NOAA aquatic bots break the ice on climate research

Connecting state and local government leaders

Over the years, NOAA has sent various data-taking probes deep into the Arctic Ocean looking for answers about climate change. In this latest, extreme test of technology endurance, the agency's swimming robots deliver high science at low cost.

The Apollo 17 crew reported that from space, Earth looks like a big blue marble. But ironically, we know very little about the vast and diverse oceans that make our planet blue.

“The ocean is a tremendous resource, yet we don’t understand it enough, how to get more food from it, the effects of it absorbing more carbon, or what will happen as it becomes more acidic,” said Christian Meinig, the director of NOAA’s Pacific Marie Environmental Laboratory. “In some ways we know more about deep space than our own oceans.”

Nowhere is that more true than in the Arctic Ocean. It’s a harsh place by any standard, and any explorer faces many obstacles. Much of the year it’s snowed over. The seas are unusually calm, but clouds block out the sky more than half the time. Its sea floor is ringed by pingos, mountains of sunken rock and ice that form and move over time. Like hidden underwater teeth, they can rip out the bottom of unprepared and unfortified vessels. Temperatures are also below freezing most of the time.

Over the years, NOAA has sent various data-taking probes into this netherworld because the Arctic Ocean has become invaluable when looking for answers about climate change. Recording temperatures, especially in columns of water going down six meters below the surface, could help scientists predict future key climate changes. Data could be shared with NOAA’s Fisheries Service, for example, to create smarter seafood management plans.

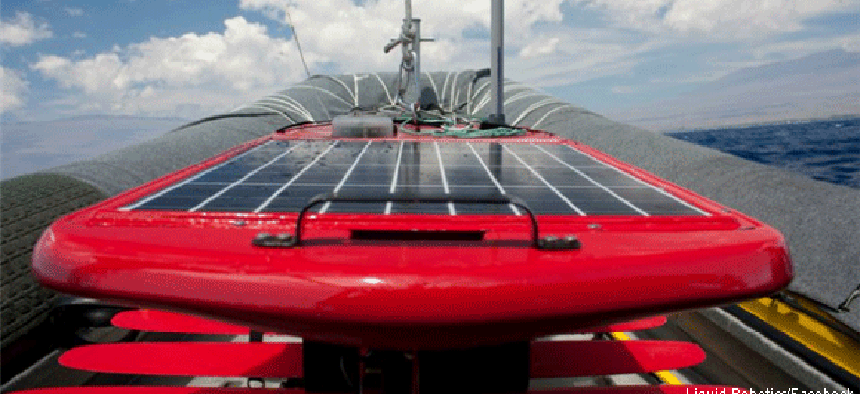

NOAA’s Meinig thought robots might handle these data collection tasks capably -- and relatively inexpensively, so he enlisted Liquid Robotics Inc., of Sunnyvale Calif., to help. A set of the company’s Wave Glider robots are currently swimming off the coasts of California and Hawaii.

According to Liquid Robotics senior vice president for product management Graham Hine, Wave Gliders are perfect for unmanned exploration because they are propelled by wave power. As a consequence, “they can operate for months at a time, never need to stop for refueling and are robust enough to survive in tough conditions,” he said.

Wave Gliders have proven to be surprisingly robust in the field for day-to-day operations, but for the Arctic mission, extreme cold was the enemy. Batteries don’t perform as well in cold environments, and the 90 percent cloud cover could limit charging the solar panels that power the instruments. “We added a supplemental lithium-ion battery pack with a 1,200-watt-hour capacity into one of the bays,” Meinig explained. “If the Wave Glider couldn’t charge, the extra batteries had enough power to run the instruments for 15 days.”

For scientific readings, six Therm¬Array thermistors from RTS Instruments of Maple Ridge, Canada, were molded into the tether that connects the float with the submarine, to record temperature at various depths.

Meinig explained that this first mission with the robots was half science and half proof of concept. “Our focus is how we best provide high-quality, low-cost ocean observing systems for research and operations,” Meinig said. “We’re constantly working towards that goal.”

On the low-cost side of the equation, NOAA rented a small boat and sent only two employees to launch the Wave Gliders at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. The same team was tasked to retrieve the boats at the end of their two-month journey.

For the scientific part of the mission, the robots followed each other at 12-hour intervals. So if one robot took readings at noon, the second would take the same sample at midnight. This allowed study of diurnal heating effects. “We held one on station to see if it could stay in place, while the second swam away,” Meinig said. “They both performed well overall.” They stayed in the Arctic for two months. Between them, they took over 900,000 temperature readings, the most ever in a survey of that part of the world.

Even though this mission only recorded temperature and telemetry, Meinig said there were many other factors that could be recorded by different instruments using the Wave Gliders. “We certainly plan on doing more with them now that we know we have an unmanned vehicle that can be launched and later recovered inexpensively by two people in a small boat,” he said.

That’s a big achievement for a robot that began as a tiny model floating in a fish tank at Liquid Robotics headquarters in California. Today it is swimming the world’s oceans from the Pacific to the Arctic, operating at lower costs to the public and taking hard-to-get readings that one day might help preserve the planet.

NEXT STORY: Is Windows 8's start-up too fast?