air temperature and humidity data to help state officials focus where heat prevention efforts are most needed.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources collected temperature and humidity data in Milwaukee last summer to identify heat-sensitive areas so officials can prioritize placement of heat mitigating resources and services.

Using environmental and land cover data from the heat mapping campaign, DNR developed a public-facing map, the agency said in a Jan. 26 announcement. Users can filter layers by time of day—morning, afternoon and evening—and view temperature levels down to the street level.

“We wanted to know particularly where it was extra hot, and those might be places where we prioritize where we plant trees in the future,” Dan Buckler, DNR’s urban forest assessment specialist, said. Other measures include mapping out where to put cooling centers and emergency response services.

“We’re approaching this topic as a matter of public health because … high heat events have pretty significant health impacts,” he said. Heat has been a leading weather-related cause of death for decades, according to the National Weather Service, outranking natural disasters such as hurricanes, tornadoes and flooding.

To get the data, a team of volunteers including city staff, partnering organizations and community members took to the streets of Milkwaukee with car-mounted sensors. The citizen scientists were tasked with following nine designated routes so the sensors could collect temperature and humidity data every second for an hour, Buckler said. In areas that cars could not access such as parks, machine learning was used to create area-wide predictions.

The mobile sensors were provided by CAPA Strategies, an organization that provides data analytics and decision support to communities, through funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Analysts at CAPA Strategies also scrubbed the information to clear out unusable data, such as when volunteers drove too fast resulting in measurements that could not be calibrated properly.

Using cars to collect data was more efficient and reduced time and financial costs that other methods such as stationary sensors would likely incur. “Establishing [stationary] sensors … is much more of a massive undertaking,” Buckler said, as it’s an expensive process and requires more individuals with expertise.

It may also be time consuming to revisit sensor sites to manually gather data, he said, and cities may spend months or even years building out a sensor network that adequately covers an entire metropolitan area.

Results from the campaign were largely unsurprising, Buckler said. A project report showed residential areas with a high percent canopy cover retained less heat throughout the day while commercial locations with large amounts of asphalt often produced concentrated heat pockets.

However, combining this information with other data will give officials a more holistic view of their communities to better inform environmental decisions. For instance, officials should also consider where vulnerable populations are located, if current infrastructure enables the installation of trees or other structures to provide shade or whether there are heat-absorbing surfaces that can be painted a light color to reduce temperatures, Buckler said.

“[Heat] data is just one little piece,” he said.

The Milwaukee Sewerage District and Groundwork Milwaukee were also partners in the campaign. DNR’s effort is part of NOAA’s nationwide heat mapping campaign, which has operated since 2017. The program aims to help local officials understand how heat is distributed in their communities to improve sustainability plans, public health practices and other activities.

NEXT STORY: How AI helps one city spot damaged rooftops