How a different kind of drug testing can help communities stave off overdoses

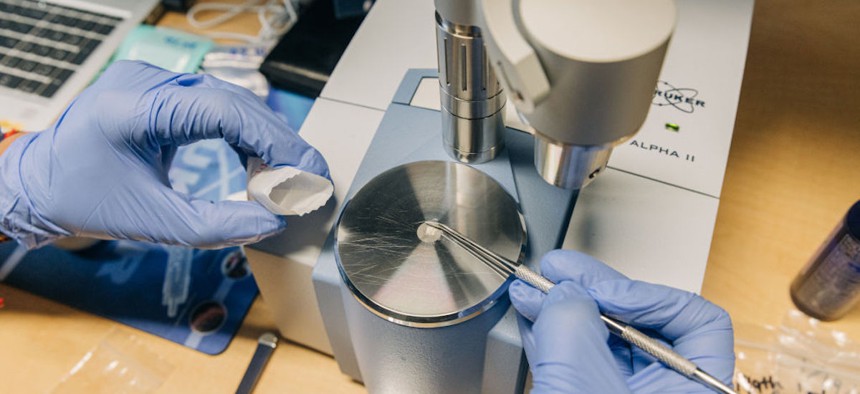

Drug-check technician Yarelix Estrada puts substances on an infrared spectrometer device at the overdose prevention center OnPoint NYC in New York City on Jan. 23, 2023. Jeenah Moon for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Insights from advanced drug-testing services are proving essential for public health officials struggling to contain an evolving crisis.

Opioid’s decadeslong grip on the nation continues to tighten, despite a nearly 50% reduction in prescription opioids since 2012, a new report finds. In fact, a steady increase of opioid-related fatalities in recent years suggests “overdose epidemic is deadlier than ever,” with overdose deaths estimated to surpass 109,000 last year.

Opioids like morphine, oxycodone and legally manufactured fentanyl originated as a pain management medication, said Bobby Mukkamala, chair of the substance use and pain task force at the American Medical Association. But when the burgeoning addiction epidemic forced health care providers to limit opioid prescriptions, illegally produced versions of the drugs made their way to the streets.

“Now you’ve got people that have pain that are looking for a way to treat that pain, and the only option is something outside of the clinical space, which now means illicit drug use,” he said. What makes matters worse, he said, is that criminally manufactured fentanyl, which is contaminating many street drugs, is “highly unpredictable and highly fatal,” unlike pharmaceutical opioids.

In the report released earlier this month, the American Medical Association highlights the need for more aggressive harm reduction strategies from governments at all levels to address the ongoing opioid crisis.

One way state and local governments are expanding harm reduction measures is through drug-checking services, which identify the content and potency of a user’s supply. Essentially, Mukkamala said, a test can help a user determine, “Does this [drug] have the potential to kill me?”

Insights from drug-testing services are also essential for public health officials and policymakers struggling to contain the crisis.

“It’s critically important to know what people are using, because it’s not a stationary target,” Mukkamala said. If there were just one drug to worry about, for instance, it’d be a lot simpler to manage. But the reality is, he said, the evolution from prescription opioids to illicit fentanyl, then to rainbow fentanyl and now to xylazine, indicates that the opioid crisis is outpacing governments’ ability to solve it.

Drug-testing, however, can alert officials of new drug threats in a community and inform treatment and management decisions. For instance, more state and local governments are increasing access to naloxone, Mukkamala said, but drug-testing data shows xylazine, a sedative used in veterinary practices, is appearing in local supplies more frequently. Since naloxone is ineffective against xylazine, he said, then officials must consider alternative overdose medications.

Across the country, more than half of states have passed laws since 2018 to expand access to fentanyl test strips, or paper strips users dip in water that’s been mixed with the substance they’re testing to detect the presence of the fatal synthetic opioid.

The latest state to take action is New York. Gov. Kathy Hochul signed a bill Nov. 19 that allows health care providers and pharmacies to distribute “drug adulterant testing supplies” to identify the presence of fentanyl in drugs. Increased access to test strips can let individuals know whether fentanyl has been detected and protect them from consuming a fatal dose, but strips can’t determine the amount of fentanyl present.

That’s why the New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Health, or DOHMH, has supported drug-testing services at four needle exchange service sites since 2021. At the facilities, people can submit their drugs for testing to check if there are any lethal substances present.

The nonprofit OnPoint NYC operates an overdose prevention center where drug-checking is gaining traction as a harm reduction strategy. The facility, which is partially funded by DOHMH, uses infrared spectrometry to reveal the chemical makeup of substances, such as fentanyl concentrations.

Preliminary drug data from 2022 showed that fentanyl made up as much as 20% of some drug samples, indicating “high concentrations of fentanyl in some drugs sold such as heroin,” officials reported. Data also showed a growing presence of xylazine, which contributed to 19% of opioid-involved overdose deaths in 2021.

“By knowing what substances are in their drugs, individuals can make a more informed choice and reduce overdose risk,” DOHMN told Route Fifty in an emailed statement. And according to OnPoint NYC drug-checking program data, participants have reported that drug test results influenced them to reduce how often they use drugs.

While fentanyl testing strips are now legal in most states, drug-checking services have not been widely authorized, with a few exceptions. Earlier this year, Vermont passed a bill to approve $700,000 in funds from opioid settlements to support drug-checking service providers in the state. Minnesota Gov. Tim Waltz also signed legislation in May to decriminalize drug paraphernalia, including drug-checking equipment that can be used at syringe service providers, for instance, to detect fentanyl in substances.

Harm reduction organizations that offer drug-checking services should serve as the first step to recovery, Mukkamala said, because they can deliver an “intersection of services” for community members and provide an opportunity to treat people before they’re in the emergency room. But effective treatment and prevention of the nation’s opioid crisis depends on officials “being aware of what’s around the corner, and what’s on the street right now.”