Government runs on a 64-year-old language. Could AI help change that?

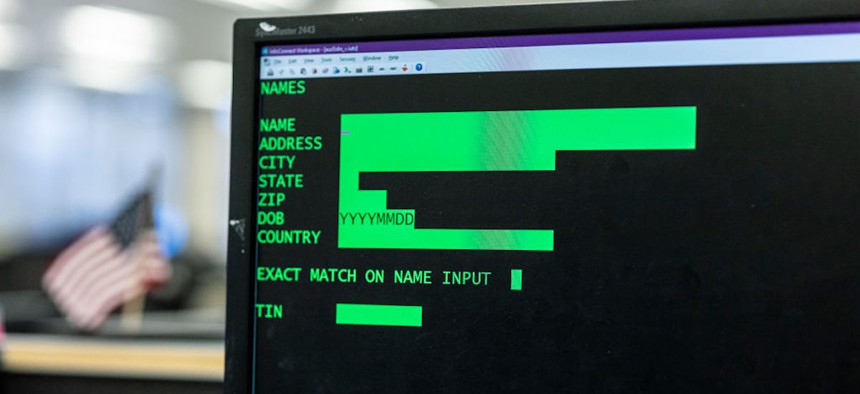

A computer running COBOL 73, an antiquated programming language, awaits taxpayer information entries at the Internal Revenue Service in Austin, Texas, on June 10, 2022. Matthew Busch for The Washington Post via Getty Images

COBOL is still relied on for many essential services. But as experts in the language retire, states are looking at new technologies and ways to change workplace culture to help ease the transition away from it.

As the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated in early 2020 and as governments moved much of their services online, one state put out an unusual call: It was looking for experts in a 60-year-old computer programming language.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy said in early April of that year that the state needed volunteers familiar with common business-oriented language, or COBOL, as many of the state’s vital systems like unemployment insurance relied on it to keep its mainframe technology functioning. As millions of laid-off workers flooded the state’s systems to file claims, the decades-old technology struggled to keep up.

“We have systems that are 40 years-plus old, and there’ll be lots of postmortems,” Murphy said during a press conference at the time. “And one of them on our list will be how did we get here where we literally needed COBOL programmers?”

A couple of days later at another briefing, Murphy reported that plenty of volunteers had “raised their hands.” He said he had even been called the "COBOL King," but New Jersey was far from the only government dealing with outdated, COBOL-dependent technology.

Myriad states faced similar issues during the pandemic, including Kansas and Connecticut. At the time, Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly lamented that the disease halted the state’s technology modernization process and kept Kansas on “really old stuff.” Some estimates have suggested that 45 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia still run COBOL, in addition to numerous federal agencies.

Today, COBOL is taught at only a handful of U.S. universities. The coding language is 64 years old—first developed in 1959 to process transactions in banking, retail, transportation and government programs like tax processing, Social Security and unemployment insurance. COBOL has given way to other languages and applications, and there is less of a pipeline of new COBOL talent coming through.

That is despite the language’s inherent importance. A global study conducted last year by enterprise software firm Micro Focus found that 800 billion lines of the code run daily in production systems, with more than half of survey respondents expecting to keep running COBOL applications for at least the next decade.

If COBOL applications stopped running tomorrow, the consequences would be “pretty darn bad,” said Frank Attaie, general manager for IBM’s U.S. public sector market.

While the pandemic shined a light on the language’s prevalence, states’ continued reliance on COBOL presents challenges for IT leaders who must balance the desire for modernization with a need to ensure their systems stay functional.

And the biggest challenge state and local governments face when maintaining these systems—as New Jersey and others found during the pandemic—is the lack of available workers with COBOL knowledge. Many have retired, or are retiring on “literally a daily basis,” Attaie said.

Maryland IT Secretary Katie Savage said in a previous interview that those retirements create a “significant operating risk,” especially if many of the people leaving are attached to the COBOL system and there is no obvious succession plan.

“For me, we're making the business case around why from a security and workforce development perspective, we have to upgrade,” Savage said at the Google Public Sector Forum last month.

It can be heavy going, however, as those still working in state IT departments may be reluctant to use newer tools.

“Lots of folks are tied to the mainframe; they’re civil servants that have worked in our agency for a long time,” Amy Pechacek, Wisconsin’s secretary of workforce development, said at the forum. “They're wonderful team members, but they are very used to how things have always been, and they're used to moving at the speed of government, which means historically, very slow.”

Getting employees on board to transition away from COBOL is crucial, therefore. Pechacek said it has been important for Wisconsin to take an “iterative approach” to modernization, rather than changing too many systems too quickly and risking outages. Whether it be clearing a backlog of unemployment insurance claims, or looking to artificial intelligence-driven chatbots, Pechacek said those wins help “move the needle in terms of cultural acceptance.”

Savage said she and her fellow IT leaders in Maryland have held town halls with employees to hear their concerns and to ensure that staff are familiar with the overall vision. She said she was “blown away” by the desire among IT staff to learn new skills to meet that vision.

The transition away from COBOL will take time though, and some believe AI could be a solution. IBM recently unveiled a generative AI tool to help developers produce code more quickly and also help facilitate faster translation of COBOL to Java, which many see as a successor language.

Ultimately, AI could help governments retire COBOL. But instead of starting from scratch, governments would be able to transition their existing data and records. It means, said Attaie, governments can have a “more modern footprint without losing all of the resiliency, the availability, the code base and data” that has already been accumulated.