Revisiting a 50-Year Old Economic Development Tool

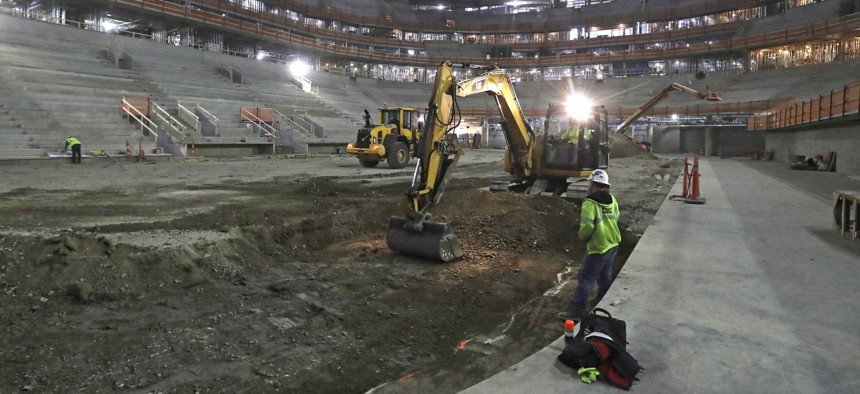

In this Jan. 3, 2017, file photo, workers begin excavation for an arena in Detroit that tax increment financing was used to help develop. AP Photo/Carlos Osorio, File

Connecting state and local government leaders

New research offers a fresh look at tax increment financing.

David Merriman says back when he began researching tax increment financing districts he was somewhat skeptical of the widely used economic development tool.

“I thought, ‘They’re a terrible idea, they’re like kind of a gimmick,’” recounted Merriman, a professor in the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who has written papers on the topic dating back about two decades.

But over time Merriman’s views have evolved. “Even with all its flaws, I kind of am more positive towards them,” he said by phone on Tuesday. “It’s hard to make it work. But I do think that they have a useful role and I wouldn’t get rid of them. I’d keep them.”

The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy this week published a report that Merriman authored about tax increment financing, or TIF, districts.

It outlines how tax increment financing works, along with some of the potential benefits and pitfalls. The report notes that even though tax increment financing has been around for over 50 years, it still tends to be poorly understood at times and its effectiveness is disputed.

Merriman explained that previous statistical research illustrates how tax increment financing has an imperfect track record. “Not in all, but in many cases, TIF doesn’t do much to stimulate economic development beyond what would have happened anyway,” he said.

“It’s not a magic wand,” Merriman added. “And it may be kind of more useful in terms of redirecting economic development towards particular neighborhoods.”

TIF comes in different flavors. But the basic idea is a local government designates a special district, with defined boundaries. After that, increases in property tax revenue from real estate development in the district are reinvested to support economic growth there over a set amount of time.

The term “increment” refers to gains in property tax revenue that result from new real estate development in the district, above a baseline level of growth expected without the TIF.

State legislation generally sets specific guidelines for how tax increment financing works in different places. But an important concept is that it’s often intended to incentivize development that would not have happened “but for,” or absent, the tax financing district getting established.

Tax increment financing proceeds can be used in a number of ways. For instance, improving roads, or extending power or broadband infrastructure, or subsidizing eligible developer costs. A Montana program mentioned in the report features a revolving loan program.

“TIF is neither a property tax break nor an increase,” Merriman writes. “TIF is a method for financing public expenditures that may then promote economic development.”

The report goes on to point out that a potential benefit from TIF arrangements are commitments between local governments and private entities that might not otherwise be possible.

A government might be eager for a developer to make a private investment in an area to increase the tax base there and to boost the local economy. But the developer may be reluctant to do so without certain infrastructure upgrades.

Tax increment financing provides a possible path forward, allowing the government to say they'll invest the property tax gains from the new development into the desired infrastructure.

In some cases, governments may issue bonds to be repaid with expected TIF revenues.

“TIF is appropriate when you need both the private sector and the public sector to work together over a long period of time to do some kind of development,” Merriman said.

But there are also risks with tax increment financing that the report gets into as well.

For example, a city might use it as a method to divert and capture new tax revenue that would have otherwise flowed to overlapping governments, like school districts or counties. “But for” provisions in state laws are meant to safeguard against this sort of activity.

These provision can be subject to a wide range of interpretations though. “Given the variety of interpretations available, it is difficult to imagine a development that would not meet the ‘but for’ test in some sense,” says an audit report from Minnesota that Merriman cites.

Transparency is another concern, one underscored by TIF activity that has taken place in Chicago over the years. The city, Merriman’s report says, has used tax increment financing more than any big city in the U.S. and had 149 TIF districts as of 2017.

In contrast, San Antonio, Texas had 19 of the districts and Dallas had 18.

Merriman outlines how there have been past controversies in Chicago that center on who decides how TIF tax dollars are used and how the revenues are tracked and reported.

Reporting by the Chicago Reader raised questions about whether Richard M. Daley, who served as mayor from 1989 to 2011 used TIF dollars as a “shadow budget.”

Since then, the city has taken steps under Mayor Rahm Emanuel to improve transparency. But it has not implemented all of the recommendations outlined by a special TIF reform task force.

The report notes that Chicago is not unique in this regard, and that the possibility exists elsewhere for TIF revenues to be used as a “slush fund” of sorts, or that the money could go to cover expenses and subsidies without an adequate accounting of the results.

“TIF can be used appropriately,” Merriman said. “But we need to keep on it.”

A full copy of the report can be found here.

Bill Lucia is a Senior Reporter for Government Executive's Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Prepping for a Hurricane That Could Stay for Days